Wedgwood Anti Slavery Medallion

Joshia Wedgwood a potter and entrpreneur who challenged society. The anti slavery medallion is an example of such challenges to society during the industrious revolution and consumer revolution in Britain. An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers.

13 Mar 24 · 9 mins read

Josiah Wedgwood Anti Slavery Medallion

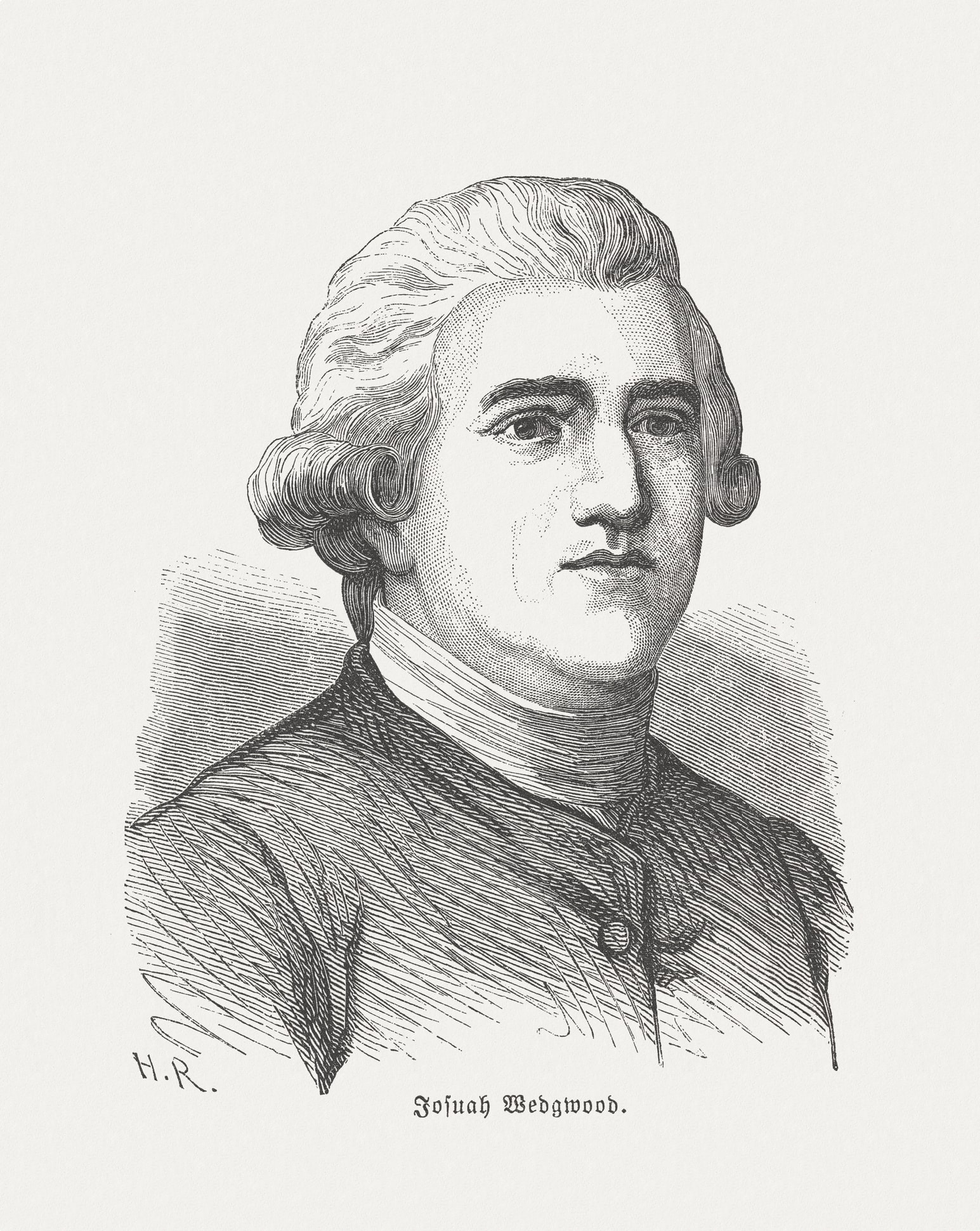

Throughout his life, the famed English entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood was deeply concerned with the social issues of his contemporary 18th century Great Britain. Unsurprisingly then, he was actively involved the cause for the abolition of slavery from 1787 until his death in 1795, serving as a committee member of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

His most lasting contribution to the movement was undoubtedly his anti-slavery medallion – an oval cameo depicting a chained African male. Distributed by the thousands, the fashionable medallion would evoke the sympathy of citizens across both the British world and America as a central piece of propaganda in the campaign to end the transatlantic slave trade. Indeed, it is widely regarded as the defining symbol of anti-slavery activism.

This article explores Josiah Wedgwood and his medallion’s role in the anti slavery movement of the late 18th century Britain. It is intended as background reading to Odyssey Traveller’s tours to Britain. Britain in the time of Wedgwood is explored on our tour focused on Victorian Britain, as well as our Agrarian and Industrial Britain Tour and our Canals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour. Just click the links to see the full itinerary and sign up!

For more information, readers are urged to take a look at Tristram Hunt’s book The Radical Potter: The Life and Times of Josiah Wedgwood, as well as Mary Guyatt’s journal article ‘The Wedgwood Slave Medallion’. Both were used extensively in the writing of this article.

The Anti-slavery Movement in 18th century Britain

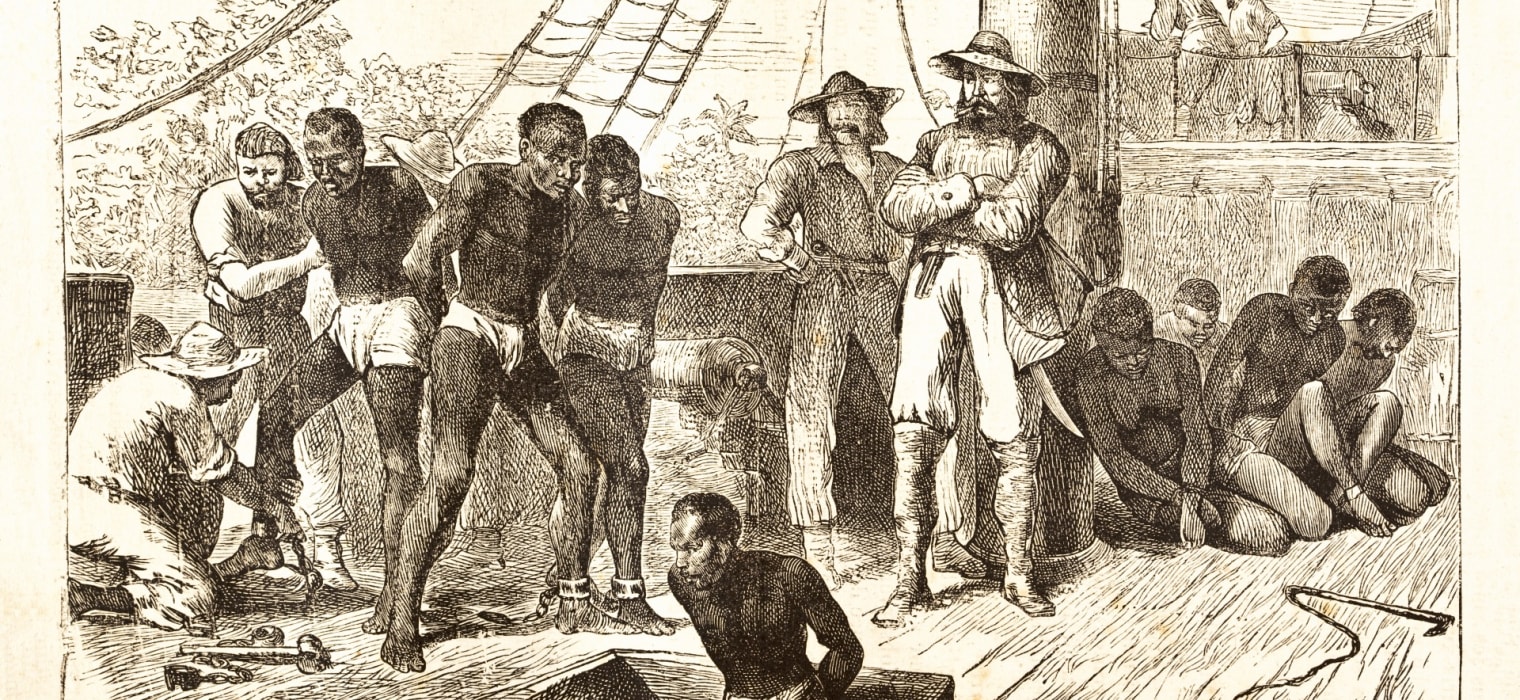

During the 18th-century, slavery was embedded in the consumer economy through its provision of sugar and cocoa, molasses, and cotton. Slave traders, slave owners, and the consuming public all benefitted, either financially or materially, from the exploitation of over 11 million African slaves.

Nowadays, the practice can only be regarded as obscene. But in those days, various arguments were put forward to justify its existence. These varied from theories espoused by plantation owners and slave traders that blacks were an entirely separate species, to the assumption that the British economy was dependent on colonial trade and the slave labour that that entailed. Both science and theology were used to support these views.

However, by the second half of the century, a vocal minority had begun to question the ethics of slavery. The impetus came in the theories of Enlightenment philosophers. They had begun to view man as a social being whose happiness ultimately depended on living in a thriving community, in which the liberty of all its members was upheld. Slavery was seen to violate the rights of man.

Although not all contemporaries had access to the writings of Enlightenment thinkers such as Montesquieu, Francis Hutcheson and Adam Smith, anti-slavery sentiment was also being expressed at the churches. Members of the non-conformist churches in particular – that is the Quakers, Baptists, Methodists, and Unitarian – came to concern themselves with abolition. in 1783 the Quakers presented the first anti-slavery petition to the English Parliament.

That same year, large numbers of the public were shocked by the highly publicized court case brought by an insurance company against the owners of a slave ship, the Zong. Captain Luke Collingwood had sought to claim insurance on the 132 enslaved Africans he threw overboard when the vessel ran out of drinking water. During the hearing it was argued that “the case of slaves was the same as if horses had been thrown overboard”. Hearing humans being equated with horses must have sickened many, particularly the activist Granville Sharp who famously used the case to agitate in favour of abolition.

By the late-1780s then, anti-slavery had gown to be a popular cause, with more and more of the British public convinced of the immorality of the trade. In 1787, the movement was formally manifested in the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Also known as the London Committee, it was established by William Wilberforce, Sharp, and Thomas Clarkson, whose Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1786) was a key text in the battle against human bondage.

The committee was conceived to distribute Clarkson’s essay and other abolitionist publications. It was also used as a vehicle of innovate activism – which included petitions, boycotts, open meetings, parliamentary lobbying, and community organising across the country – to drum up public support for abolition.

Josiah Wedgwood and the Anti-Slavery Cause

There is no doubt that Josiah Wedgwood benefited from the slave trade. Making his fortune through pottery, his production profited enormously from the luxury market built off the back of slavery. He was able to capitalize with products such as tea sets, for example, as sugar brought from the New World helped to solidify the middle-class ritual of tea-drinking (with sugar used widely as a sweetener in tea). Plus sales of his luxury items were dependent on the network of aristocratic families, whose fortunes were made, or bolstered, by plantation profits. He was also able to find new markets in the West Indies for wares that have gone out of fashion in Europe.

His friendship with Thomas Clarkson, however, aroused his interest in slavery, and by the mid-1780s he had become utterly convinced of the immorality of the trade. When the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was inaugurated in 1787, he was one of thousands to join. Presumably because his name carried much weight, within months he was Invited to join the Society’s Committee. From the start he took his responsibility very seriously, attending seven meetings in 1788 and at least one in every succeeding year.

Ultimately for Wedgwood, the case for abolition was one of equality and a belief in the ‘rights of man’. Although he was personally disappointed by the reactionary apathy of other businessmen, he strongly believed that more and more people would commit themselves to the cause, not to be satisfied “whilst the national character is stigmatised by injustice and murder”.

Over many years, Wedgwood wrote impassioned letter, circulated petitions, attended meetings and joined boycotts. He also purchased shares in Clarkson’s Sierra Leone Company, established in 1791 as an evangelical colony in West Africa for freed slaves specifically designed to disrupt the Atlantic trade.

Wedgwood Medallion

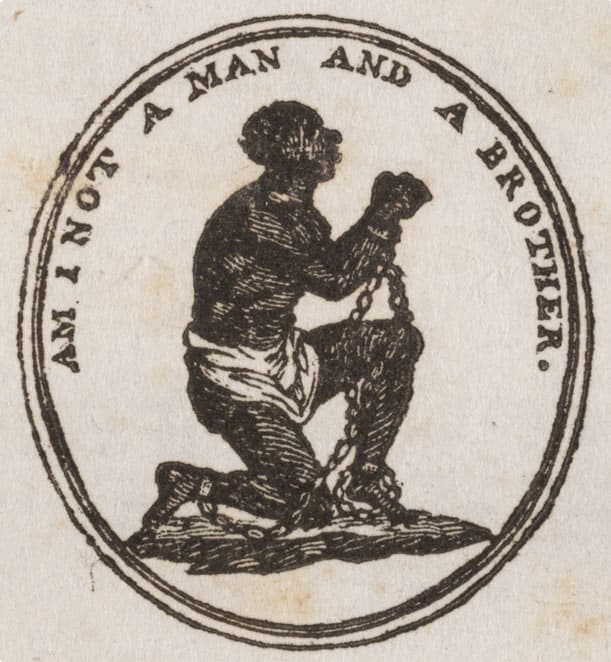

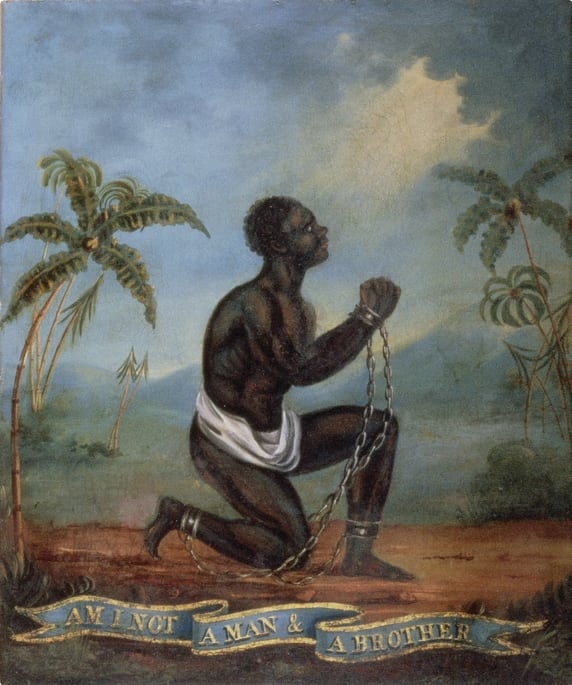

Wedgwood’s major contribution to promoting the anti-slavery cause though was undoubtedly his iconic slave medallion, first made in 1787. Composed of white jasper with a black relief and mounted in gilt-metal, the oval cameo depicts a chained African male slave in a half-kneeling posture facing right. On the edge are inscribed the motto: ‘Am I not a Man and Brother?’

The sculptor Henry Webber drafted the figure, with his design subsequently modelled at the Wedgwood factory at Etruria, Staffordshire by the Jasper specialist William Hackwood. It is fair to suggest that Wedgwood would have had some influence over the eventual design, and as he is popularly credited as the originator of its motto, the piece is considered a Wedgwood ‘original’.

The medallions were distributed for free through the abolitionist society network to promote the cause. By the 1790s, it is believed that thousands of medallions had been distributed. This included a quantity sent to future Founding Father Benjamin Franklin in America for distribution in Pennsylvania. As a result, it soon became the dominant motif of anti-slavery activism in the U.S., until illustrations from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin overtook it in the mid-19th century.

In Britain too, the medallion served as a popular icon for the abolition of the slave trade, an emblem carried forward by prominent abolitionists. As an exemplary piece of anti-slavery propaganda, it expressed the horror and barbarity of the slave trade, while appealing to the reason and sentiment of late-eighteenth century men and women to unify and put an end to the practice. As such, Hunt describes it as “one of the most radical symbols in modern history… part of British public memory as one of the pioneering symbols of political mobilization and globally engaged Victorian society”.

A Fashion Accessory

Wedgwood’s slavery medallions were so popular amongst supporters of the cause that they became something of a fashion accessory, worn as shoe buckles, pendants, brooches, and more. Thomas Clarkson described how both sexes took it upon themselves to customize the piece at their own expense. Men would set theirs in metal mounts or inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff box. Women, meanwhile, would wear theirs as bracelets or have them inlaid in hair pains. “A fashion… was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, freedom, humanity and freedom,” Clarkson wrote.

Although it may seem startling that such an image of human suffering was used in such a manner, there was a mutually reciprocal advantage in doing so. Frivolous jewellery was lent moral value by the use of an image associated with a popular and honourable cause. And the rather bleak medallion was made more accessible to women by transforming it into a noticeably feminine decorative luxury.

As the image itself is unashamedly masculine, feminizing the medallion in such a manner would have also helped to lessen any embarrassment women felt wearing images of a semi-naked black male. Male wearers, meanwhile, would not have encountered such problems. The simple mount into which the medallions were usually set was already a recognizably ‘male’ ornament, derived from the Renaissance medal.

Conflicting Meanings

Several confused and conflicting meanings can be drawn from the representation of the slave on Wedgwood’s medallion. On the one hand, the shackled and submissive figure is depicted as a means to evoke sympathy and a sense of magnality in its call for equality. But in doing so this representation ultimately perpetuates and reinforces harmful racial myths of the black man as weaker and inferior to the white.

Guyatt writes, “If at a certain level they [the abolitionists] aimed to present the slave as someone who shared everything in common with them except for the colour of his skin, on another level they clearly meant to keep their distance.”

At first glance, the figure on the medallion is a simple depiction of human suffering designed to communicate the abolitionists humanitarian concerns. Characteristically African features enable the viewer to grasp instantly that the figure portrayed is an African slave. This purposely depersonalizes him so that he can represent his entire race and thus remind the audience of the scale of the crime abolitionists felt slavery to be.

This is complimented by the motto, “Am I not a man and a brother,” which calls for the black African to be regarded a fellow human being rather than a separate species, as slave owners and traders saw them to be. Meanwhile, the slave’s position – kneeling with one knee upon the ground and with both hands pleading to Heaven – invokes figures from Christian iconography. As this was a time when many slaves took the Christian religion, such a representation can further suggest the commonalities they share with Europeans of the same faith.

On the other hand, the depersonalised nature of the slave can be seen to reinforce a categorization of black Africans as impersonal objects that white men could manipulate for certain economic purposes. Moreover, the bended knee, heavy chains, pleading hands and appeal to mercy all position the slave as helpless, unthreatening, and submissive. As well as to Heaven, it is implicit that his appeal is addressed to white society.

Guyatt writes, “Since supplication demands that a hierarchy of power is established, the slave is clearly the submissive party, a non-threatening object whose purpose is to arouse pity in the hearts of potential converts to the abolitionists’ cause.” The slave, depicted as surrendering to the white man’s will, suggests a condescending attitude towards him and his kind.

Despite the medallion’s stereotypical extremes, however, one must remember that it was intended as a piece of political propaganda – and propaganda is not known for its use of moderate images. The medallion’s purpose after all was to communicate its subject speedily and positively, whilst simultaneously gaining the viewer’s sympathy. Guyatt argues, to do so, the designers had to use the only conceptual framework they had before them – “a framework so informed by established racial stereotypes that it was perfectly permissible to present the slave as a man like themselves one moment, and as a hero or a victim the next.”

Despite their contradictions and hypocrisies, the British campaigners for the abolition of slavery would enjoy astonishing success in achieving their aims. By employing a wide range of strategies, from the production of artefacts like this medallion, to petitions, consumer boycotts, prayer days, and the distribution of leaflets, pamphlets, and printed images, they finally secured the abolition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807. By 1833, the emancipation of enslaved people in all the colonies of the British Empire had been achieved too.

Tour of Britain

Odyssey Traveller offers several small group tours to Britain for mature and senior travellers interested in learning more about Josiah Wedgwood and Industrial Britain.

Key tours include:

- Queen Victoria’s Great Britain Tour (21 days)

- Agrarian and Industrial Britain Tour (23 days)

- Canals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour (23 days)

We also have several other tours exploring the sights and history of the British Isles.

Odyssey Traveller has been serving global travellers since 1983 with educational tours of the history, culture, and architecture of our destinations designed for mature and senior travellers. We specialise in offering small group tours partnering with a local tour guide at each destination to provide a relaxed and comfortable pace and atmosphere that sets us apart from larger tour groups. Tours consist of small groups of between 6 and 12 people and are cost inclusive of all entrances, tipping and majority of meals. For more information, click here, and head to this page to make a booking.

Articles about Britain published by Odyssey Traveller.

- The London Underground

- Victorian Women’s Fashion

- Queen Victoria’s Britain, Part 1 and Part 2

- Understanding British Churches

- Studying Gargoyles and grotesques

- Georgian Architecture

- London’s Victorian Architecture

- The Industrious Revolution in Britain

- 18th Century London

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to Britain

- National Parks UK

- William the Conqueror (History.com)

- Queen Victoria

- The Royal Parks of London

- The Royal Mausoleum

Related Tours

23 days

AprAgrarian and Industrial Britain | Small Group Tour for Mature Travellers

Visiting England, Wales

A small group tour of England that will explore the history of Agrarian and Industrial period. An escorted tour with a tour director and knowledgeable local guides take you on a 22 day trip to key places such as London, Bristol, Oxford & York, where the history was made.

From A$17,275 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Sep, JunQueen Victoria's Great Britain: a small group tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of England that explores the history of Victorian Britain. This escorted tour spends time knowledgeable local guides with travellers in key destinations in England and Scotland that shaped the British isles in this period including a collection of UNESCO world heritage locations.

From A$15,880 AUD

View Tour

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$17,860 AUD

View Tour

From A$13,915 AUD

View Tour

21 days

May, SepExplore the History, Culture & Wildlife of West Africa: Ghana, Togo & Benin

Visiting Benin, Ghana

This small group tour for couples and solo travelers concentrates on the history, culture and wildlife of coastal Central Africa. Meet the friendly local people and come to a greater understanding of just what has made them what they are today.

From A$14,995 AUD

View TourRelated Articles

Britain: First Industrial Nation

Britain: The First Industrial Nation In the mid-18th century, the Industrial Revolution was largely confined to Britain. Historians and economists continue to debate what it was that sparked the urbanisation and industrialisation that would change…

Capability Brown: The English Garden Genius

Article for senior couples and mature solo travellers interested in gardens and design in England and Europe with small group tours of interest.. Brown is regarded as a genius.

England's Consumer Revolution

Article about the arrival of luxury brands and leisure time in England. Story supports small group tours to Britain and it's history from the Bronze age to the Romans, Vikings, Medieval period through to the industrial revolution and the wealth created. An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers.

Exploring Jane Austen’s England

Exploring Jane Austen’s England Jane Austen The reach and magnitude of Jane Austen’s influence on modern readers may make one forget that she only had six novels to her name (three of which were published…

Georgian Style of Architecture: Definitive Guide for Seniors

Article to provide the senior couple or mature solo traveler with an appreciation of the influence of Georgian Architecture in Britain when on a small group educational tour.

Industrial Revolution. Britain's contribution to the world

Britain and the industrial revolution. A progressive period that spanned Queen Victoria's period. Small group package tours for mature and senior travellers explore this fascinating period of history across England and Scotland and key cities such as Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle and Glasgow.

Wedgwood's Etruria, England

Article about Josiah Wedgwood, canal builder as well as potter, part of the the industrious revolution leading to the industrial revolution. An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers.