British Church Architecture Through the Years

British Churches Through the Years “How old is this church?” asks Mary-Ann Ochota in a chapter of her book, Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Francis Lincoln, 2016, p. 250). In this article, we…

28 Jun 19 · 10 mins read

British Churches Through the Years

“How old is this church?” asks Mary-Ann Ochota in a chapter of her book, Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Francis Lincoln, 2016, p. 250). In this article, we will look at British churches and their architecture and how it evolved during the era of Anglo-Saxons and the profound changes during and after the Norman Conquest. Knowing this history will help you spot era-specific features in churches and make an informed guess regarding a church’s age–short of asking a resident historian or architectural expert. We will also look at features of graveyards, which can be found next to churches. Ochota’s book will be a reference, as well as other resources which will be cited and linked throughout this piece.

Pre-Norman Period: Romans, Celts, Anglo-Saxons

When we study churches in Britain, we also study Christianity and its long history. In the 1st century AD, Christianity “was just one cult amongst many” (BBC, 2011) brought to Britain from polytheistic Rome, except that this new religion from the east required exclusive allegiance to one god. Its followers refused to sacrifice to Roman gods, and to the emperor. According to Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, “This was an insult to the gods and potentially endangered the empire which they deigned to protect. Furthermore, the Christian refusal to offer sacrifices to the emperor, a semi-divine monarch, had the whiff of both sacrilege and treason about it.”

This led to the persecution of its followers. Dr Lunn-Rockliffe said the persecution were sparked by turmoil as Romans looked for someone to blame for their troubles. Nero blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD and, according to historian Tacitus, had a number of them torn to death by dogs. Christian persecution was at a fever pitch during the reign of Diocletian in the 3rd century AD, which also coincided with a chaotic political crisis within the Roman Empire. (You can read more about the Roman Empire in our previous article here.) Christians were beheaded, fed to wild animals, or burned to death.

This changed with the conversion of Constantine to Christianity in 312 AD. The new Christian emperor (who, says Dr Lunn-Rockliffe, still included pagan customs in his religious practice) announced in the 313 Edict of Milan his–and the Roman Empire’s–acceptance of Christianity and the decriminalisation of the religion. In 380, the Edict of Theodosius announced that the Empire now recognised Christianity as the state religion.

Thus ended the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, but Christianity remained a minority faith in Britain in the 4th century. The Romans left in 410 AD and were replaced by new invaders, the Anglo-Saxons, who brought their own faith. The Germanic Anglo-Saxon pantheon shares similarities with the Scandinavian Viking pantheon, featuring gods like Woden (Odin, god of wisdom) and Thunor (Thor, god of thunder).

Britain was then cut off from Christian continental Europe. However, Christian missionary activity continued primarily in places where Anglo-Saxons did not settle, like Wales, Ireland, and Western Scotland. St Columba came from Ireland and established a monastic community on the Isle of Iona in 563 (Ochota, 2016, p. 252) and stamped a Celtic identity on Christianity by way of its austere church architecture. Early Celtic churches were usually just one long, narrow room with high walls (p. 252), as simple as the monastic lifestyle.

Things were a little different in the south of England. St Augustine came from Rome and arrived in Kent in 595 AD with a mission to convert the Anglo-Saxon pagans. He later founded a church in Canterbury. The churches that were eventually built in southern England took the Roman basilica as inspiration and were bigger and grander (p. 252) than their Celtic counterparts.

The word “basilica” now denotes a title of honour to church buildings, but in ancient Rome it was used to describe any large roofed public building: market, meeting halls, courthouses, etc. Later, it came to denote a specific form of this building, an open hall with side aisles and a raised platform at one or both ends. In pre-Christian Roman architecture, the basilica also featured an apse, or a semicircular recess in a wall, to contain the raised platform. In a temple it would hold the statue of a deity; in a judicial building it would contain the magistrate. This form was adopted by early Christians for their place of worship.

The “basilica” took over northern England as well following the Synod of Whitby, where the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria decided to follow Christianity as practised in Rome instead of the way it was practised by the Celtic missionaries on Iona. (For one, the two “Christianities” had different methods for determining Easter.)

The agrarian Anglo-Saxons did not have a stone building tradition, and so their churches were originally built from timber. This unfortunately meant most of these early wooden structures did not survive time and the elements. The remaining Anglo-Saxon timber church still standing is St Andrew’s Church in Greensted, Essex, with planks dating back to 1060 but with some older excavated structures found dating from the 6th and 7th centuries. It is still used for regular Sunday services.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Tim Heaton – geograph.org.uk/p/5943389

When the Anglo-Saxons started building using stone, they simply reused the bricks left behind by the Romans. One of the earliest stone churches built in England was St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury (597 AD) and was constructed in this manner. The largest stone Anglo-Saxon church in Britain is All Saints Church in Brixworth, Northamptonshire (circa 9th century).

Several Anglo-Saxon churches were built as towers (turriform churches), combining “ecclesiastical, residential, and defensive functions“.

Since Anglo-Saxons were not stone masons and in fact just reusing old materials, the cruder the masonry, the more likely it was the work of Anglo-Saxons (Ochota, 2016, p. 255). Their windows were usually triangular-headed with no glass and separated by a round pillar (baluster). Oddly enough, unlike their windows, Anglo-Saxons used round arches, which were not strong enough for load-bearing. You’d see additional structures (such as voussoirs, or arch stones) added through the years in order to strengthen the arch. You can see this in the south door of Brixworth Church, with the original Anglo-Saxon arch reinforced by a bigger, thicker Norman arch.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Stefan Czapski – geograph.org.uk/p/4708019

Norman or “Romanesque” Architecture

The Normans’ victory against the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings greatly changed life in Britain, primarily in England and much of Wales. For one, William the Conqueror claimed the land for himself and redistributed parcels to his own followers. (You can read more about it here.) They believed God was on their side, and built a church–called Battle Abbey–on their site of victory. The church was dedicated to the Trinity, the Virgin, and St Martin of Tours, and also served as a memorial to those who died in battle and as the Normans’ atonement for the bloodshed.

Their style of architecture was also called “Romanesque” as they derived inspiration from the Romans. Romanesque architecture developed simultaneously in the Normans’ native Normandy (now part of modern-day France) and England in the 11th to 12th centuries, with early buildings in both countries looking similar.

The Normans worked in stone and started building castles and replacing the Anglo-Saxon wooden churches with stone churches. They continued the Anglo-Saxon tradition of round arches and turriform churches, but as skilled masons, Norman walls were thicker, the nave (the room were the congregation gathered) wider, and the round arches stronger and decorated with patterns carved into the stone. They erected enormous load-bearing pillars within the churches and added carved stone fonts to hold water for baptisms. They added corbel tables below the eaves for extra support. Corbel tables are a continuous row of corbels, which are decorative architectural structures that projected from a wall and supported weight.

What is said to be a definitive example of the early Norman style is the Church of Saint-Étienne in Caen, Normandy (also known as Abbaye aux Hommes or “Men’s Abbey”), founded by William the Conqueror. Construction began around 1066-67. The English cathedrals of Ely (circa 1090), Norwich (circa 1096), and Peterborough (circa 1118) were modelled on this church.

Gothic Period

Around 1140, a new style of architecture emerged in northern France, initially called Opus Francigenum or “French Work” or “The French Style”, and which in the 16th century was derisively described by art critics as “Gothic”, referring to the “barbaric” Goths who they said destroyed the classical (and more tasteful) architecture of ancient Rome. It was this term of derision that we continue to use to this day, but stripped of the insult.

A main characteristic of Gothic design is the pointed arch, a design change from the rounded arch favoured by the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans. This shape is seen in Gothic windows and ceilings. The years 1160 to 1200 is also called the Transitional period, during which churches were built with a mix of the rounded Norman arch and the Gothic pointed arch (Ochota, 2016, p. 260). Durham Cathedral, constructed beginning 1093, features what is believed to be the world’s first structural pointed arch in its nave.

Church design in Britain increasingly became ornate as time passed and as the British adopted more of the elaborate style evolving in Europe. Thomas Rickman in his early 19th century book An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture (1817) divided medieval church architecture in England into three phases of Gothic (Ochota, 2016, p. 260):

- Early English Gothic (1200-1300)

- Decorated Gothic (1300-1400)

- Perpendicular Gothic (1400-1500 in London, but lasting into the 1600s in other parts of Britain)

To tell the difference between phases, you can look at the windows and buttresses (p. 263). Early English windows are also called “lancet” because they look like a lance, narrow and sharply pointed. Decorated Gothic windows are wider, less pointed, with, as the name suggests, decorative tracery. Also as the name suggests, Perpendicular Gothic windows have vertical tracery and framing, cutting the window into uniform panes.

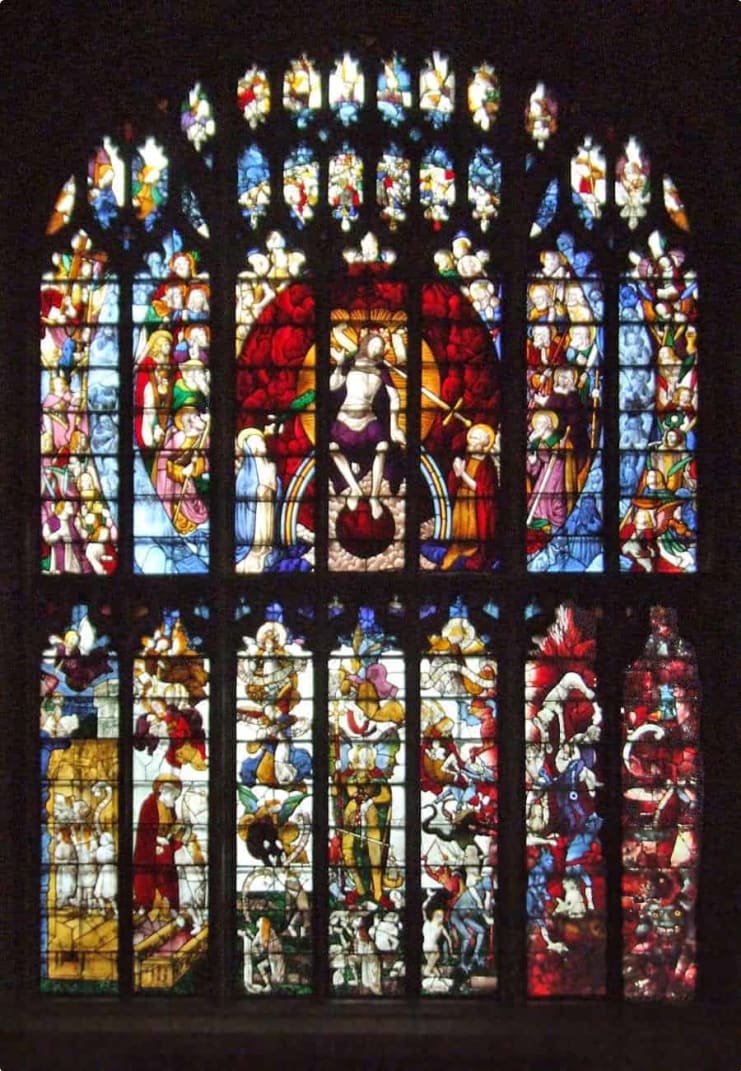

A notable church built in the Perpendicular style was St Mary’s Church in Fairford, Gloucestershire, England. It was rebuilt at the end of the 15th century by John Tame, a wealthy local wool merchant, and according to Robert Winder in his book The Last Wolf: The Hidden Springs of Englishness (Abacus, 2018) has “the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the country…the nearest thing in England to the Sistine Chapel” (p. 169). Fairford in the 16th century was home to a community of Flemish craftsmen, and St Mary’s stained glass was the work of a Flemish glazier, Barnard Flower (p. 170).

Norman buttresses, or structures of stone or brick built against a wall to strengthen or support it, were thick and shallow, but through the years they became slimmer and projected further from the walls, until churches sported “flying buttresses” starting around the 1400s.

These and other structural elements (spires, vaulted ceilings) allowed the British to build taller churches with thinner walls that were still structurally sound, and larger windows that would allow in more natural light. (Early Norman churches, with their smaller windows, would have been quite dark in comparison.)

The Gothic style made a comeback in the 19th century, the style called neo-Gothic or Victorian Gothic, using the more elaborate Perpendicular style or, as the Victoria & Albert Museum says, exaggerations of the Gothic’s key architectural elements.

Graveyards

In the introduction to his book, At Home: A Short History of Private Life (Doubleday, 2010), Bill Bryson mentions a friend, retired county archaeologist Brian Ayers, who tells him how country churches appear to be sinking–but only because the churchyard has risen from all the bodies buried there. As Ochota (2016, p. 270) confirms, “centuries of interments progressively raise the earth surface”. So the higher the graveyard, the older it is.

In Roman times, there were strict rules against having the necropolis (“city of the dead”) within the boundaries of a settlement throughout the empire, according to the United Kingdom’s Natural History Museum. This meant they had to be set up outside the city limits. Bodies were either cremated and the ashes interned in an urn, or buried with possessions that could help them in the afterlife.

The oldest example of an Anglo-Saxon Christian burial was unearthed in 2003 during roadworks in Prittlewell, near Southend, Essex. Found between a pub and an Aldi supermarket, the timber structure also housed rare and precious artefacts such as gold coins and gold-decorated drinking vessels, leading researchers to believe the burial must have belonged to an Anglo-Saxon prince. Gold-foil crosses were found at the head of the coffin, which means, according to the Museum of London Archeology, “the person buried can be identified with certainty as a Christian but he was also buried with funerary customs that reflect pre-Christian beliefs and traditions, including the burial mound, the chamber and the grave goods.” MOLA provides more information on their website about the excavation. In 2019, the chamber items were moved to the Southend Central Museum to be placed on permanent display.

In the Christian tradition, the bodies of the faithful had to be buried in the hallowed ground of the churchyard. This posed overcrowding problems during the Middle Ages, which led parishes to build charnel houses, or a vault to store human skeletons. As space is at a premium, bones would be exhumed from a grave and placed in the charnel house (that might be in or near the church) and the now-empty grave reused for the next burial.

Yew trees are found in Christian churchyards, but they have been planted since pre-Christian times. The yew was considered by native Britons to be a sacred tree and co-opted by Christians as a symbol of eternal life (Ochota, 2016, p. 272).

According to the National Churches Trust, graves in the churchyard face east–with the head to the west and the feet to the east–so the resurrected will face Jesus, who will be approaching from the east at the final Day of Judgement. Most burials traditionally took place on the south side of the church; the north side was seen as sinister (Ochota, 2016, p. 273) and used to bury unbaptised infants, criminals, or suicides. Priests, royals, and other people of equal standing were buried within the church; everyone else was buried outside in the churchyard.

Some English graveyards have lych-gates (from Old English lich=corpse) though most that survive date from Victorian times as medieval lych-gates were made of timber and had long since fallen. Lych-gates were where the corpse was brought and the priest approached to receive it for initial prayers, before moving on to the churchyard for the burial.

If you want to learn more, please read Mary-Ann Ochota’s Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Francis Lincoln, 2016), Bill Bryson’s At Home: A Short History of Private Life (Doubleday, 2010), and Robert Winder’s The Last Wolf: The Hidden Springs of Englishness (Abacus, 2018), as well as the many online resources linked throughout this piece.

You may also consider joining one of Odyssey Traveller’s many tours to the British Isles, such as the Villages of England tour, a 19-day fully escorted tour that will let you explore the history and culture of the British countryside; the Prehistoric Britain tour, which visits Skara Brae and other historic sites in Orkney, Shetland, and Wales; and the tour of the Scottish Isles which includes a stop in Iona. We specialise in small groups for senior travellers. Just click through to see each tour’s full itinerary and sign up!

For more information on all of our tours to the British Isles, click here.

Related Tours

19 days

Jun, SepEngland’s villages small group history tours for mature travellers

Visiting England

Guided tour of the villages of England. The tour leader manages local guides to share their knowledge to give an authentic experience across England. This trip includes the UNESCO World heritage site of Avebury as well as villages in Cornwall, Devon, Dartmoor the border of Wales and the Cotswolds.

From A$16,995 AUD

View Tour

13 days

AugExploring Wales on foot : small group walking tours for seniors

Visiting Wales

A Walking tour of Wales with spectacular views across as you walk the millennial path across the Irish sea or up in Snowdonia national park. This guided tour that provides insight into the history of each castle visited and breathtaking scenery enjoyed before exploring the capital of Wales, Cardiff with day tours of Wales from Cardiff. For seniors, couples or Solo interested in small groups.

From A$11,895 AUD

View Tour

20 days

May, Jul, Aug, SepScottish Islands and Shetland small group tours for seniors

Visiting Scotland

An escorted small group tour for couples and solo travellers of the Scottish isles including the isle of Skye draws on local guides to share their knowledge of the destinations in this unique part of Scotland. UNESCO world heritage site are visited as breathtaking scenery and authentic experiences are shared in a group of like minded people on this guided tour of remote Scotland.

From A$17,525 AUD

View Tour

18 days

Aug, Apr, SepSmall Group tours exploring the Treasures of Ireland

Visiting Ireland

An escorted small group tour to Northern Ireland & Ireland, with local guides and itineraries that give authentic experiences Ireland's capital, Dublin, including 1/2 day tour of St Patricks cathedral and Trinity college. Destinations also Aran islands , Kerry plus the world heritage site, the giant's causeway. Ireland tours for singles over 50 and couples.

From A$12,615 AUD

View Tour

From A$13,915 AUD

View Tour

20 days

May, Sep, JunWalking Ancient Britain

Visiting England

A walking tour of England & the border of Wales. Explore on foot UNESCO World Heritage sites, Neolithic, Bronze age and Roman landscapes and the occasional Norman castle on your journey. Your tour director and tour guide walk you through the Brecon beacons, the Cotswolds and Welsh borders on this small group tour.

From A$13,995 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Sep, JunRural Britain | Walking Small Group Tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A walking tour into England, Scotland and Wales provides small group journeys with breathtaking scenery to destinations such as Snowdonia national park , the UNESCO world heritage site Hadrians wall and the lake district. each day tour provides authentic experiences often off the beaten path from our local guides.

From A$15,880 AUD

View Tour

19 days

JulWhisky and Other Scottish Wonders

Visiting Scotland

A guided small group tour of Scotland is a day tour collection that includes Edinburgh, the royal mile, Edinburgh castle, and the old town a UNESCO World heritage site Experience and learn about, Kellie castle, St Andrews, Skye, Balmoral castle, Loch Lomond and Loch Ness as well touring the Scottish highlands to finish in Glasgow.

From A$18,395 AUD

View Tour

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$17,860 AUD

View Tour