Five Women of the Renaissance

Five Incredible Women of the Renaissance | Small Group Tours The Renaissance stands as one of humanity’s most profound intellectual and artistic revolutions, often overshadowed by narratives of renowned men and their contributions. While historical…

8 Oct 19 · 13 mins read

Five Incredible Women of the Renaissance | Small Group Tours

The Renaissance stands as one of humanity’s most profound intellectual and artistic revolutions, often overshadowed by narratives of renowned men and their contributions. While historical focus tends to marginalize women in the Renaissance, there is a growing awareness of their presence and impact during this era. Despite societal constraints relegating women to limited roles like marriage or religious life, there are significant but often overlooked stories of women who defied norms and left their mark on history.

This article delves into the lives of five notable women who played pivotal roles in Europe’s cultural and artistic resurgence during the Renaissance. Exploring their lives offers a deeper understanding of how these trailblazers shaped the world around them and influenced future generations. Get ready to learn more about:

- Christine de Pizan (1364-1430)

- Isotta Nogarola (1418-1466)

- Marguerite of Navarre (1492-1549)

- Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589)

- Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625)

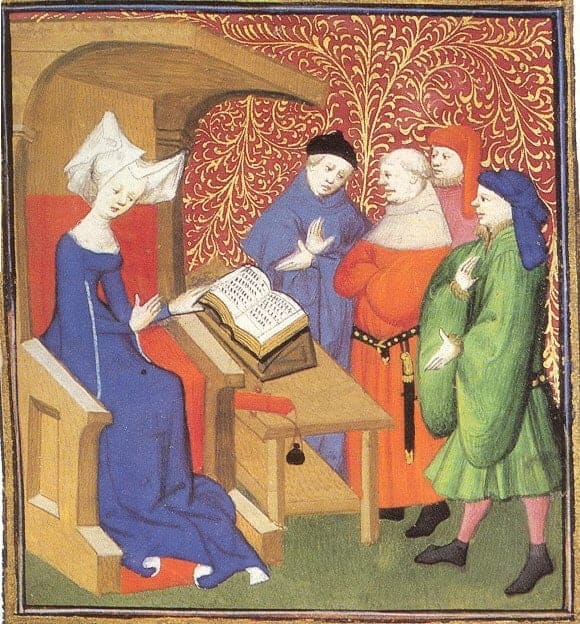

Christine de Pizan (1364-1430)

Christine de Pizan, a trailblazing medieval French poet, holds the distinction of being Europe’s first recognized professional female writer (Davis & Lindsmith, 2019, p. 19). Considered a proto-feminist avant la lettre, she fearlessly confronted misogyny and championed women’s rights during an era devoid of feminist ideologies.

Initially hailing from Venice, Italy, Christine’s life predominantly unfolded in France following her father’s employment at the court of Charles V as an astrologer. Despite her affluent upbringing within the French royal palace, her education was typically neglected, mirroring the limited academic opportunities for girls at the time. While her father nurtured her intellectual curiosity and literary ambitions, her mother adhered to traditional gender roles, emphasizing domestic duties over scholarly pursuits.

Marriage at the tender age of 15 to Estienne de Castel, eventual court secretary, marked a significant juncture in Christine’s life. Tragically, Estienne’s demise in 1389 left Christine, then 25 years old, widowed, and the sole provider for her three young children, prompting her to seek means of sustaining her family independently.

A Literary Career

Christine de Pizan defied the societal norms of her time by choosing a less conventional path for women in the 14th century. Instead of remarrying or joining a convent after the death of her husband, she ventured into writing to provide for her family. Initially crafting poems in honor of her late husband, her literary pursuits gained recognition among the aristocracy, including notable patrons such as Louis I, Duke of Orléans, Philip the Bold of Burgundy, Queen Isabella of Bavaria, and the 4th Earl of Salisbury. Their support ensured a stable income for Christine and her children.

A remarkably prolific writer, Christine authored a total of 30 volumes, with 10 dedicated to verse. Notably, her work “Letter to the God of Loves” (L’Épistre au Dieu d’amours) challenged the popular “Romance of the Rose” by Jean de Meun, criticizing its portrayal of men’s pursuit of women. She further championed women’s roles in society through her prose works, such as “The Book of the City of Ladies” (Le Livre de la cité des dames) and “Book of Three Virtues” (Le Livre des trois vertus), both released in 1405. The former, inspired by St Augustine’s “City of God,” allegorically illustrated the virtues of women, while the latter provided practical financial guidance for women based on her own experiences.

A defining moment in Christine’s literary legacy was her 1429 piece, “The Tale of Joan of Arc” (Le Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc), composed during Joan of Arc’s lifetime. In this work, Christine hailed Joan of Arc’s triumphs as a testament to the capabilities of women. Despite her passing in 1430, Christine’s impact endured through the wide circulation and translation of her works across Europe. Her writings challenged prevalent notions of femininity and women’s capabilities, offering progressive perspectives in an era rife with gender biases. Christine’s advocacy for gender equality and her eloquent critique of patriarchal systems continue to resonate, providing valuable historical insights into medieval gender dynamics that remain relevant today.

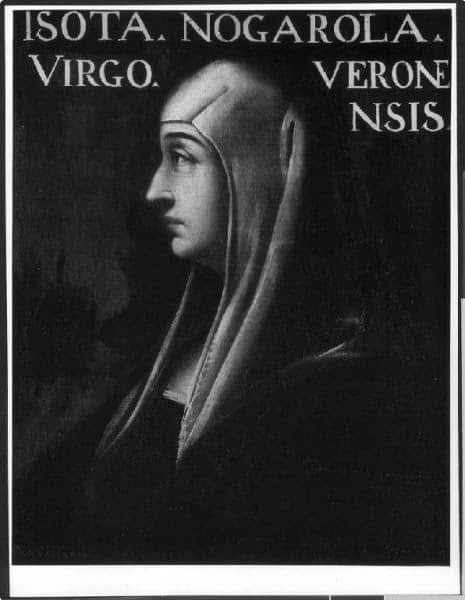

Isotta Nogarola (1418-1466)

Isotta Nogarola, born into a prominent Veronese family, quickly rose to scholarly prominence in her early twenties, recognized as a leading female humanist (Davis & Lindsmith, 2019, p. 78). Renowned as a pioneering female humanist, she played a pivotal role in the intellectual landscape of the Renaissance period.

During the Renaissance, Humanism emerged as a significant intellectual movement, originating in the 13th century and gaining dominance across Europe. This movement focused on the study of classical texts to transcend medieval ideologies and shape modern life. By the 15th century, Humanism had become the primary educational approach in Italy. Despite the prevailing norms that limited women, particularly from the upper echelons, from delving deep into classical studies, Isotta’s mother, the widowed Bianca Borromeo Nogarola, not literate herself, ensured that Isotta and her sisters received a comprehensive classical education under the guidance of Martino Rizzoni.

Isotta’s sister Ginevra, on the other hand, discontinued her humanist pursuits upon her marriage in 1438. In stark contrast, Isotta persisted in her scholarly endeavors. Engaging in intellectual discourse through letter-writing, a common scholarly practice of the time, Isotta stood out as one of the rare women in Europe who actively shared her written works (p. 79).

From Humanist to Religious Scholar

Renowned beyond Verona, Isotta’s scholarly reputation was tarnished by gender bias. An anonymous critic, threatened by her intellect, unjustly labeled her as promiscuous, claiming that a learned woman couldn’t be chaste. In a poignant letter to Guarino da Verona, her mentor’s mentor, Isotta questioned her fate as a woman and expressed her dismay at being scorned by men, ultimately retreating from humanist studies.

Despite the backlash she faced, Isotta resurfaced as a religious scholar, navigating a more socially acceptable path for women during that era. Opting not to marry or enter a convent, her family’s affluence enabled her to lead an independent life on her own estate, delving into religious texts in seclusion. Her seminal work, “Of the Equal or Unequal Sin of Adam and Eve” (De pari aut impari Evae atque Adae peccato) written in 1451, stemmed from her deliberations with scholar Ludovico Foscarini on the biblical conundrum surrounding Adam and Eve’s transgressions.

Tragically, Isotta passed away at the age of 48 in 1466, reportedly neglecting her health in her scholarly pursuits. Despite her struggles, her legacy endured with the posthumous publication of her letters, showcasing her intellectual prowess. Nearly 600 of her letters were discovered in a Parisian library in the late 17th century, underscoring the lasting impact of her writing. Isotta’s life exemplifies the challenges faced by women in academia, highlighting the societal contempt they endured for prioritizing learning over traditional roles like marriage.

Marguerite of Navarre (1492-1549)

Marguerite of Navarre, a prominent figure of the French Renaissance, distinguished herself as a significant literary voice. Despite not being the sole educated woman to engage in verse during this era, she stood out as the first noblewoman in France to have a multitude of works published. Part of the influential House of Valois, she held familial ties to Francis I, the King of France from 1515 to 1547, and was wed to Henry II of Navarre. Alongside her literary prowess, Marguerite embraced Renaissance humanism akin to Isotta Nogarola and showcased her writing talent reminiscent of Christine de Pizan.

Initially known as Marguerite of Angoulême, she was born to Charles de Valois-Orléans, the Count of Angoulême, and Louise de Savoie. Despite the limitations imposed by her gender on ascending the French throne, being perceived mainly as a pawn for strategic marriages, Marguerite wielded substantial political influence from a young age. Rejecting a proposal from Henry VII of England, she entered a union with Charles, Duke of Alencon in 1509 to resolve regional disputes in southwest France. While Charles did not match her intellect, Marguerite, well-educated by her mother and tutors, saw the marriage as beneficial for her brother’s rule.

Following Francis’s capture post the Battle of Pavia in 1525, Marguerite adeptly negotiated for his release with the Hapsburg emperor Charles V. This diplomatic feat, known as The Ladies Peace, was sealed during a private meeting between Marguerite and Charles V, overseen by a female companion for decorum. Tragically, her husband succumbed to battle wounds, leading her to later marry Henry, King of Navarre, in 1527. Their daughter Jeanne, raised with the same educational rigor as Marguerite, would eventually become the mother of Henry IV of France, securing Marguerite’s legacy as a matriarch of intellect and influence in Renaissance France.

Humanism and Catholic Reform

Marguerite, a proponent of Humanism, immersed herself in studying scripture, diverging from traditional beliefs by emphasizing the importance of sincere faith and genuine repentance over religious rituals for eternal salvation. Despite facing opposition for her unorthodox views within the court and the University of Paris, her social status shielded her from severe repercussions, allowing her to indulge in forbidden texts without consequence.

Her literary endeavors, particularly the posthumously published Heptaméron (1558–59), echo the narrative style of Boccaccio’s Decameron. This collection of 72 tales, intended to reach 100, showcases women engaging in debates on contemporary societal issues, notably the gender disparities prevalent in the 16th century. Marguerite’s true literary prowess, however, was fully recognized in the late 19th century upon the discovery of her unpublished works, elevating her status as a significant figure in literature. Scholars today acknowledge her substantial impact on the literary landscape through the profound exploration of historical, philosophical, and religious themes in her writings.

Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589)

Catherine de’ Medici, renowned as the queen consort of Henry II of France during his reign from 1547 to 1559, later assumed the role of regent of France from 1550 to 1574 on behalf of her young son. The mother of three French kings—Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III—she emerges as one of the most commanding figures of the period, deeply intertwined with the infamous Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Day in 1572.

Hailing from Florence, Italy, Catherine was born in 1519 to Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici, Duke of Urbino, and ruler of Florence (to whom Machiavelli’s The Prince was dedicated), as well as Madeleine de La Tour d’Auvergne, a scion of the French noble house that would later evolve into the royal House of Bourbon. The matrimonial alliance between the young Catherine and her husband was a strategic move within the broader framework of the French-Italian collaboration against the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.

Tragedy struck early in Catherine’s life, as both her parents passed away shortly after her birth. Raised under the care and tutelage of relatives and nuns in Florence and Rome, she matured amidst a blend of Italian and French influences. At the tender age of 14, in 1533, she entered into matrimony with Henry of the House of Valois, Duke of Orléans, and the second son of Francis I of France. Subsequent to the demise of Henry’s elder brother, he ascended as the heir to the French throne and was ultimately crowned as the king of France in 1547, solidifying Catherine’s position as queen consort.

Queen Regent

Catherine’s marriage to Henry was far from blissful. Struggling to produce an heir, she finally gave birth to a son, Francis, at the age of 34. Throughout their marriage, Henry openly pursued relationships with mistresses, notably Diane de Poitiers, who was gifted Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley until Catherine intervened and expelled her. The French courtiers disparagingly referred to Catherine as a ‘merchant’s daughter,’ highlighting her non-aristocratic background.

Despite Catherine bearing ten children, only seven survived into adulthood, with the others plagued by various health issues. Henry’s untimely death in a jousting accident in 1559 led to the ascent of their son Francis II to the throne, a young and frail king influenced by the powerful House of Guise.

Francis II’s reign was short-lived, lasting only 16 months due to his fragile health. After his passing, his brother Charles IX, a mere 10-year-old, took the throne. During Charles IX’s reign, Catherine, the Italian-born ‘merchant’s daughter,’ assumed the role of queen regent of France, strategically seizing power from the Guise family. Her tenure as Queen Regent spanned three decades, as Charles IX died childless, paving the way for his brother Henry III to succeed him.

The French War of Religions

The French War of Religions was a significant crisis during her reign, as France grappled with a religious civil war between Catholics and Huguenots (French Protestants). In the 16th century, a growing number of French citizens converted to Protestantism and joined the Reformed Church of France, leading to tensions between the two religious groups. Initially, Huguenots were treated with tolerance, but this shifted towards hostility over time.

Catherine de’ Medici approached the conflict primarily as a political issue, overlooking the underlying societal divisions in France. In 1562, she attempted to address the situation by issuing the Edict of January, advocating for tolerance towards the Huguenots. However, this move displeased devout Catholics, who then sided with the House of Guise, viewing them as defenders of their faith.

Subsequently, Catherine orchestrated the marriage between her daughter Marguerite and the Protestant Henry, King of Navarre, who later became Henry IV of France and was crowned in 1589.

St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre

The Guises had conspired to assassinate the Huguenot leader, Admiral Gaspard II de Coligny, with approval from King Charles IX and his mother, Catherine de’ Medici, who feared Coligny’s influence. The initial plot failed, but the admiral was eventually killed in a second assassination attempt on August 24, 1572, during the royal wedding in Paris. This act, known as the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, triggered widespread Catholic violence. Numerous Huguenots, including those who had come to Paris for the wedding festivities, were slaughtered by Catholics. Despite a royal order to stop the killings, the massacre persisted and expanded beyond Paris into the provinces.

Detail from Un matin devant la porte du Louvre (One morning at the gates of the Louvre) by Edouard Debat-Ponsan (1880). The painting depicts Catherine de’ Medici (in black) viewing the bodies of victims of the 1572 St Bartholomew’s Day massacre. Photo source.

In the aftermath, Catherine struggled to maintain unity in the kingdom but faced ongoing challenges. Her death in 1589 left her despised by Protestants and the civil war unresolved. Henry IV of France, her son-in-law, eventually brought an end to the conflict, converting to Catholicism and issuing the Edict of Nantes in 1598. This edict granted religious freedoms to Protestants, effectively concluding the religious wars. While history often portrays Catherine as a scheming matriarch akin to Machiavelli, it raises an interesting perspective to ponder how her legacy might have differed if she had been a man.

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625)

Sofonisba Anguissola, hailing from a minor noble family in Cremona, defied the gender norms of her time to become a renowned Renaissance painter. Despite the societal barriers that restricted women from significant artistic pursuits, Sofonisba’s talent and determination propelled her to establish herself as a formidable artist during an era dominated by male painters like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. While male painters like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo are typically the first to come to mind when thinking of Renaissance painters, Sofonisba Anguissola’s achievements stand out as she navigated a male-dominated field with skill and perseverance.

Due to the limitations imposed by her gender, Sofonisba faced obstacles such as the inability to hire male models, which hindered her from creating religious paintings that held the highest prestige in the art world. Consequently, she focused her efforts on portrait painting, a genre in which she excelled and gained recognition not only in Italy but also on an international scale. Sofonisba’s dedication to her craft and her ability to excel in the realm of portrait painting despite societal constraints underscore her resilience and artistic prowess.

Being named after a Carthaginian noblewoman, Sofonisba was the eldest of seven siblings, including six sisters. Her early artistic education was unconventional for a woman of her time, as she and her sister, Elena, boarded with Bernardino Campi, a prominent local painter, for training. Even after Campi’s relocation to Milan, Sofonisba continued her artistic pursuits under the tutelage of Bernardino Gatti, demonstrating a relentless commitment to honing her skills. Notably, her correspondence with the renowned Michelangelo further showcases her passion for art and her eagerness to learn from the masters of the era.

A Painter for the Spanish Court

Her talent blossomed as she began to earn a livelihood through her portraiture. Despite losing many of her artworks in a fire, around 30 of Sofonisba Anguissola’s paintings, including the notable self-portrait mentioned earlier, have endured through the centuries.

Word of her skill transcended Italy, leading to an esteemed invitation in 1559 to the court of Philip II of Spain in Madrid. There, she not only served as a tutor to Queen Elizabeth of Valois, Philip’s third wife, but also as the court painter.

For fourteen years, Sofonisba thrived at the Spanish court under the king’s financial patronage. Philip II even facilitated her marriage to a Sicilian nobleman, Fabrizio de Moncada, by providing her dowry and a substantial pension.

Following the death of her first husband in 1579, Sofonisba remarried and used her personal wealth to support her prolific painting career and become a prominent arts patron. Among her many pupils was the renowned Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck, who sought her guidance on portraiture during his visit to her in 1624.

Today, Sofonisba Anguissola is recognized as a paramount figure in late Renaissance painting. Giorgio Vasari captured her essence aptly by praising her exceptional dedication and skill, declaring her unmatched by any woman of her time in drawing, coloring, and painting from life with grace and excellence.

Click the links to see further information, or check out Renaissance People: Lives that Shaped the Modern Age written by Robert C. Davis and Beth Lindsmith (Thames & Hudson, 2019) and which was used as a starting point for this article.

Our previous article “Five Female Explorers” may also be of interest, as well as:

Many of our participants in Odyssey Traveller are women, either travelling alone or with a companion. Check out our tours and travel anywhere in the whole world with Odyssey.

The following tours have special focus on the Renaissance:

- Living in the Renaissance City of Florence (22 days, based in Florence, Italy)

- Renaissance Italy, story of five families (21 days, focused on the Medicis of Florence, the Montefeltros of Urbino, the Estes of Ferrara, the Gonzagos of Mantua, and the Sforzas of Milan)

You may also want to sign up for our Summer School classes, held for seven days in January 2020 in Hobart to discover more about the splendour of this time period:

All of the tours organised by Odyssey Traveller travel in small groups and are especially designed for the mature-aged traveller.

Articles about Italy published by Odyssey Traveller

- Italian Renaissance Families: Ferrara and the Este

- Italian Renaissance Families: Mantua and the Gonzaga

- Italian Renaissance Families: Urbino and the Mentefeltro

- The Roman Empire

- Who were the Roman Emperors

- Questions About Italy

- Trip Advice for Travellers going to Italy

- 10 Great Books to Read Before You Visit Italy

- as well as more articles on Italy here

External articles to assist you on your visit to Italy

Related Tours

18 days

Aug, SepArt and History of Italy | Small Group Tour for seniors

Visiting Italy

Taken as a whole, Italian Civilization (which includes, of course, the splendid inheritance of Ancient Rome) is absolutely foundational to Western culture. Music, Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Literature, Philosophy, Law and Politics all derive from Italy or were adapted and transformed through the medium of Italy.

From A$16,695 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Apr, Aug, MayRenaissance Italy Tour: Story of Five Families

Visiting Italy

Explore Renaissance Italy on this small group tour though an examination of five significant city states. Florence, Urbino, Ferrara, Mantua and Milan were all dominated by families determined to increase the status of their city through art and architecture. Spend time coming to know the men and women who helped create the cities, as well as the magnificent legacy they left behind.

From A$14,295 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Mar, Sep, MayFlorence: Living in a Renaissance City

Visiting Italy

A small group tour with like minded people, couples or solo travellers, that is based in Florence. An authentic experience of living in this Renaissance city The daily itineraries draw on local guides to share their knowledge on this unique European tour. Trips to Vinci, Sienna and San Gimignano are included.

From A$14,375 AUD

View Tour

21 days

May, Aug, SepHabsburg Spain vs Tudor England: small group tour exploring 16th century history of England & Spain

Visiting England

This holiday with a leading tour operator allows the escorted tour for seniors to explore the life and times of the royal families responsible for making England and Spain so significant in the 16th century with local guides providing the travel experience for the detailed itineraries. We spend 10 days travelling from London to Madrid.

From A$14,295 AUD

View Tour