History of Wales: The Definitive Guide for Senior Travellers

History of Wales The Anglo-Saxons fell to the Normans in 1066, but it would take more than two centuries before England’s rulers–starting, crucially, with Edward I–turned their attention to dominating Wales. In this article, we…

17 Oct 19 · 11 mins read

History of Wales

The Anglo-Saxons fell to the Normans in 1066, but it would take more than two centuries before England’s rulers–starting, crucially, with Edward I–turned their attention to dominating Wales. In this article, we will look at the complex and dramatic history of Wales covering the period from the 1066 Battle of Hastings to the 1536 and 1543 Acts of Union.

“Pure Wales”

“Wales” and “Welsh” were names imposed by the invaders. According to Jon Gower in his book The Story of Wales (Penguin Random House, 2012), the terms come from Old English and translates to “foreign land” and “foreigners”. As Gower says, “The Welsh had their own name for themselves, the Cymry“–derived from the Celtic which means “fellow countryman”–“but it was the Norman label that stuck in the end” (p. 83).

The Normans were descended from the Vikings who had settled in the area of what would become Normandy (northern France). Norman historians claim that in the mid-11th century, Duke William of Normandy visited his cousin, the childless Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor, who promised him the throne. When Edward reneged on his promise on his deathbed, William challenged the new king Harold II and emerged victorious at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. William was now king of “Angle-land”, or England.

Before the Normans came, Wales had enjoyed a cultural and political autonomy ever since the 8th century Offa’s Dyke geographically separated the Britons of the west (Wales) from the Germanic tribes of the east (England). By 1066, Wales itself was divided into several kingdoms: Powys, Gwynedd, Seisyllwg, Dyfed, Brycheiniog, Morgannwg and Gwent. These kingdoms were headed by local rulers, who re-drew territories through intermarriage and conquests. Northwest Wales was also still fighting off Viking raids well into the 11th century.

The presence of the Welsh rulers, the Vikings, the mountainous terrain of the land, and the fact that the Normans and the succeeding Angevin kings spent more time abroad than in England (for example, the Angevin king Richard spent only 10 months of a 10-year reign in England) kept Wales largely out of the English grip.

That is not to say that there were zero Norman incursions into Wales. On the contrary, many Norman barons who were not given the best parcels of land by William (who of course redistributed the largest Anglo-Saxon lands to himself and his closest followers–you can read more in our article here) moved into Wales, grabbing land often without the crown’s consent in order to establish their own estates.

Called the “Marcher lords”, they were tasked to secure the English border from Welsh leaders, but were not beholden to the laws of the crown. They followed their own laws and customs, built their own castles, and passed the land to their descendants. By the 1100s, Wales was divided into two regions: Pura Wallia (“pure Wales”), held by the Welsh rulers, and Marchia Wallia (the Welsh Marshes), held by the Marcher lords.

The Princes of Wales

In 1205, Llewelyn ap Iorwerth of Gwynedd married Joan, the illegitimate daughter of King John of England (ruled 1199-1216).

(A quick note about the ancient Welsh naming convention before we continue. This naming convention is patronymic, which means sons are given the surname of their father’s given name. “Ap” or “Ab” is a contraction of the Welsh word mab, “son”. Llewelyn ap Iorwerth then means, “Llewelyn, son of Iorwerth”. Modern Welsh surnames derive from this contraction and from Anglicisation–for example, Price would have been “ap Rhys”, or son of Ryhs).

Llewelyn expanded his territory, making Gwynedd a formidable kingdom in Pura Wallia. When Llewelyn started encroaching English lands, John sent troops into Gwynedd. Llewelyn retaliated by forging alliances with John’s rival barons, which influenced John’s signing of the Magna Carta (Great Charter) in order to make peace and end the baronial revolt. (Joan might have also played a role to forge peace between her father and her husband.)

In 1216, Llewelyn was recognised as overlord by the other Welsh rulers, and in 1218 he was acknowledged by the English crown. Hailed as Llewelyn the Great, he was largely unchallenged until his death in 1240. He is described in Welsh chronicles as the “Prince of Wales”, and the kingdom he left behind had the potential of forming a truly independent Wales.

His grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, referred to himself as “Prince of Wales” as well, but he wanted to make the title a reality. This meant marching into Marchia Wallia and subduing the Marcher lords. Like his grandfather, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd allied himself with the baronial opponents of Henry III (ruled 1216-1272), who had ascended the throne at the age of nine after John’s death.

The second baronial revolt ensued. When Henry’s chief baronial opponent, the 6th Earl of Leicester Simon de Montfort, was killed in 1265, Llywelyn changed tactics. Three years after Simon de Montfort’s death, Llywelyn signed a treaty recognising Henry III as his overlord. The King of England, in turn, recognised Llywelyn as Prince of Wales.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd–also called Llywelyn the Last–would be the last sovereign Prince of Wales before English conquest.

Edward I Goes to War

Not all of the smaller lords, including Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd and Gwenwynwyn of Powys, were happy with the treaty. Henry III’s successor, Edward I, also did not like the Prince of Wales. When Llwelyn ap Gruffudd expressed intention to marry Eleanor, Simon de Montfort’s widow, Edward I responded in anger, believing that the Prince of Wales simply wanted to start another baronial revolt against England.

In 1274, Dafydd and Gwenwynwyn defected to England. A year later, Edward I had Eleanor kidnapped, and demanded that Llywelyn ap Gruffudd pay homage to him as king. Llywelyn refused, and Edward called him a rebel and declared war.

Edward mobilised the Marcher lords and gathered a huge army to go to war against the Prince of Wales. The campaign lasted a year, and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was forced to capitulate after English forces took Anglesey, Gwynedd’s breadbasket, thereby starving the Welsh.

Llywelyn was later allowed to marry Eleanor (with Edward paying for the wedding feast), and he kept his title as “Prince of Wales” (Gower, 2012, p. 118). The title was on paper only, however. He lost lands, paid a fine “for disobedience” (p. 118), and could only sit back and watch while Edward built his castles on Welsh territory.

In 1282, the disillusioned Dafydd switched loyalties after his brother’s defeat and attacked the English-owned Hawarden castle (p. 119). Edward responded with further invasion, leading to Llwelyn’s death and Dafydd’s execution.

English Domination

In 1284, England annexed Wales under the Statute of Wales, turning it into an English colony. Edward I instituted the royal tradition of giving the title “Prince of Wales” to the heir apparent to the English throne, beginning with his son, the future Edward II, thereby extinguishing Welsh sovereign rule.

Edward I had castles built to guard his new territories, but to also clearly communicate the power of the new rulers. The grandest of these castles, designed with the help of Edward’s military architect, Master James of St George, was Caernarfon Castle.

Caernarfon Castle was built on the shoreline, consisting of a castle, town walls, and a quay all built at the same time. The massive project took 47 years to complete. Historians say the walls of Caernarfon reflect the design of the walls of Constantinople, hearkening back to a Roman past that the British isles shared before the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, and announcing the domination of the English rulers.

And who would pay for Edward’s expensive castles? The English king raised taxes 600 percent, crippling the Welsh lower classes most of all, and taxed the Church of Wales for the very first time (Gower, 2012, p. 125). Oppression of the Welsh continued with the passing of new laws that denied the Welsh the right to buy property within the walled towns (p. 124), and giving the English settlers better treatment by way of lower tax and rental rates (p. 125).

Resistance within Wales continued, led by members of the old Welsh royals stripped of their power, and by the Marcher barons who revolted against Edward II and Edward III. The revolts all failed, and the 14th century brought with it a new threat to the Welsh.

The Black Death

In a previous article (“Britain; The First Industrial Nation“) we wrote about how in the early 1340s, rumours of a “Great Pestilence” devastating Asia circulated among Europeans, until the rumour became reality with the arrival of 12 ships from the Black Sea at the Sicilian port of Messina in October 1347. Most of the sailors aboard the 12 ships were dead; those still living were covered in boils. Sicily turned the ships away, but it was too late.

Historians believe the Black Death was brought by the bubonic plague (though this is still being debated) which we now know is spread by a germ called Yersina pestis that could be transmitted through the air or through the bite of infected rats. Medieval Europe knew little about disease transmission and had no means to stop it. The Black Death would reach London by 1348, and the next year would ravage Wales. The Welsh called it Y Farwolaeth Fawr, the Great Mortality (Gower, 2012, p. 128), killing a quarter of the population in just two years.

Emerging from these years of death and turmoil was Wales’ one final attempt to overthrow the English.

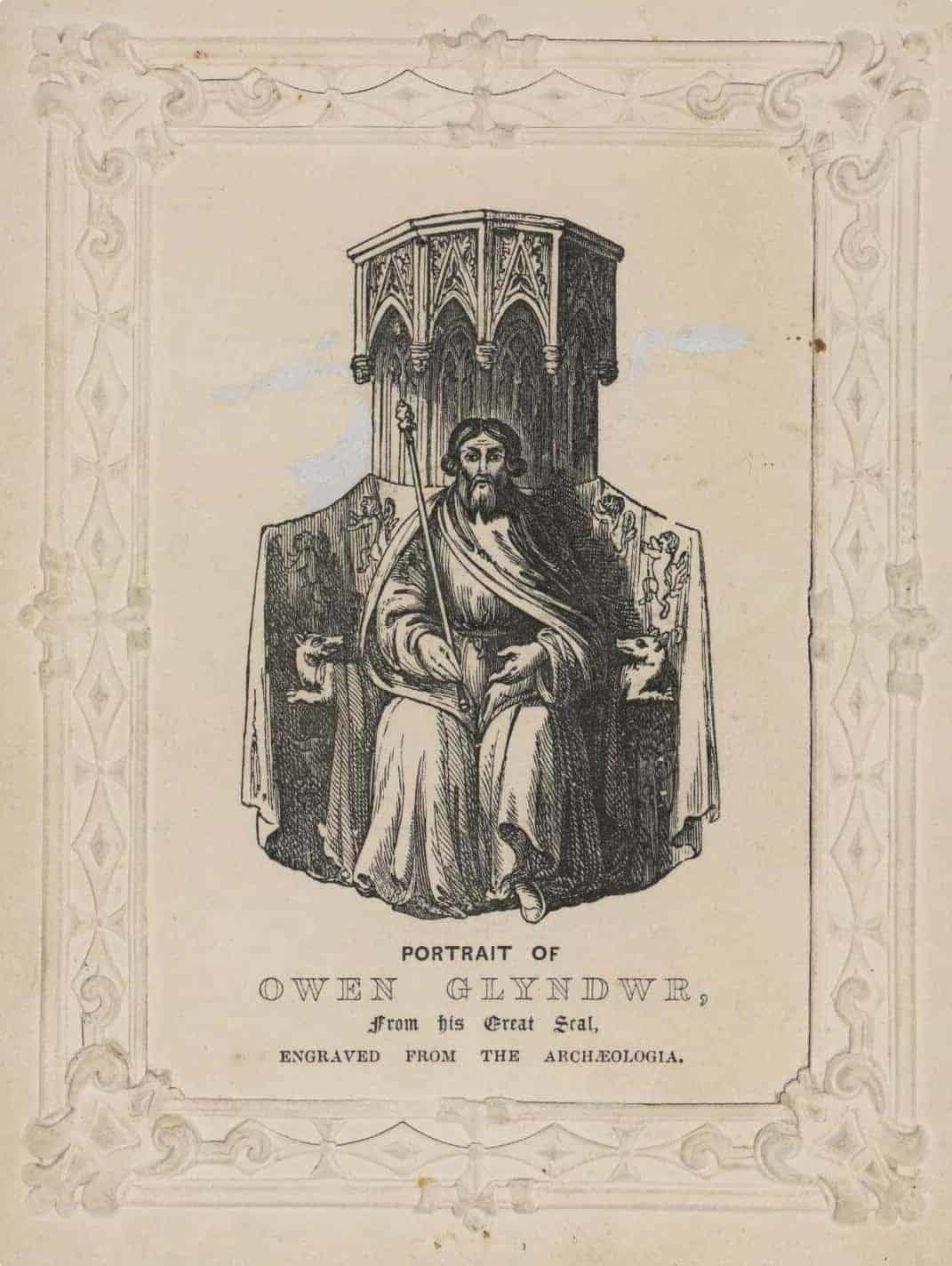

Owain Glyndwyr

Owain Glyndwyr (also spelled Owain Glyn Dŵr or Owen Glendower), a descendant of the princes of Powys, once fought under the banner of the English crown but later instigated an open revolt for Welsh independence.

Born in 1359, he became a ward of the Anglo-Welsh judge Sir David Hanmer after the death of his father. He followed in the footsteps of his foster parent and studied law in London. He was, to quote BBC Wales, “the epitome of an assimilated Welshman”, enlisting for military service under a March lord and fighting for Richard II in Scotland and in France. He later married Hanmer’s daughter and settled in Wales, living a comfortable and prosperous life.

What may have planted the seeds of rebellion in Owain’s heart was a king’s refusal to mediate a land dispute, and the insult he received from the English Crown he once defended on the battlefield. In 1399, Richard II was usurped by a formerly exiled baron, Henry Bolingbroke, who then crowned himself Henry IV. At around the same time, Owain had a land feud with a neighbour, Reginald Grey, Lord of Ruthin. Owain requested arbitration to end the feud that was becoming violent, but the new king refused to arbitrate, even dismissing the dispute with the words “What care we for these barefoot rascals?” (Gower, 2012, p. 136).

Owain, proud of his Powys heritage, did not take this kindly. Now over 40, he called for open revolt, and received support from other Welshmen who proclaimed him “Prince of Wales”.

The revolt did not the succeed, with the final battles fought in 1412. To this day, little is known of what happened to Owain. Some say he might have died on his daughter’s estate in 1421.

Owain became a figurehead of Welsh nationalism, and a figure in popular culture, appearing in pub and street names (and rugby matches against the English).

House of Tudor

About 70 years after Owain’s rebellion, a man of Welsh descent ascended the throne of England and established a dynasty that would rule the kingdom for more than a hundred years.

Henry Tudor, son of the earl of Richmond, could trace his lineage back to Wales. Tudur was one of the sons of Ednyfed Fychan, a military leader who served Llewelyn the Great; Tudur’s son Maredudd was the ancestor of the royal Tudor line. It was Maredudd’s son, Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur, who Anglicized the surname to “Tudor” (Gower, 2012, p. 148).

Owain, now styled “Owen Tudor”, served with the kings Henry V and Henry VI and fought on the side of the House of Lancaster in the Wars of the Roses. The dynastic war, which lasted 30 years, is named after the badges of the opposing houses: white rose for the House of York, and red rose for the House of Lancaster. Owen married Henry V’s widow, Catherine of Valois, and their eldest son, Edmund, was Henry Tudor’s father. Henry had a distant claim to the throne through his mother, the Lady Margaret, great-granddaughter of Edward III’s son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster of the House of Lancaster.

When Henry Tudor was born, his father had already died and the Lady Margaret was only 14, so he was brought up by his uncle, Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke. Yorkist victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury pushed Jasper to move Henry out of England and into France. Henry at this point was the only surviving male heir with any ancestral claim (no matter how distant) to the throne, but the House of York was so stable that it was possible he would just live the rest of his life in exile.

But a sudden split within the House of York splintered the support for Richard III, the third Yorkist King of England. He would also be the last. Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth on August 22, 1485, and he was crowned Henry VII. The following year, he married Elizabeth of York, finally uniting the two warring houses.

The Welsh saw Henry VII’s coronation as a Welsh victory, and the Welsh indeed found favour in London (Gower, 2012, p. 152). But ultimately, English domination remained.

Acts of Union

The 1530s was a crucial decade. Henry VIII’s separation from the papacy and the Roman Catholic Church devastated Catholic Wales, and led to the destruction of Welsh monasteries. Historian John Davies says this move was part of Henry VIII’s “determination to intensify the sovereignty of the crown throughout his kingdom. His policy towards Wales…was part of the same intention.”

In 1536, he enacted a measure that was later clarified in 1543; together they were called the “Acts of Union”. The main effect of the first measure was the division of the March into seven counties or “shires”–Denbigh, Flint, Montgomery, Radnor, Brecon, Monmouth, Glamorgan and Pembroke–which dramatically changed the map and territories of Wales. The March was no longer an independent country; it now clearly belonged to the realm of the English crown.

The law of England was to be the only law, and English–not Welsh–was to be the only language of the courts.

If you want to learn more, we recommend Jon Gower’s The Story of Wales (Penguin Random House, 2012), as well as the many resources linked throughout this article.

The steepest street in the world is in Wales

On a lighter note, a street in north Wales has taken the world record as the steepest in the world. Ffordd Pen Llech in Harlech, Gwynedd has been verified to have a gradient of 37.45% in July 2019 by the Guinness Book of World Records, beating out Baldwin Street in Dunedin, New Zealand (35% gradient). Simon Usborne, writing for the Financial Times, reports on how the record has affected the town, from 13 out of 16 properties on the “steepest street in the world” turning into holiday homes, to gift shop owners churning out “steepest street” keyrings and magnets for tourists. The street has no blueprint; it was believed Ffordd Pen Llech evolved from a footpath and has been in existence for more than 1,000 years. As we have mentioned earlier, Gwynedd was an important kingdom in Pura Wallia.

See this report from The Guardian below:

The street is also near Snowdonia National Park, which Odyssey Traveller visits on its tours in the region. Odyssey Traveller organises a walking tour of Wales, as well as other tours of the British Isles that include visits to Wales. Odyssey’s small group tours are fully escorted–accompanied for the whole tour by an Odyssey Program Leader with local guides–and are especially designed for senior travellers.

Just click through to see the full itineraries and sign up!

Originally published July 20, 2019.

Updated on October 17, 2019.

Articles on Wales published by Odyssey Traveller.

- Questions About Wales

- Snowdonia National Park, Wales

- Millennium Coastal Path, Wales

- Caernarfon Castle, Wales

- Venta Silurum of Roman Wales

External articles to assist you on your visit to Wales.

Related Tours

13 days

AugExploring Wales on foot : small group walking tours for seniors

Visiting Wales

A Walking tour of Wales with spectacular views across as you walk the millennial path across the Irish sea or up in Snowdonia national park. This guided tour that provides insight into the history of each castle visited and breathtaking scenery enjoyed before exploring the capital of Wales, Cardiff with day tours of Wales from Cardiff. For seniors, couples or Solo interested in small groups.

From A$11,895 AUD

View Tour

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$17,860 AUD

View Tour

20 days

May, Sep, JunWalking Ancient Britain

Visiting England

A walking tour of England & the border of Wales. Explore on foot UNESCO World Heritage sites, Neolithic, Bronze age and Roman landscapes and the occasional Norman castle on your journey. Your tour director and tour guide walk you through the Brecon beacons, the Cotswolds and Welsh borders on this small group tour.

From A$13,995 AUD

View Tour