History of Berlin Germany for tourists

Discover the history of Berlin | Small group tours Germany Berlin is a city rich in history. At every turn are traces of a past plagued by conflict, and stories of powerful resistance. By the…

10 Oct 19 · 16 mins read

Discover the history of Berlin | Small group tours Germany

Berlin is a city rich in history. At every turn are traces of a past plagued by conflict, and stories of powerful resistance. By the 14th century, Berlin had established itself as a trade city. In the 15th century, the powerful Hohenzellorn came to power, first in the role of Elector before Friedrich III became King of Prussia in 1701. The Napoleonic occupation in 1806 set in motion a desire for self-governance, and the power of the Hohenzellorn dwindled until 1918, when it finally ended. But Berlin was then thrust into World War, and a series of political conflicts paved the way to Hitler’s taking power.

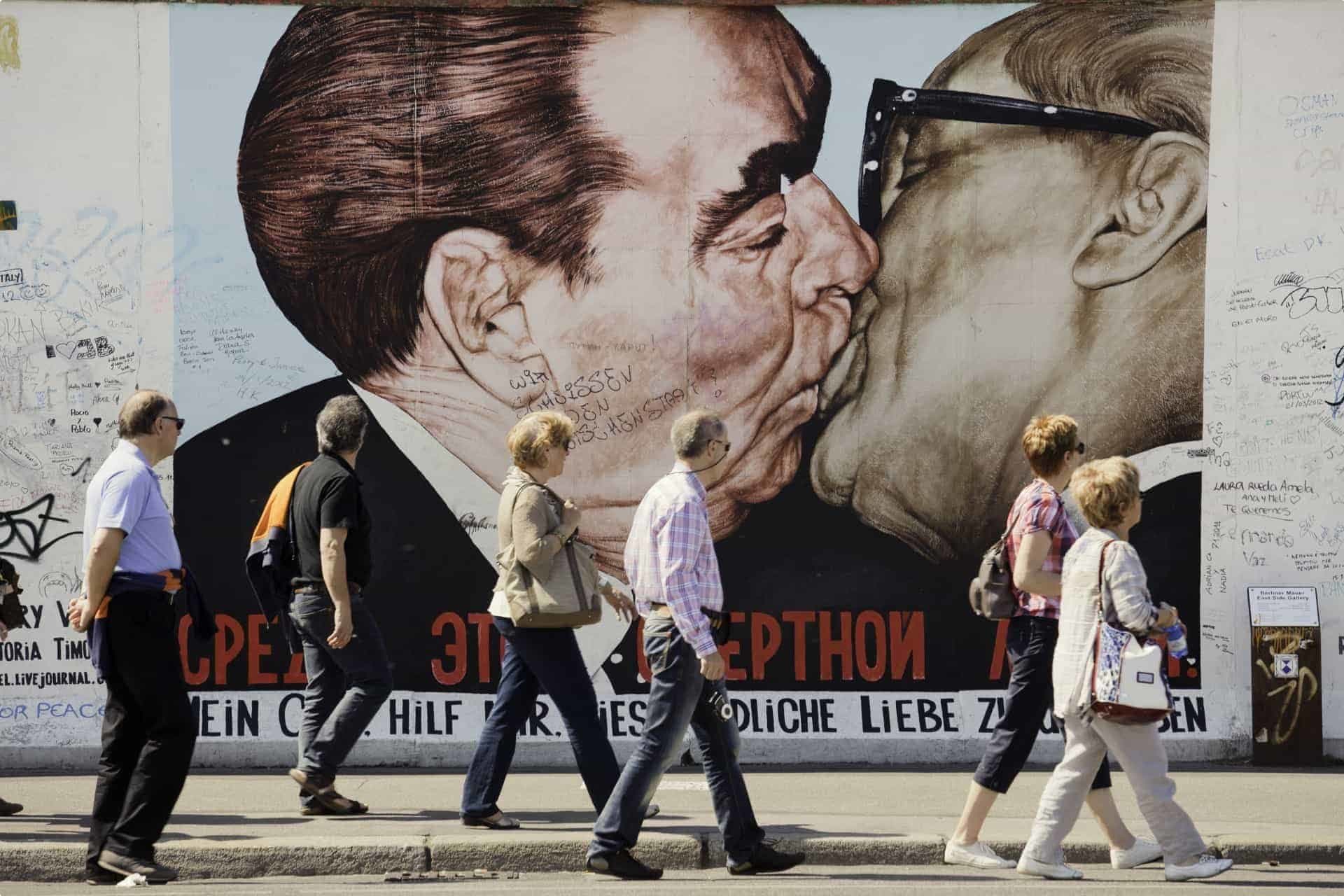

The outcome of World War II was a divided Berlin that culminated in its segregation, in the most obvious symbol of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall stood in place from 1961 to 1989, separating East from West. But after its collapse, the city transformed, and an influx of creativity and vibrancy is palpable wherever you go. While Berlin retains a sober awareness of its problematic past, it is also a city that continues to move forward and invites visitors to share in its progress.

This article aims to provide a usable guide to Berlin’s history for prospective tourists.

If you’re keen to visit Germany, we have several other articles and lists on our blog that may be of interest to you:

- The Bauhaus Movement

- The Oberammergau Passion Play

- A guide to Germany

- Fifteen must see sights in Berlin

- Ten books to read about Berlin

- Ten of the best art galleries in Europe

History of Berlin

Archaeological remains suggest Berlin was one of many villages in the area during Neolithic times. Arrowheads have been traced to the 9th millennium BC. The first indication of Germanic tribes is dated to 500 BC. But these tribes left the region in 500 AD, to be replaced by Slavic tribes. Traces of these settlements are nearby waters and plateaus – there’s no evidence to suggest they inhabited the area that is now Berlin City.

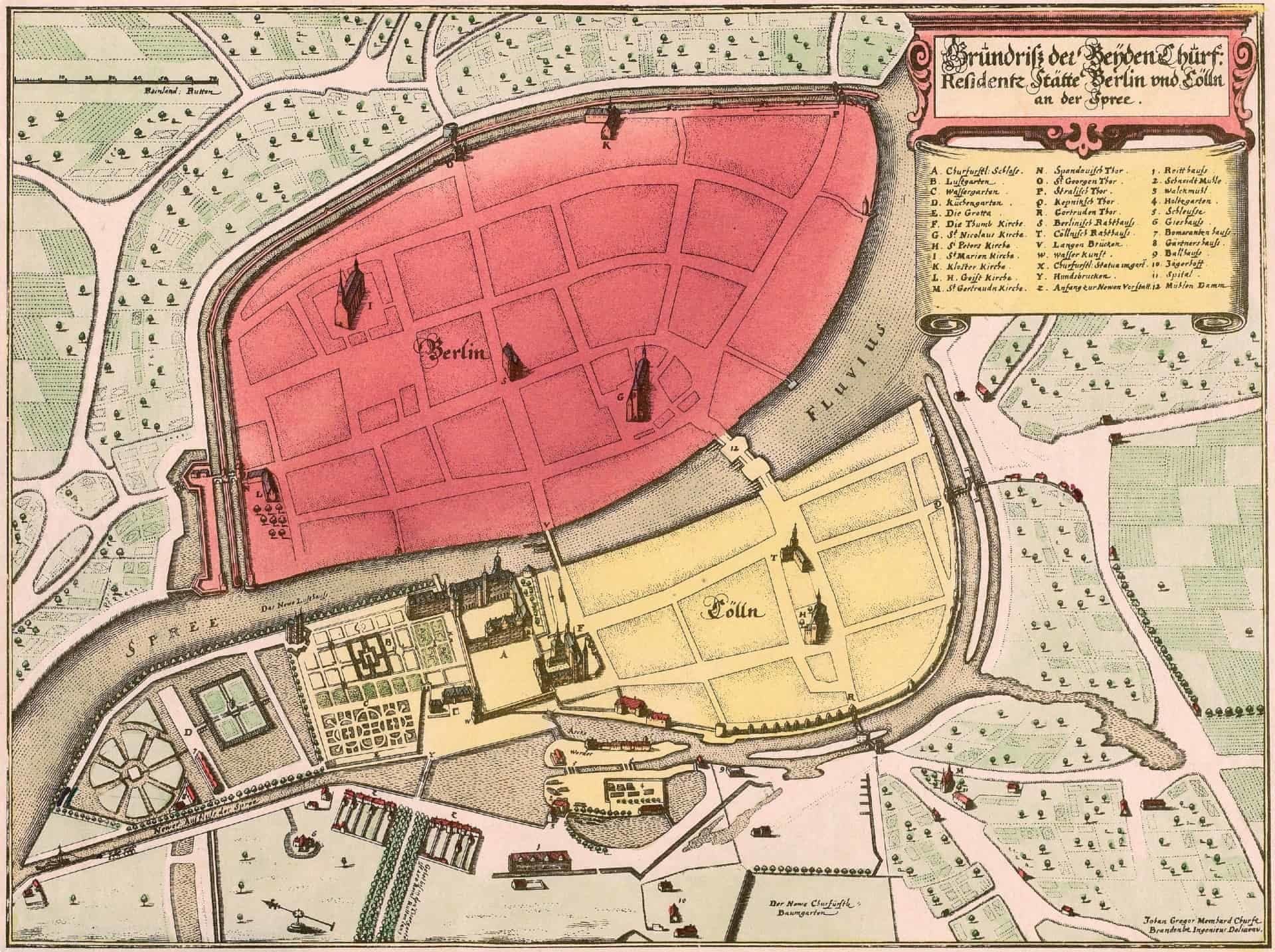

Berlin-Colln

The first recorded mention of Colln – the settlement that was to become Berlin – dates to 1237. This is considered the city’s official founding. Though there is some debate about which settlement was established first, it’s known that Berlin was situated close to Colln along the medieval trade route. The two towns flourished here and formed a union in 1307, while maintaining their own independence. The Ascanian margrave of Brandenburg lent his support to this move. But after his death in 1319, the merged town became very vulnerable to attacks. In spite of this, Berlin-Colln held strong. The town joined the Hanseatic League in 1360 in order to develop trade relations. By 1400, Berlin-Colln had a population of roughly 8500 people.

Elector Friedrich of Hohenzollern became Margrave of Brandenburg in 1415. As we will discover, this family was to remain in power until 1918.

A single municipality

In 1432, Berlin and Colln were officially merged to form a single municipality. Over the course of the next century, Berlin became the residence of Brandenburg Electors. This elevated the city’s political status, but cost it some of its freedoms.

The Reformation of Brandenburg

Come 1517, Martin Luther published his Ninety-five Theses, prompting academic discussion on the practices of indulgence that the Catholic Church condemned. His Protestant Reformation ideas eventually reached Berlin, and Elector Joachim II (ruled 1535-1571) took Lutheran communion in 1539. A new church ordinance followed in 1540, making the Reformation binding for all of Brandenburg. Church possessions were secularised, and money invested into constructing the palace of Berliner Stadtschloss, among other buildings. Berlin continued to prosper for the next decades until the Thirty Years War.

The Thirty Years War

This war, waged between Catholics and Protestants, had a devastating toll on Berlin. Elector Georg Wilhelm (ruled 1620 – 1640) attempted to maintain neutrality but Berlin was ravaged by both sides, leaving the city heavily damaged. Ensuing starvation and disease only compounded the impact on Berlin’s population.

The Great Elector

Georg Wilhelm’s son, Friedrich Wilhelm, came to power in 1640. During his long reign (till 1688), he managed to restore Berlin’s economic and political status. He built fortifications to protect the city from further attacks. He also installed a sales tax to fund the building of three new neighbourhoods, a canal, and gardens.

The “Great Elector’s” most important legacy was the Edict of Potsdam in 1685. As early as 1661, he had eased restrictions on immigration, encouraging refugees to settle in Berlin in order to restore its population. Fifty Jewish families from Vienna, and the expelled Huguenots from France, were among the city’s new residents. As a result of the Great Elector’s move, Berlin’s population tripled between 1660 and 1710.

King of Prussia

Friedrich Wilhelm’s son, Friedrich III, became elector from 1688 to 1701, and promoted himself to King of Prussia from 1701 till 1713. He made Berlin the royal residence and capital of Brandenburg-Prussia. During his reign, his love for the arts and sciences saw the establishment of the Academy of Arts in 1696, and the Academy of Sciences in 1700. In 1695, he built a castle for his wife, Sophie Charlotte. It was renamed Charlottenburg Palace following her death in 1705.

The great cultural and intellectual energies of the reign of King Friedrich I were undermined by his son, Friedrich Wilhelm I. During his 27-year reign (1713-1740), Friedrich Wilhelm I’s most notable act was establishing an 80,000 strong army. ‘The Soldier King’’s brutal conscription methods had men fleeing Berlin, till he rescinded the draft in 1730.

Friedrich the Great

While Friedrich Wilhelm I’s army never went into battle for him, they did for his successor: son Friedrich II (ruled 1740-86). ‘Friedrich the Great’ (or ‘Old Fritz’ as he is affectionately known in Germany), patronized Enlightenment thinkers and the Arts. But he was also a powerful military theorist. He fought Austria and Russia to successfully claim Silesia – now Poland. He also reformed the judicial system, abolished slavery, and allowed for freedom of press and literature. As a result, the city’s intellectual scene flourished: philosophers, artists, poets, musicians, naturalists and explorers flocked to the city to participate in its intellectual salons.

Because Friedrich II never fathered children, he was succeeded by his nephew, Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Sanssouci, Summer Palace of Friedrich the Great, Berlin

Interesting fact

Friedrich the Great is generally considered with affection, with the exception of some critics who question his treatment of Polish subjects. He is romanticised as a glorified warrior who helped attain Prussia’s powerful place in Europe. But his idolisation by the Nazi party saw him fall out of favour in Germany during the aftermath of World War II. Come the 21st century, however, his legacy has been rethought and Old Fritz is a revered historic figure once more.

The French Revolution

Unfortunately, nephew Friedrich Wilhelm II attracts less affection. It’s said that he was the antithesis to his uncle: pleasure-loving and indolent. The French Revolution exerted pressures that he did not adequately manage, and Prussia weakened. Meanwhile, he was opposed to Enlightenment ideals and pushed for traditional Protestantism. Remarkably, the arts still flourished under his patronage. There were magnanimous developments: Brandenburg Tor (Gate) was officially opened, and Prussia’s first highway was paved between Berlin and Potsdam. The first steam engine arrived from England, used by Johann Georg Sieburg to power cotton spinning machines.

Defeat by Napoleon, and a taste of self-governance

Friedrich Wilhelm II was succeeded in 1797 by son Friedrich Wilhelm III. This was a period of significant political unrest. Prussia was defeated by Napoleon in 1806 at Jena, a city 400km from Berlin. When Napoleon marched through the Brandenberg Tor, it signalled the beginning of a three-year occupation. Berliners were forced to billet French soldiers in their homes, and the city was subject to expensive war reparations. Interestingly, this period did give Berliners a taste of self-governance.

Once the French left, this spirit remained in Berlin. Friedrich Wilhelm III’s tokenistic reforms did not impress, because they failed to instigate meaningful changes. People questioned the right of nobility to hold the power. Meanwhile, cafes and salons continued to thrum with intellectuals and artists. Humboldt University opened in 1810, and drew the likes of Ranke and Hegel to Berlin.

Hopes of Reform

The first tenements were built on Gartenstrasse to house the influx of workers to the city, who were lured by the promise of steep economic growth.

Hopes of reform were rekindled when Friedrich Wilhelm III was succeeded by his son, Friedrich Wilhelm IV in 1840. He is often referred to as the ‘Romanticist on the Throne’. Many buildings were constructed during his reign, and the Cologne Cathedral was completed.

But he proved to be as conservative as his father. He staunchly opposed a liberalised Germany. By now, the growing city was poverty-stricken. Up to 40% of the city’s budget was allocated to caring for the poor. In the face of bourgeois revolutions and demands for democratic rights, Friedrich Wilhelm IV raised the income condition for election participation, meaning that just 5% of citizens were eligible to vote. This system continued till 1918. Unlike his father, however, he did make some concessions. He supported freedom of the press and permitted Berliners to assemble. But on the very next day, soldiers opened fire at a gathering of 10,000 people, killing 200. In the aftermath, warring factions were unable to negotiate a way forward, and the revolutionary spirit was quashed. The industrial revolution, meanwhile, bore ahead.

Military strategy

In 1857 Friedrich Wilhelm IV was left incapacitated by a stroke, and his brother, William I, became King. William I (ruled 1861-1888) was less averse to progress. Berliners were hopeful as he elected Otto von Bismarck as Prussian prime minister. Bismarck orchestrated a complex military strategy. Austria allied with Germany to defeat Denmark in 1864, but two years later, Prussia defeated Austria to form the North German confederation. Bismarck dreamed of a unified Germany. When France declared war on Prussia in 1870, he caught Napoleon III off guard by rallying the support of southern German states too. Soon, a unified Germany (called ‘Deutsches Reich’or the German Empire) was born. Berlin became the capital of the German Reich.

The Iron Chancellor

As people flooded to Berlin and the economy boomed, new political parties were in development. The General German Workers’ Association (founded 1863) and the Social Democratic Workers Party (founded 1869) united in 1875. The combined Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany was formed to give voice to the working classes. But Bismarck – by now the King’s ‘Iron Chancellor’ – did not approve of such democratic ideals. In 1878 he outlawed all meetings and publications of the so called ‘enemies of the German Reich’. His attempts to suppress the party only heightened its popularity, and this was Bismarck’s ultimate downfall. In 1890, he was stripped of his role as chancellor. In the same year, the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany was renamed the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Furthermore, the first May Day celebrations took place. The Reichstag elections saw the SDP claim a resounding majority.

The rise of the Social Democratic Party

Come 1918, Wilhelm II would transfer his power to the Social Democratic Party. When Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Austria, and World War I broke out, Berlin was in turmoil. Peace came at the cost of defeat, and Wilhelm II subsequently abdicated, fleeing for the Netherlands. The reign of the Hohenzellorn had come to an end. Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert became chancellor in 1918.

Symbolically, as Wilhelm II’s abdication was announced, Phillip Scheidemann stood on a balcony of the Riechstag and proclaimed the ‘Free German Republic’. And on a balcony of the Berlin Palace, Karl Liebknecht declared it the “Free Socialist Republic of Germany”.

The Spartacist League

Liebknecht was the son of the SPD founder. He, along with Rosa Luxemburg of the party’s left-faction, was unimpressed with the SPD’s participation in WWI. The pair were imprisoned from 1916-1918 for their role in rallying public protests against German’s involvement. They came to form the Spartacist (alternately, Spartacus) League, named for the leader of the largest Roman slave rebellion. The group published the Spartacist Manifesto in 1918. In it, they called for the employment of political power toward achieving socialism, and expropriating the capitalist class. The Spartacist League merged with other radical groups and renamed itself the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1919.

In this same year, the Spartacist Uprising took place, with protests against the centrist SPD. The government promptly quashed the uprising. Liebknecht and Luxemburg were arrested, and killed in custody by Freikorps (Free corps) troops.

The consolidation of democracy

Also in 1919, a new Berlin city assembly is elected, as democracy begins to take shape. This is unofficially called the Weimar Republic, and is headed by Ebert, and then Paul von Hindenburg: both of the SPD. Notably, 25 women are represented in the city parliament. However this government pleased neither the left nor right wings.

The Kapp Putsch

Within a year, an attempted coup rocked the Weimar Republic. Resentment among the right-wing nationalist and militarist circles was spurred by the so-called ‘stab in the back myth’, wherein Germany’s ‘alleged’ defeat was attributed to the attitude of civilians at home. The brave efforts of soldiers were thought to be underappreciated. This coup – the Kapp putsch – is named for Wolfgang Kapp, who is understood to have been planning to challenge the republic for some time. Though Kapp bears its name, the real force behind the attempted coup was the military.

A general strike in Berlin

When two of the most powerful Freikorps groups were ordered to disband according to the Treaty of Versailles, thousands of elite soldiers refused. General Walther von Luttwitz entered Ebert’s office with demands for the immediate dissolution of the National Assembly, and for his own appointment as supreme commander of the army. Commander of this right-wing group, Hermann Ehrhardt, ordered his brigade to overcome resistance with violence, as they marched through Berlin wearing swastikas. The government fled to Dresden. But as Kapp and Luttwitz took power, Berlin instituted a general strike. With the country paralysed, they were unable to govern.

Representatives of the democratic right were invited into negotiations, and the four main centre-right parties determined that rather than overthrow Kapp and Lutwitz, the two would need to be seen to resign voluntarily. The democratic right sought to reengage the officer corps, rather than further alienate them. They offered false passports which, as the coup began to unravel, Lapp, Luttwitz, and Ehrhardt each accepted. Though the Weimar Republic successfully overthrew the Kapp Putsch, some historians argue that this incident paved the way for the Republic’s dissolution in 1932.

Berlin’s growth

Meanwhile, beginning in 1920, Berlin began to grow rapidly. The government amalgamated the region’s different villages, so that Berlin suddenly became one of the world’s largest cities. While its 3.8 million inhabitants were plagued by poverty and disease, there were some causes for optimism: the introduction of the Rentenmark in 1923 had helped to stabilise Berlin’s inflated economy, and the 1924 Dawes Plan went some way toward alleviating the drastic reparations that were imposed on Germany after WWI.

A cultural revolution

Moreover, Berlin drew artists, architects, intellectuals and writers as the city experienced a cultural revolution to rival Paris. During this decade, the world’s first official highway was opened in Gruneweld – a suburb of Berlin. Foreign minister Walter Rathenau was killed by right-wing soldiers. He had helped to engineer the Treaty of Rapallo, which initiated cooperation between Germany and the soon-to-be Soviet Union. Tempelhof Airport opened in 1923, and the radio and television arrived in Berlin for the first time.

The Great Depression

But the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929. Berlin was plunged into the Great Depression. Mass bankruptcy and unemployment contributed toward a sense of volatility within the streets. Riots broke out between left and right factions: “Bloody May” saw 30 people killed and hundreds injured. The National Socialist Party (NSDAP) – better known as the Nazi party – received 5.8% of the vote in a November election. Three years later, it was the strongest party in parliament, at 25.9%.

The Nazi Party

President Paul von Hindenburg of the SDP appointed Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933. Hindenburg was responding to failed economic reforms, and increasing pressures from the far-right. The conservative forces believed they would be able to ‘contain’ the NDSAP. Of course, this mistake proved to be catastrophic. The Nazis celebrated the appointment with a torch-lit march through the Brandenburg Gate.

The mysterious Reichstag fire

A mysterious fire broke out at the Reichstag (parliament) on the 27th of February. Dutchman Marinus van de Lubbe was charged with arson. The Nazis characterised it as a Communist effort to overthrow the state.

The fire is thought to be one of the most significant moments in the rise of Hitler. Historians – and conspiracy theorists – continue to disagree about the causes of the fire. While some believe that the Nazis were behind the fire, others simply argue that they did an effective job of capitalising on it through powerful anti-Communist propaganda.

The Reichstag Fire Decree

A Decree for the Protection of German People was introduced by Hitler’s cabinet on February 4. This placed a temporary ban on political meetings and marches, and restricted press. But following the fire, a more permanent suspension of civil rights was instituted, known as the Reichstag Fire Decree. The regime was permitted to arrest and imprison political opponents without charge, and central government was given authority to overthrow state and local governments. As propaganda circulated, spreading fear of “bolshevism” or Communist takeover, the Nazi regime managed to attain far too much power. Come March 24, parliament passed the ‘Enabling Law’, effectively making itself redundant, and giving Hitler authoritarian control.

A regime of brutal force

What came next was a brutal regime that eliminated all perceived opponents, including the SPD, trade unions and communist groups. The brown-shirted Sturmabteilung upheld this regime with extreme force. Almost 100 people were murdered during a single week in June 1933. This is known as Kopenick Blood Week. ‘Un-German’ books were burnt, as intellectuals and artists fled in terror. Come 1935, Heinrich Sahm resigned – by now he was lord mayor by name only. Hitler’s army had control of Berlin.

The plight of Jewish residents

But of course, the main target was Jewish people. Approximately 160,000 Jews resided in Berlin in 1933. 90,000 emigrated before 1941, while over 60,000 died by the end of the war. Around 1400 survived by living in hiding, assisted by fellow Berliners.

The 1936 Olympics

At the 1936 Olympics, all indications of this regime of terror were concealed. Signs and slogans were removed from sight. As Germany excelled at the games, Hitler managed to distract the rest of the world from the atrocities being committed at his command.

The outbreak of World War II

But on September 1, 1939, Germany attacked Poland. The Second World War had begun. Bombs were landing upon Berlin within a year. At the 1942 “Wansee Conference”, the so called “final solution of the Jewish problem” was ascertained. High ranking Nazis and officials had met to discuss the mass killing of Jews – a distorted vision that they wanted to see implemented across Europe.

The Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad in 1942-43 led to a costly defeat for Germany. Nazis and allies fought the Soviet Union for the city of Stalingrad in Southern Russia. After initial success at pushing back Soviet defenders to the west bank of the Volga River, the Red Army retaliated with force. But Hitler ordered the army to stay put. After 5 months, and with their resources and ammunition supplies exhausted, they surrendered. Of the 91,000 German prisoners captured at Stalingrad, just 5,000 returned.

This was first time the Nazi party admitted their defeat. Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, famously declared Total War at a speech at Sportpalast. Germans were encouraged to sacrifice themselves for the Fuhrer.

The Battle for Berlin

Meanwhile, the Red Army and allied forces descended onto Berlin. Air raids were unrelenting, and Hitler was worried. In April 1945, the final Battle for Berlin took place. Hitler, with Eva Braun, his wife of just days, retreated into his bunker. He and Braun killed themselves. Berlin surrendered to the Soviets two days later.

Germany was left in tatters. Infrastructure was destroyed, and many Berliners died.

A divided Berlin

Politically, Germany had been divided into 20 administrative areas. They were distributed among the British, Americans, French, and Soviets. But tensions between these four powers developed almost immediately. When the Allies introduced the Deutschmark into their zones without consulting the Soviets, the situation escalated. The Soviet zone geographically surrounded West Berlin, and they declared an economic blockade as they tried to wrest control from the Allies. The Allies saved Berlin from this by supplying the city via air.

Friction among the divisions

As the division between these regions was formalised in 1949, friction persisted. The Western zone became the Federal Republic of Germany, and channelled money into its reconstruction. Meanwhile, the Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic. Movement between the states was open, though the GDR was alert to dissent, incarcerating ‘dissidents’ at the secret Stasi Prison.

Checkpoint Charlie: The erection of the Berlin Wall

In 1951, restrictions were implemented. Suddenly, West Berliners required a permit to travel outside the city. As East Berliners suffered from poor economic and living conditions, they tried to escape to the West. The loss of these mostly young and educated people was further harming the economy, and led East Berlin to erect the wall to restrain them. The Berlin Wall stunned residents on both sides. 200 people lost their lives trying to cross it until its collapse in 1989.

About our Berlin walking tour:

Exploring the city of Berlin on foot gives us a local’s perspective, meaning we see what tourists miss. On our walking tour, we use the Berlin Wall as an anchor. Each day we venture to a different section of the Wall, before exploring the historic and architectural diversity of this incredible city, from Rococo palaces to modern architecture, and contemporary design. Berlin is a surprisingly green city, and we take in its great rivers and majestic forests. The tour also includes a day trip to Potsdam, where we wander among the summer palaces of Prussian Kings. Our tour also includes several ballet and opera performances.

The tour is for clients who want to learn about their destination on tour. Each day we meet up with our guide, a local historian. Throughout the tour, we live like Berliners: we use public transport to get around, and return to serviced apartments in Central Berlin at the end of each day.

Visit Germany with Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller offers a variety of tours dedicated to Germany, while a number of our Europe tours include Germany as a key destination.

Our Germany tours include:

- Contemporary Germany: This tour captures the diversity of contemporary Germany, ranging from north to south, and taking in Germany’s most important cities: Munich, Dresden, Berlin and Cologne. If you’re interested in getting out of the cities and into Germany’s beautiful scenery (including a Rhine River cruise) this is the tour for you!

- Discovering Berlin: Over twenty days living in the city, this tour of Berlin gets off the beaten path. We delve into Berlin’s fascinating and often troubling history, uncover hidden gems, and experience the cutting-edge local culture. We also offer a 12-day walking tour of Berlin.

- Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle: For lovers of Wagner’s music, this tour gives you the opportunity to see four performances of his music in his home city, Leipzig.

- Bach, the man and his music: Another tour for classical music fans. This cultural tour is based around the Bach Music Festival in Leipzig, but includes visits to other cities lived in by Bach.

Germany is also visited on these Europe tours:

- Theatre, Opera, Ballet and Classical Music: This tour gives travellers the opportunity to attend performing arts concerts across four leading European cities: Hamburg, Amsterdam, Paris and London.

- The European Ballet: This tour takes in ballet concerts in cities across Germany and France.

- Discover Beethoven’s life and music: This tour traces Beethoven’s life and historical context across the cities of Bonn and Vienna. We also attend several performances of Beethoven’s work, including opening night at the Beethovenhalle in Bonn.

- Baltics Small Group Tour: This tour uncovers the history of the Baltic states: Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. In order to understand these countries caught between German, Scandinavian and Russian spheres of influence, the tour also includes Berlin, Poland, Helsinki and St. Petersburg.

In 2020, three of our tours – Contemporary Germany; The Habsburgs; and our Berlin tour – include a performance of the Oberammergau Passion Play.

In 1634, in the midst of a plague that swept across Europe, the residents of Oberammergau, a small town in the Bavarian Alps, promised God that if they were spared from plague they would perform a passion play every ten years. The residents have kept their pledge, performing the play every ten years. Today, the Oberammergau Passion Play attracts visitors from all around the world, and can sell out – so make sure to get into a tour quickly if you want to join us for the performance!

Related Tours

12 days

Oct, MayBerlin walking tour

Visiting Germany

Enjoy an escorted walking tour of Berlin. This small group holiday is for like minded people, mature couples or solo travelers who enjoy getting off the beaten track and exploring with some adventure. The itineraries set for each day follow sections of the Berlin Wall, whilst local guides realise authentic experiences found in this amazing city.

From A$8,745 AUD

View Tour

16 days

Jun, MayBach Classical European Music Festival small group tours

Visiting Germany

Enjoy the best of Bach travelling with mature couples or solo travellers in a small group tour. We take time to appreciate not just the music but also to explore Bach's history and influences in Germany. The program spends 16 days visiting the locations that where influences on his life as well as attending the Bach Music festival in Leipzig.

From A$13,340 AUD

View Tour

days

JulRichard Wagner Ring Cycle, Leipzig | Small Group Tours Germany

Visiting Germany

The small group tour will see the opera performed in the city of Richard Wagner’s birth, Leipzig. Our tour starts in Dresden and we also visit Bayrouth and Munich. We will not only experience his music in these 4 operas, but also be shown the influences of culture and family on the extraordinary composer’s life.