Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, New South Wales

Part of a small group tour of World heritage sites on Victoria, NSW & South Australia for mature and senior travellers. Learn and explore in the Mungo National park about Aboriginal settlement and the fauna and flora of this National park.

19 Jan 21 · 10 mins read

Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, New South Wales

In the remote desert of Western New South Wales, scientists in the late 1960s and early 1970s made some of the most important archaeological discoveries ever found in Australia: the remains of an Aboriginal Australian, a woman was found by geologist Jim Bowler and then some year later, a man was discovered. Known as Mungo Lady and Mungo Man, they are among the oldest ancestral remains of modern humans, homo erectus in the world, and are possibly Australia‘s oldest human remains to date.

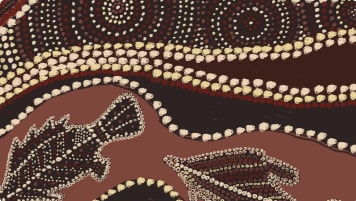

While most Australians are familiar with this story, few know much about the place they were found: the extraordinary Mungo National Park, in the Willandra Lakes Region World Heritage Area of Western New South Wales. Few places in Australia feel as ancient as this remote corner of south-west NSW, a place where geology and history combine, where an aboriginal person hunted megafauna beside vast outback lakes. Visit and marvel at the remains of ancient megafauna and this incredibly long Aboriginal history, in a place of stunning natural beauty.

Geology and history of the Willandra Lakes:

The Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area spans 2400 square kilometres of semi-arid salt bush plains, dunes, and sparse woodlands in the Murray River Basin of south-western NSW. It consists of 19 dry relict lakes, that were once filled with glacial waters flowing east with meltwater from the Great Dividing Range. These lakes were full from around 150,000 years ago to around 50, 000 years ago, when the end of the Ice Age meant that glacial ice diminished and water no longer flowed from the highlands. The last lake dried up 17, 500 years ago.

The lake floors and dune systems that surrounded them remain distinct today. Each lake has crescent-moon shaped dunes, known as lunettes, on their eastern sides, formed by the prevailing westerly wind. Most iconic is Lake Mungo’s striking Walls of China, part of a 26-kilometre long lunette. The particular forms of the Walls of China were formed thanks to erosion in the 19th and early 20th centuries, as settlers allowed up to 50, 000 sheep and even more rabbits to destroy vegetation on the dunes, causing them to erode more quickly.

The first indigenous Australian people are likely to have arrived in Mungo National Park around 60, 000 years ago, at the front of a wave of migration that carried small bands of Aboriginal Australian travellers from Africa, along the coasts of Asia, and over an ocean crossing from Indonesia to Australia, much shorter than today thanks to lower sea levels.

The first occupation sites in Australia are likely under the sea level today, meaning that we are now unlikely to find traces of them. The earliest evidence found is the Malakunanja Rock Shelter, 50 kilometres from the Arnhem Land coast, though dating of indigenous Australian settlement is back as far 85,000 -120,000 years ago.

The next evidence we have of settlement in Australian history comes from Mungo National Park. Geological layers dated as far back as 50, 000 years have uncovered stone tools and hearths, shellfish middens, and butchered animal bones. This is long before the modern human reached Western Europe.

Early Aboriginal australian inhabitants of the area – including Mungo Man and Mungo Lady – would have lived in a fertile environment, in which lake water supported an ecosystem of golden perch, Murray cod, yabbies, shellfish and mussels. Reed beds and eucalyptus by the side of the lake attracted waterbirds, amphibians, mammals and reptiles. The Indigenous Australian people of the Willandra Lakes region area also hunted for emus, kangaroos, and other large species.

Ancient Aboriginal people also hunted and consumed ancient Australian megafauna. A range of megafauna fossils have been found in the lunettes, including:

- Procoptodon goliah: This ‘short-faced’ kangaroo was the largest known kangaroo, measuring more than 2 metres in height and 200 kilograms in weight. It had long arms and claws for reaching vegetation in trees. It survived in Australia until 30, 000 years ago.

- Genyornis newtoni: A giant flightless ‘thunderbird’, common until 45, 000 years ago. Measuring 2 metres in height and over 240 kg, this bird has often been mistaken for a relative of the emu, but is in actuality a giant duck or goose. Pieces of egg-shell are commonly found at Willandra.

- Zygomaturus: This semi-aquatic, hippo-like mammal is an ancestor of the modern wombat. It likely lived around the banks of the lakes, eating aquatic vegetables.

However, as the lakes began to erode, life changed. Around 35, 000 years ago, the water became slightly lower, and the first dunes of the lake mungo lunette were formed. The megafauna were gone, though life was still abundant.

20, 000 years ago, the climate had changed considerably. The lakes were starting to dry, and people had to hunt and gather over large areas to survive. By 10, 000 years ago the lakes were no more, though people continued to live on the dunes, hunting seasonally.

Discovering Mungo Man and Mungo Lady:

In 1968, geologist Jim Bowler made a (almost by chance) discovery that would transform Australian history . A geologist by trade, rather than an archaeologist , he was interested in the park as evidence of Ice Age climate change. Few people had explored the now-dry ancient lake beds of the Willandra lakes region that spanned sheep stations, and geologist Dr Jim Bowler , mapping the area, came across skeletal remains emerging from an eroded dune around Lake Mungo. Bolger returned with archaeologists John Mulvaney and Rhys Jones, and – assisted by colleagues at the Australian National University – discovered that the remains were of a female human, representing some of the oldest human remains of an ancient people in the Willandra lake region of outback NSW on the Australian continent.

Further investigations revealed that ‘Mungo Lady’ – as she was now called – was a young woman. She had been ritually buried: cremated, then crushed, burned again and buried in the lunette.

In 1974, Bowler returned to the lake and found more remains – this time of Mungo Man. Investigations revealed that Mungo Man was around 50 – a good age for a hunter-gatherer – while his teeth indicated a diverse diet. Like Mungo Lady, he had been ritually buried, placed on his back, with hands crossed in his lap and his body decorated in red ochre and placed in a traditional ochre burial pit.

Eventually, the two skeletons were scientifically dated as being around 40, 000 to 42, 000 years old, though thanks to his knowledge of geological layers, Bowler already knew that they were the most ancient remains found in Australia found so far. Prior to the discovery, scientists believed that Aboriginal people had been in Australia between 15 and 20 thousand years. Mungo Lady and Mungo Man revealed a much more ancient history .

They are among the oldest human remains of Homo sapiens in the world, and among the earliest examples of ritual burial– indicating spirituality, cultural practice, and abstract thought. Given that ochre is not found naturally in the Willandra Lakes area, they also provide evidence of some form of trade occurring.

The discovery of the remains of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady proved to be a mixed blessing for their Aboriginal descendants – the Paakantji, Ngyiampaa, and Mutthi Mutthi. The discovery was made in a time of political ferment for Aboriginal groups across Australia, centred around the land rights movement. As Bowler recalls, Mungo Lady was discovered a year after the Indigenous people of Australia achieved citizenship by referendum in 1967, a time in which ‘Aboriginal people were being heard’ . For the Paakantji, Ngyiampaa, and Mutthi Mutthi, the discovery confirmed what they already knew – that they ‘were always here’ – and gave them a powerful claim to land rights. Moreover, the discoveries finally and permanently overthrew the psuedo-science of phrenology, devoted to proving that Aboriginal people were ‘primitive humans’.

Mungo Man Returns Home

Despite the benefits of the discovery for the claim to Indigenous rights, the removal of Mungo Man spurred an outcry from Aboriginal communities. The remains had been taken to Canberra for further study without consulting the traditional owners of the land; this led to divisions between the Australian government’s scientists and Aboriginal people continuing throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Scientists asserted the universal value of Mungo Man for science and national identity. They saw it as imperative that the skeleton be kept safe, as future developments in DNA research and improved X-ray tests might one day reveal new insights about the diet, life expectancy, health and cultural practices of early humans, or about mankind’s origins.

Aboriginal people, on the other hand, sought to protect their cultural heritage through the reparation of ancestral remains. They appealed for the return of human remains as a form of apology for Australia’s tragic colonial history. For them, this was also a matter of respect for their ancestors. Like many indigenous groups, the local tribes believe that a person’s spirit will be subject to wandering the earth endlessly if his remains are not buried in Country.

In 1989, the parties agreed to a conference at Lake Mungo, in which a compromise was met, in which both would respect the others interests in a collaborative approach. As a result, further human skeletal remains have remained in situ, and in 1992 ANU returned Mungo Lady to Lake Mungo and the traditional owners. Relations further improved from here as young Aboriginal people trained as rangers, archaeologists and heritage officials, and in 2007 the Paakantji, Ngyiampaa, and Mutthi Mutthi gained joint management of the parks.

The process of returning Aboriginal remains accelerated in 2002 after the Australian government recommended that repatriations be unconditional. Although this directive had no legal force behind it, Australian institutions responded with increased energy. A network of heritage officers began systematically connecting with Aboriginal communities all over Australia to empty museum collections

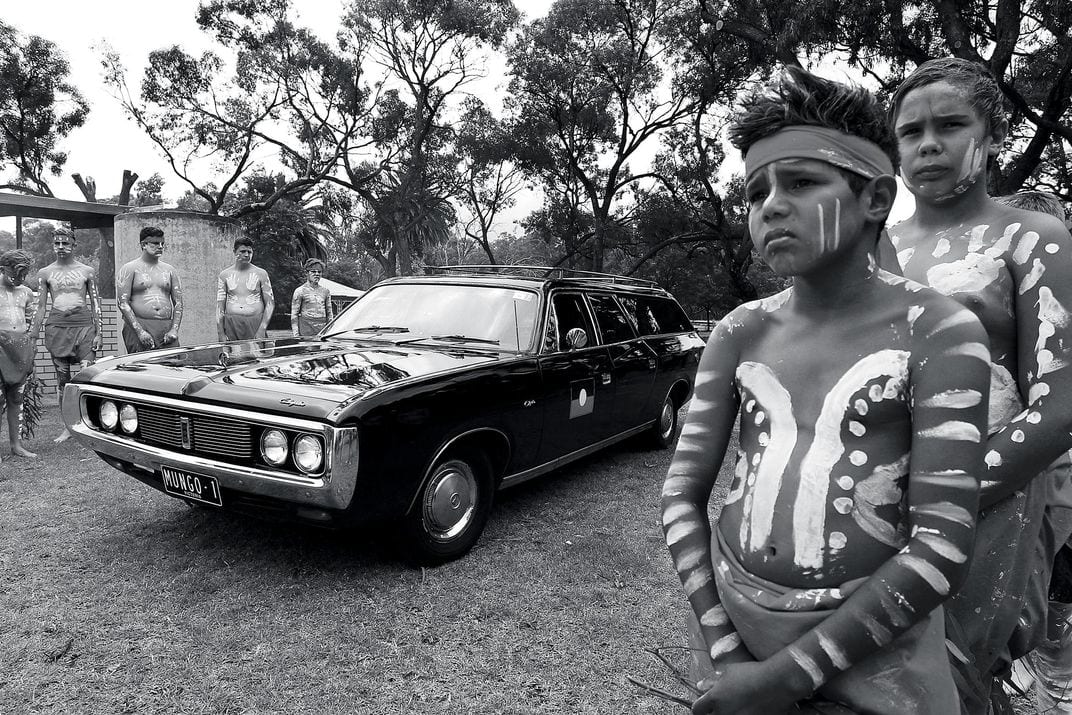

Tony Perrotet, writing in the Smithsonian Magazine, describes Mungo’s Man return as “the climax of this anti-colonial shift”. In November 2017, his hand-carved casket was transported in a black hearse across the Western NSW outback towards Lake Mungo, followed by a convoy of Aboriginal elders and activists. Along the way, the repatriation event was marked by a traditional purification ceremony led by an Aboriginal elder that involved cleansing the coffin with smoking eucalyptus leaves. At Lake Mungo his coffin was laid out and covered with leaves, finally returned to his descendants.

Today the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington D.C. looks after the collections made by the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948. This was a ten-month venture which gathered thousands of biological specimens and cultural items, which are still being studied today. The remains of over 40 Aboriginal individuals were for decades part of this collection but by 2010 the museum had returned the Arnhem Land remains on loan from the Australian government. The museum now works closely with Aboriginal groups to repatriate remains collected from other parts in Australia.

The Willandra Lakes today:

The discovery of Mungo Lady and Mungo Man paved the way for the Willandra Lakes to be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Area. In 1979, it was made a New South Wales National Park, and was added to the World Heritage List in 1981 – one of the first World Heritage sites in Australia – and one of only four in Australia (along with the Tasmanian Wilderness, Uluru, and Kakadu National Park) recognised for both their cultural and natural value.

Lake Mungo has proven a rich record of archaeological finds. Other human remains have been found in the area as well as middens (food waste), fireplaces, and stone tools. In 1987, ‘Mungo Child’ was discovered, likely of similar antiquity to Mungo Man. ‘Mungo Child’ is the only juvenile skeleton found in the 40,000 year range in the Asia-Pacific region. In accordance with the wishes of the park’s Aboriginal custodians, Mungo Child was never excavated, and subsequent human remains found in the park have been reburied and covered with shadecloth to prevent further erosion.

In 2003, a young Mutthi Mutthi woman, Mary Pappin Jnr., noticed footprints on the sand. These were investigated by archaeologists, and were revealed to be evidence of continued human occupation of around 20, 000 years old – among the oldest footprints in the world. Subsequent excavations found extensive prints, the largest collection of Ice Age prints in the world. One group of tracks reveals deep impressions left by large feet, likely a group of men in a hunting party. A grove reveals where a sphere left its target. Another group is likely a family, with a number of children from six to nine. The tracks reveal where one child wandered off, before being called back to the group.

Visitors generally reach Mungo National Park via Mildura or Balranald. Accommodation includes camping at the Main Camp and the more-remote Belah Camp, while just outside the camp is the Mungo Lodge.

Tour of Mungo National Park

Odyssey Traveller visits Mungo National Park as part of our tour of Southern Australia, including World Heritage sites and more. Designed to make you re-think the way you see Australia, our tour focuses on the borderlands between South Australia, Victoria, and New South Wales. Beginning in Adelaide city, our tour heads east to Port Fairy, before heading to the Budj Bim World Heritage Site, an important place of Aboriginal aquaculture. We then go on to Mildura and the mallee, touring the spectacular scenery of Mungo National Park on a day trip from Mildura, before heading to the outback city of Broken Hill. Finally, our tour takes us through South Australia‘s spectacular Flinders Ranges and to the mining town of Burra, before returning to Adelaide city.

Travellers with an interest in touring Australia may want to check out some of our other tours. Our guided tour of Adelaide and surrounds isn’t just an Adelaide city tour, but takes in the boutique wineries of the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale wine region, the historic Adelaide Hills and Fleurieu Peninsula, and the native wildlife – including the fur seals of Seal Bay – and remarkable rocks of Kangaroo Island. Our tour of the Eyre Peninsula, Yorke Peninsula and Gawler Ranges takes us to Port Lincoln, Australia‘s ‘seafood frontier’, for panoramic views of the Southern Ocean, and on to Baird Bay, where we see fur seals and Australian sea lions at their only mainland breeding ground. And our wildflowers tour of Western Australia takes in the incredible biodiversity of Australia‘s south-west, visiting stunning wildflowers in Esperance and Albany, and stopping in for a cellar door winery tour at the Margaret River, one of Australia‘s most celebrated wine regions.

Articles about Australia published by Odyssey Traveller:

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to New South Wales:

- UNESCO: Willandra Lakes Region

- Mungo National Park

- Mungo Lady and Mungo Man

- Defining Moments: Mungo Lady

- Finding Mungo Man: the moment Australia’s story suddenly changed

- Australian Dictionary of Biography: Mungo Lady

- Mungo Man: Australia’s oldest remains taken to ancestral home

- A 42,000-Year-Old Man Finally Goes Home

- OPINION: It’s time to honour Mungo Lady

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

Related Tours

days

Mar, May, Aug, Sep, Oct +2Small group tour of World Heritage sites and more in the Southern States of Australia

Visiting New South Wales, South Australia

Discover the World Heritage Sites of the southern states of Australia travelling in a small group tour. A journey of learning around the southern edges of the Murray Darling basin and up to the upper southern part of this complex river basin north of Mildura. We start and end in Adelaide, stopping in Broken Hill, Mungo National Park and other significant locations.

14 days

Mar, May, Jun, Jul, Aug +3Escorted small group tour of Western New South Wales

Visiting New South Wales

Discover the the Brewarrina fish traps, Aboriginal art at Mt Grenfell and visit the opal fields of White Cliffs. This small group also visits the World Heritage Site of Mungo man and lady stopping in Mungo National Park and other significant locations such as Broken Hill.

From A$9,250 AUD

View Tour