History of the Trans-Siberian Railway

History of the Trans-Siberian Railway The history of the Trans-Siberian Railway, a network of railways connecting Moscow to the Russian Far East, covers important events of the 20th century, tracing the rise and fall of…

6 Jan 20 · 13 mins read

History of the Trans-Siberian Railway

The history of the Trans-Siberian Railway, a network of railways connecting Moscow to the Russian Far East, covers important events of the 20th century, tracing the rise and fall of the Russian Empire. Spurred by Imperial Russia‘s industrial aspirations and expansionist dreams, the railway now runs the length of 9,289 kilometres (5,772 miles) across the Siberian wilderness. It became the precursor of a war with Japan and revolutions within Russia’s territory, serving as both a symbol of Soviet power and therefore an object of scorn for rebels, a deathtrap for the prisoners of Stalin’s Gulag, and a lifeline during World War II.

Odyssey published and article on Travel advice for the Trans Siberian railway.

Odyssey also published an article with travel advice for taking the Trans Siberian railway. You can read this article by clicking through on this link.

Russian Occupation of Siberia

If Siberia were a country in itself, it would be the largest country by area at 13.1 million square kilometres (5,100,000 sq mi). Today it accounts for 77% of Russia’s total land area.

Before Russians took over the region, Siberia, known for its long and severe winters, was inhabited by several small ethnic groups who were either hunter-gatherers or pastoral nomads raising domestic reindeer, cattle, and horses. In 1581, a Cossack expedition led by Yermak Timofeyevich captured Isker, capital of the khanate of Sibir (from which Siberia derives its name), beginning Russia’s expansion into the region.

Russian traders and Cossack explorers built the towns of Tyumen (1586), Tomsk (1604), Krasnoyarsk (1628), and Irkutsk (1652).

The Russians generally did not interfere with the Siberian indigenous peoples’ way of life, although there were tribes who succumbed to imported diseases brought by colonisation. Russian rulers demanded tribute, first in the form of furs, which, upon the decline of the fur trade, turned into a demand for silver and other metals mined in the vast wilderness.

China Halts Russia’s Eastward Expansion

Russia’s expansion to the east eventually encroached on Chinese territory, which was halted by the Treaty of Nerchinsk, signed in 1689 between Russia and the Manchu Chinese Empire. The peace treaty removed Russia’s outposts from the Amur River basin, losing what could have been Russia’s easy access to the Far East.

In exchange, the treaty allowed Russia to secure its claim to the area east of Lake Baikal, and a right of passage to Beijing for its trader caravans. The treaty was confirmed and expanded by the Treaty of Kyakhta in 1727 and remained the basis of Russo-Chinese relations until 1860.

Connecting Russia to the Far East

Though Siberia had been under Russian control since the 17th century, it remained a distant and exotic territory for European Russians, who had no practical way of travelling to and across the massive region that extends from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east.

Nikolai Muravyov, appointed governor-general of Eastern Siberia in 1847, was a strong advocate of developing the Far East and of creating a railway that would cut across Siberia. Siberia by then was still sparsely settled and undeveloped, seen mainly as a place of exile for prisoners and critics of the tsar. By the time of Muravyov’s appointment, Russia only has one passenger railway, the 24-kilometre railway connecting St Petersburg, the imperial capital, to the tsar’s summer residence, Tsarkoe Selo, to be followed in 1851 by a 650-kilometre railway connecting St Petersburg to Moscow.

Efforts to modernise Russia, such as Muravyov’s proposal, were rarely embraced by Russia’s landowning aristocracy. These nobles, to whom the Russian tsar was beholden, derived their wealth and privilege from the labours of serfs who toiled on their land, and saw no personal gain in transitioning from agriculture to new forms of industry.

Meanwhile, Russia’s chief imperial rivals–Britain, France, and Germany–were moving quickly towards mechanisation, shifting from water and wind to steam power, improving agricultural productivity and transportation. Imperial Russia was getting left behind.

In March 1891, tsar Alexander III officially announced the building of a Trans-Siberian Railway. His son and heir apparent Nicholas laid the first stone at Vladivostok (“lord of the East”), marking Russia’s entry into the industrial race.

Sergei Witte and the Manchurian Diversion

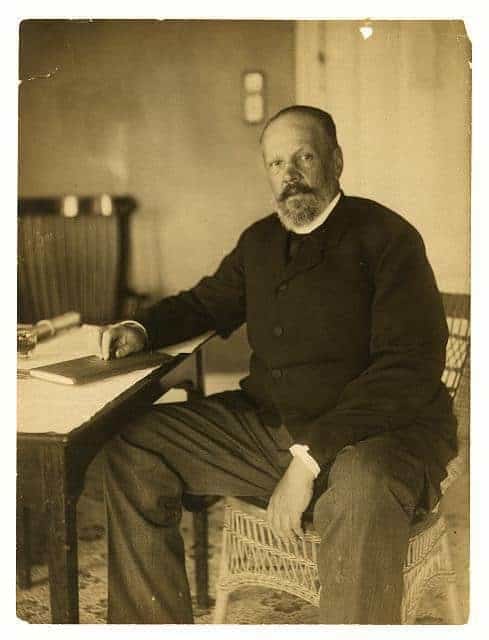

A key figure in the arduous task of building the Trans-Siberian Railway was Finance Minister Count Sergei Witte. (He would later be appointed Russia’s first Prime Minister in 1905.) Of Dutch-Russian origins and a graduate in mathematics, Witte originally planned to join academia and become a mathematics professor, but was persuaded to build a career in the railroad industry. He rose through the ranks in Odessa Railways, from ticket seller to its company director.

Witte understood railroads, but this new project required political manoeuvrings and an enormous amount of cash to ensure its completion. He persuaded Alexander III to name Nicholas chairman of the Siberian Railway Committee, guaranteeing constant royal support for the ambitious enterprise.

To pay for the railway, Witte issued bonds, raised taxes, took out foreign loans, and even printed extra roubles, which triggered a wave of inflation.

The construction of the railroad began in 1891 and proceeded simultaneously in several sections.

- Western Siberia (1892-96): The railway ran from Chelyabinsk (no longer part of the Trans-Siberian Railway) through Omsk and to the site of present-day Novosibirsk. This line was the easiest to build, as the main challenge was going across rivers, which was easily solved by building bridges.

- Eastern Siberia (1891-97): From Vladivostok to Khabarovsk through the Ussuri River valley. This proved more difficult as the railway would go through forest terrain. Labour shortages led to Russia employing Koreans and migrant Chinese labourers, who were paid less than the Russian workers. Later, convicts and exiles were introduced to the line and ordered to dig.

- Central Siberia (1893-98): From Ob to Irkutsk, through mountainous terrain.

- Trans-Baikal (1895-1900): From the eastern shore of Lake Baikal to Sretensk. The line had to scale the Yablonovy Mountains, 5,650 metres above sea level.

In 1896, or five years after construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway began, Witte approached the Qing emperor and proposed to build a shortcut across Manchuria (the historical region of northeastern China) instead of following the bend in the Amur River to Vladivostok–the same encroachment on Chinese territory that was halted by the Treaty of Nerchinsk.

The diversion would shorten the length of the railway by around 1300 kilometres (or 800 miles) and provide a means for Russia to trade in Manchuria. Initially rebuffed by China, Witte changed tactics and repackaged his proposal as a Chinese-Russian joint venture, and emerged victorious with an 80-year lease agreement forming the East Chinese Railway Company and Russo-Chinese Bank. The East Chinese line was finished in 1901.

In 1898, Witte negotiated further, and the Russians were allowed to build a Southern Manchurian line to snowless Port Arthur (now Lüshunkou District), on the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria.

Expectation and Reality: Exposition Universelle in Paris

By 1900, Russia was eager to show off this engineering feat. The ministry of communications commissioned promotional brochures printed in four languages and a massive “Palace of Russian Asia” pavilion displayed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, a world’s fair that celebrated achievements of the past century.

Inside the pavilion, visitors could sit inside mock first-class sleepers and view the landscape through a moving panorama painted in watercolour showing the Urals, Siberia, and Manchuria. The salon cars were decorated with French Empire furnishings (notably in the style of Louis XVI) with silk upholstery on the armchairs and sofa, and a piano. The pavilion also featured a library, a gymnasium, a hairdressing saloon, and a marble-and-brass bath. The brochures proudly proclaimed that it would only take 10 days to travel between Moscow and Vladivostok or Port Arthur.

Actual travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway, however, fell short of its promise of luxury. The trains routinely ran out of food, and after experiencing numerous accidents, were forced to travel at a snail’s pace of 25 km/hr (15.5 mph) to avoid derailment.

Though the railway disappointed luxury travellers, it greatly helped Russian peasants who wanted to move to Siberia. Half a million people resettled in Siberia from 1860 to 1890, but from 1891 to 1914, this number exploded to five million people, who travelled in cramped but cheap 3rd-class carriages on the Trans-Siberian Railway to become Siberia’s new immigrants.

The Railway Triggers a War with Japan

Unbeknownst to Witte, his agreement with the Qing Dynasty had triggered the suspicions of an emerging power in the East: Japan.

In 1876, Japan opened Korea to trade through gunboat diplomacy (or a grand display of naval power), similar to the way Commodore Perry forcibly opened Japan’s ports with his “black ships” in 1853. This was less than a decade after the Meiji Restoration and Japan’s adoption of Western military technology.

Korea at the time was a tributary state of China’s Qing dynasty and traded exclusively with China. Through a treaty, Japan forced Korea to declare itself independent from China and to open its ports to Japanese trade.

Japanese and Chinese forces clashed in 1894 during the Tonghak Uprising, a Korean peasant rebellion that aimed to exorcise Western influence and called for social reform. The Korean government asked for aid from China, who responded, but the Japanese sent in troops as well. The rebels were forced to step aside as what was to be later called the Sino-Japanese War raged, with Japan emerging as the unlikely victor in 1895, catching the Qing Dynasty unawares.

The end of the war saw China recognising the independence of Korea and ceding territories including Taiwan, Pescadores, and the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria to Japan. Intercessions by Russia, France, and Germany, however, forced Japan to modify the treaty and return the Liaodong Peninsula to China.

When Witte met with the Chinese emperor a year later and procured an agreement with the Qing Dynasty, Japan interpreted it as an invasion on a territory that Japan wanted for itself. What Russia did next certainly did not abate Japanese suspicion: in 1900, Russia sent 170,000 troops into Manchuria and occupied it in response to the Chinese peasant rebellion that foreigners dubbed the “Boxer Rebellion”. Russia would not have been able to send in so many soldiers to the Chinese territory if not for the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Russia and Japan clashed in 1904 in the Russo-Japanese War, with Japan launching a surprise attack on the Russian naval squadron at Port Arthur. Russian engineers at this point was building the Circumbaikal line, across Lake Baikal. The lake could sometimes prove impassable when it froze over during the winter. In urgent need of troops and supplies in Manchuria during the Russo-Japanese War, the Russians laid temporary tracks on the frozen lake to expedite transport. The train, unfortunately, sank through the ice.

Russia, in the end, proved to be no match to Japan’s military strength. In 1905, Japan emerged victorious, the first such victory of a non-Western country against a Western power. Japan gained control of the Liaodong Peninsula and the South Manchurian Railway, as well as half of Sakhalin Island. Russia agreed to evacuate southern Manchuria, which was returned to China.

Russia proceeded to build a longer and more difficult alternative route, the Amur Railway (1907-16), to Vladivostok, which became the Trans-Siberian Railway’s final section. After 25 years, the Trans-Siberian Railway was finally complete.

Wars and the Trans-Siberian Railway

Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War spurred protests against the tsar and led to the 1905 Russian Revolution. Railroad workers organised coordinated strikes and created the All-Russia Union of Railroad Workers, demanding better working conditions.

The revolution ended when the tsar Nicholas II, who was choosing between declaring a dictatorship or granting a constitution, chose the latter solution (though Witte as Prime Minister had reservations) and issued the October Manifesto, transitioning Russia from an autocratic empire to a constitutional monarchy with a legislative body called the Duma.

But a new constitution could not repair the tsar’s eroding reputation, further ruined by Russia’s losses in World War I. Nicholas and the tsarist regime fell in the February 1917 revolution, and was replaced by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks in October 1917. The fallen tsar and his family (Tsarina Alexandra and their five children, along with three servants and the family physician, Dr Yevgeny Botkin) were detained following Nicholas’s forced abdication and were killed by firing squad in Yekaterinburg by their Bolshevik captors in 1918.

The Bolsheviks’ claim to power was challenged by several factions from both right- and the left-wing armies, leading to the Russian Civil War. The anti-Communist White Army and Czech prisoners of war, the Japanese, and a separatist Siberian Republic led by Alexander Kolchak each seized control of sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The Bolsheviks’ fought in the Russian civil war for three years before finally wresting control of the railway away from the factions. Kolchak was later meted the death penalty in Irkutsk.

During World War II, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa (1941), and Russians moved east to Siberia for safety. Even Lenin’s body was removed from Moscow and freighted to Tyumen. The exodus from the Nazis led to the industrialisation of Yekaterinburg, Tyumen, Novosibirsk, Barnaul, and Krasnoyarsk, with the Trans-Siberian Railway serving as a lifeline.

Stalin’s Gulags and the Railway to Nowhere

In December 1922, the formation of the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” (USSR) was ratified. Lenin died two years later, and he was succeeded by Joseph Stalin, who served as secretary-general of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–53) and premier of the Soviet state (1941–53). Stalin was a ruthless leader who, as Ronald Francis Hingley (2018) describes, “destroyed the remnants of individual freedom and failed to promote individual prosperity, yet…created a mighty military–industrial complex and led the Soviet Union into the nuclear age.”

One of Stalin’s projects was a railway in the Russian Far North that would run from Igarka to Salekhard, measuring 1,297 kilometres (or 806 miles) in length. The planned railway, called the Trans-Polar Mainline, would facilitate export of nickel and connect the deep-water seaports of Igarka and Salekhard with the western Russian railway network.

It was also known as the “Dead Road” as the labour force for the railway was made up almost entirely of “enemies of the people“, or prisoners convicted of “anti-Soviet” offences from Stalin’s network of prison camps called the Gulag (an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or Main Camp Administration).

The prisoners were forced to work on the “Stalinbahn” in unforgiving weather. Salekhard, apart from Rovaniemi in Finland, is the only city in the world to cross the Arctic Circle. In winter, the temperature in Salekhard can go down to -50 Celsius (or -58 Fahrenheit), and in summer, the terrible heat brings mosquitoes and gnats.

There are no records about the real death toll of the railway project, but estimates say 300,000 prisoners were made to work on Stalin’s railway, with nearly a third dying in the process.

By the time of Stalin’s death in 1953, prisoners completed 600 kilometres (370 miles) of tracks. The railway would never be completed, and the tracks sank back into the Arctic snow. A memorial in the form of a steam locomotive was erected in Salekhard in memory of the doomed project’s victims.

Lines Into the Far East

The modern-day Trans-Siberian Railway proper runs from Moscow to the Pacific in Vladivostok and typically takes seven days. Branch lines were created to move deeper into the Far East.

Trans-Manchurian

The Trans-Manchurian line connects Beijing to the Trans-Siberian at Chita, through the East Chinese Railway and the South Manchurian Railway, which were returned to Stalin when the Soviet Union entered the Pacific War. Stalin returned the lines to China as a symbol of goodwill to its Communist regime in 1952. The border was closed in the 1960s with the breakdown of diplomatic relations between the two nations but was reopened in the 1980s.

Trans-Mongolian

This line connects Beijing through Mongolia to Ulan-Ude, made possible by diplomatic ties between the Soviet Union and the Mongolian People’s Republic, a sovereign socialist state that cut ties with the Chinese Manchu Empire and maintained close links with the USSR. The line between Ulan-Ude and Naushki was completed in 1940, and was extended to Ulaanbaatar in 1949. It was connected to Beijing in the early 1950s.

Baikal-Amur Mainline (Baikalo-Amurskaya Magistral, or BAM)

This line begins west of Irkutsk, passing north of Lake Baikal to the Pacific coast. Put on hold after Stalin’s death in 1953, work on the line resumed in 1974 but encountered challenges due to poor management and lack of workers. The line was opened in 1991, but the Severomusky tunnel, a 15-kilometre tunnel built for the BAM, was only completed in 2003.

Travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway with Odyssey

The enormous work done to build the railroad amidst Russia’s long and troubled history makes travelling on the Trans-Siberian Railway all the more magnetic and profound.

Sources for this article are linked throughout, but another excellent reference is Lonely Planet Russia by Simon Richmond et al.

Odyssey’s Helsinki to Irkutsk tour on the Trans-Siberian Railway runs for 21 days and spends multiple nights in Helsinki, St Petersburg, Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Krasnoyarsk, and Irkutsk, with stops at Russia’s oldest national nature reserve, Stolby Nature Sanctuary, and Lake Baikal.

The 30-day Trans-Mongolia and Russia tour takes you on the Trans-Siberian and the Trans-Mongolian Railway lines. The tour begins in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, and concludes with a cruise on the waterways between Moscow and St Petersburg.

If you want to learn more about travelling on the Trans-Siberian Railway, read this overview, which includes tips on booking your ticket and preparing for the long train ride.

For a different pace and cultural experience, you may want to explore:

- Japan History by Rail tour which journeys through Japan on the shinkansen (high-speed train)

- French History by Rail tour which goes through Paris and the other cities of France; we have a 21-day tour and a shorter 11-day tour

About Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. We specialise in educational small group tours for seniors, typically groups between six to 15 people. Odyssey has been offering this style of adventure and educational programs since 1983.

We are also pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, visit our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

Originally published November 7, 2018

Updated on January 7, 2020

Articles about Russia published by Odyssey Traveller

- Trans-Siberian Railway History

- Trans-Siberian Railway travel advice

- Eight Amazing Rail Journeys

- Trans-Siberian Landscapes and Wildlife

- Early Russian History and its Key Figures

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to Russia

Related Tours

days

JulJourney through Mongolia and Russia small group tour

Visiting Mongolia, Russia

This escorted small group tour traverses this expanse, from Ulaanbaatar to St Petersburg; from the Mongolian Steppes to Siberian taiga and tundra; over the Ural Mountains that divide Asia and Europe to the waterways of Golden Ring. Our program for couples and solo travellers uses two of the great rail journeys of the world; the Trans Mongolian Express and the Trans Siberian Express.

From A$17,850 AUD

View Tour

days

Oct, MayHelsinki to Irkutsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Finland, Russia

Escorted tour on the Trans-Siberian railway network from West to East starting in Helsinki and finishing in Irkutsk after 21 days. This is small group travel with like minded people and itineraries that maximise the travel experience of the 6 key destinations explored en-route. Our small group journeys are for mature couples and solo travellers.

days

Apr, AugIrkutsk to Helsinki on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Finland, Russia

Escorted tour on the Trans-Siberian railway network from East to West starting in Irkutsk and finishing in Helsinki after 21 days. This is small group travel with like minded people and itineraries that maximise the travel experience of the 6 key destinations explored en-route. Our small group journeys are for mature couples and solo travellers.

22 days

OctKrasnoyarsk to Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Russia

Mature and solo travelers group Travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway for 22 days covering the second half of the Trans-Siberian journey, from Vladivostok to Krasnoyarsk to Vladivostok on the edge of Siberian Russia Small group journeys with a tour leader, explores 5 key cities with local guides providing authentic experiences in each with stops of 2-3 nights.

From A$12,650 AUD

View Tour

days

Apr, AugVladivostok to Krasnoyarsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Russia

Mature and solo travelers group Travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway for 22 days covering the second half of the Trans-Siberian journey, from Vladivostok to Krasnoyarsk in the heart of Siberian Russia Small group journeys with a tour leader, explores 5 key cities with local guides providing authentic experiences in each with stops of 2-3 nights.