Conserving Versailles: The Definitive Guide for travellers

Conserving Versailles Versailles was the official royal residence for over a century from 1682 – 1789. The splendor of the palace and the hundreds of people living there is awe-inspiring to reflect on. However, at…

9 Aug 19 · 10 mins read

Conserving Versailles

Versailles was the official royal residence for over a century from 1682 – 1789. The splendor of the palace and the hundreds of people living there is awe-inspiring to reflect on. However, at the time, the French citizens who did not live in the king’s world, looked on with contempt. While the French monarchy impressed each other and their international noble networks of their extravagant wardrobe and parties, the people were angered that they could barely afford to feed themselves. On October 5, just before midnight, mere days after the palace held another overindulgent banquet for 200 people, a group of discontented citizens stormed the palace. This event has also been known as ‘The Women’s March on Versailles’ because the group was a majority women. The women forced the royal family to return to Paris and stand trial. This was the last day that Versailles was the official royal residence and the start of Versailles’ slow decline, before it was restored by two amazing curators: Pierre de Nolhac and Gerald Van der Kemp.

But how did Versailles make such a triumphant return from its darkest days to one of the largest tourist attractions in the world? This article will provided a short overview of the history of conservation at Versailles, from the start of the French Revolution in 1789 to today. It will also highlight some of the key obstacles that were overcome to ensure its survival, as well as some key dates in history that have occurred at Versailles in the time following 1789.

Versailles after 1789

Surprisingly, the Château de Versailles was largely left in tact throughout the French Revolution, despite its being symbolic of the frivolous French monarchy that the citizens rebelled against. Tours continued to be taken throughout the grounds, still, without the money to maintain the building it largely fell into disrepair for nearly a century. Many artifacts and furniture were sold, and important artworks, most notably the Mona Lisa, were moved to the Louvre museum, established 1793, as well as private collections. The remainder of the artwork not sold was later joined by works confiscated by the government from convicts, migrants, and religious institutions (Château de Versailles), as it was used as a storage facility for the local government. Yet, it was a waste to let the palace and the stored artworks completely fall into disarray and some saw the potential for the palace to restore its image by becoming a museum. The first museum was opened in 1796, which a year later became the Special Museum of the French School. Then in 1837, King Louis Philippe completely redesigned the palace with a €20 million renovation, to create a full history museum commemorating France’s past from the Middle Ages to 1789. He sought to recast the narrative of the palace from a reminder of royal excess, to a shrine to French history that all citizens could enjoy. Most notably, he commissioned the Gallery of Great Battles, which remains on display to this day.

It was around this time, too, that the Historical Monuments Commission was founded. The goal of the Commission was to preserve important architecture and artwork for future generations. The Commission found it difficult to hit the ground running and had a preference for focusing their attention on Gothic architecture and medieval and renaissance artwork. Based on these criteria, Versailles, with its 17th century architecture and French classical art, was not a priority. However, as the Commission grew, so too did the variety of styles that were preserved. According to Colin Jones, between 1887 and 1920, the number of historical monuments more than doubled (2018, p. 167). This was when the real conservation work on Versailles began.

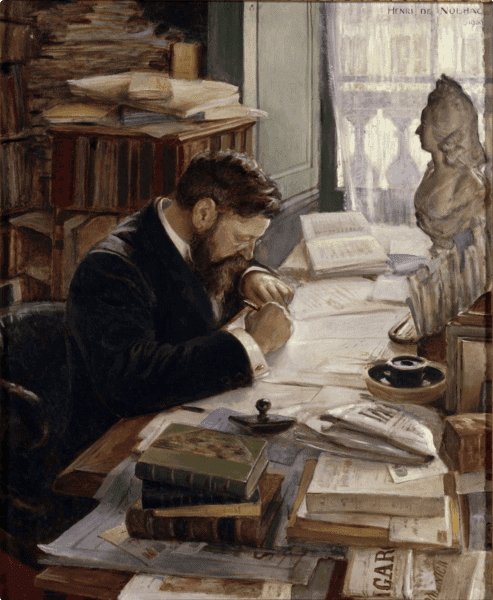

Pierre de Nolhac and his ‘Resurrection’ of Versailles

Pierre de Nolhac, born 15 December 1859, was a poet, historian, academic, as well as a driving force for the conservation of Versailles. After his college studies, de Nolhac attended the Sorbonne to study literature and later attended the French School of Rome, where he wrote a defining thesis on humanism. He first became an assistant curator at Versailles in 1887 on a bit of a whim, after some time spent working at the National Library. In 1892, he became the director of curating at Versailles and set the palace on the path that led to its present representation.

De Nolhac was faced with a number of obstacles on his course to restoring Versailles to what it looked like in it’s heyday. As outlined by Colin Jones in his book Versailles: Landscape of Power and Pleasure, throughout de Nolhac’s time as curator, his main challenges were:

- Lack of financial resources – De Nolhac founded the restoration of Versailles on a network of financial donations. To ease the burden on the French government, who were incapable of providing a large enough budget for all the works to be done to Versailles, de Nolhac focused on sourcing private philanthropy from as many places as he could (Jones 2018 p. 160). One of the major sources of financial support were from American millionaires who had an affliction for the French palace’s grandeur. Several modelled their homes after the palace, for example the Vanderbilts used Versailles as inspiration for their Marble House on Rhode Island, and more recently Trump emulated the Sun King’s decor at the white house with gold curtains and trimmings. Beyond admiring the style, several wealthy Americans contributed to Versailles renovations. Most notably, John D. Rockerfeller donated $1 million, then a further $1.85 million, to restoration projects in France, 75% of which went directly to Versailles, and the remainder to the Chateau Fontainebleu and Reims Cathedral (Jones 2018, p. 169). Other organisations, such as the Amis de Versailles, were also established in support of the palace’s resurrection and upkeep. De Nolhac was a strong, and charming fundraiser, a skill which was similarly reflected in his successor Gerald Van der Kemp.

- Lack of attraction from visitors – In the 18th and 19th centuries, tourism to the palace was targeted at French citizens, as international tourism was not yet a viable market. However, tourism was minimal because French citizens feared that their visiting Versailles would paint them as being sympathetic to the royal family (Jones 2018, p. 164). To counter this, de Nolhac went looking for lesser known artists and portraits of unpopular courtiers to represent life at the time without having visitors focus solely on the monarchs and important public figures, which were the object of hatred.

- Lack of dedication to research and curatorial care – Not only did insufficient funds and visitors negatively impact the ability of de Nolhac to curate Versailles appropriately, but there was also an underlying feeling in the industry that Versailles was best left to waste away gracefully (Jones 2018, p. 159). Before de Nolhac stepped in, the style of curation was to do nothing. But instead of following this style that was recommended to him, he chose to take a scholarly approach, taking the time to uncover the truth about how the royals lived while at the same time correcting the false assumptions about the ancien regime. Based on this approach, he was then able to change the paradigm of Versailles being a monument commemorating the absolutist monarchy to it being an important historical site in all of French history.

Modernisation vs. Historical Accuracy

Of those colleagues who believed that Versailles should not just be left to crumble, the rest believed that curating was intrinsically tied to modernisation and improving the palace to blend with the style of the time. However, de Nolhac opposed this idea and believed that the best way to conserve the palace was for it to be restored to an exact replica of how it looked and was used during the monarchy’s residence there. In other words, he wanted the palace to reassert itself to its ‘initial identity’ (Jones 2018, p. 163). This meant tearing down most of the work that King Louis Phillippe commissioned, which under-represented the monarchy’s influence as a result of the political climate that existed post-revolution. Over approximately 30 years, de Nolhac re-installed the royal apartments and conducted extensive research into the royals’ time at Versailles, so that his successors could pick up where he left off in of refurnishing the palace.

Escaping Destruction during WW1 and WW2

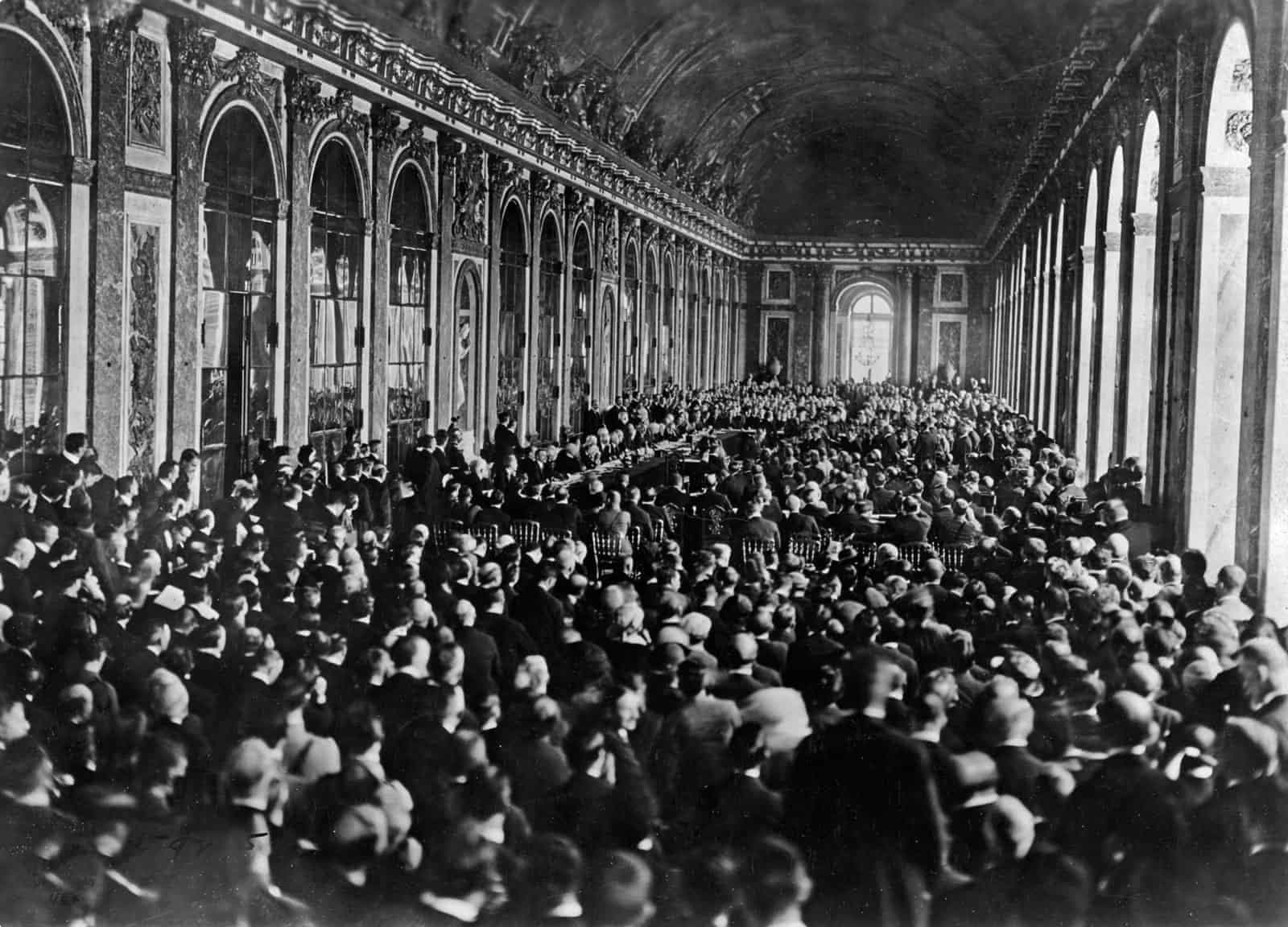

During the first world war, the curatorial staff braced the palace as best they could by relocating and hiding important artwork (Jones 2018, p. 165). But their attentions were drawn toward supporting the war effort, and no maintenance of the grounds were underwent. For the most part Versailles was left intact and unlooted when it reopened after the war. On 28 June 1919, the end of the war was marked in the Hall of Mirrors with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. The Germans, who nearly 50 years prior in the same Hall had first been recognised as a German Empire after the Franco-Prussian war, reluctantly agreed to pay reparations and other consequences to the Allied forces (Kaiser 2009). The signing of the Treaty in Versailles was very important to the conservation of the palace, as it brought the palace back to world’s consciousness, and solidified the shift from an absolutist monarch centre to a symbol of democracy (Jones 2018, p. 165). Thus, Versailles’ reputation would be further disassociated from the royal regime that spent while its people went hungry.

In the interwar period, the Château lacked the resources to resume their restoration work. There was a very small budget from the government and a halt to the number and amount of donations given. In a desperate attempt to continue with conservation, Versailles began charging visitors an entry fee (Jones 2018, p. 168). Conservation continued slowly until WW2 erupted. Versailles had much more to fear from the Germans in this war because it was the site where the Treaty was signed limiting Germany’s powers, and France also took a strong stance in enforcing the articles of the Treaty. The curators reinforced doors, boarded up windows, fireproofed roof rafters, and relocated artwork, among other precautions. They were all but certain that the Germans would retaliate based on how Germans negatively regarded the site (Jones 2018, p. 169). However, again, Versailles was lucky to come out of WW2 relatively unscathed and still in possession of its art.

Gerald Van der Kemp

Born 5 May 1912, Van der Kemp studied at the École des Beaux-Arts for two years before joining the army. He returned to school at the Institute of Arts and Archeology and in 1936 became an assistant curator at the Louvre. Due to his experience with art and the army, when WW2 broke out, he was charged with protecting some of the world’s most important pieces of art. He secreted many pieces away to southern France and was said to have kept the Mona Lisa under his bed so the Nazis’ wouldn’t find it (Jones 2018, p. 173). With a few near-captures, Van der Kemp was successful in safeguarding these pieces and returned them to the Louvre after the war ended. Because of exemplary dedication to protecting art during the war, he was hired as assistant curator at Versailles in 1945. He was then named head curator from 1953 to 1980.

Picking up where Pierre de Nolhac left off, Van der Kemp’s most important curatorial feat was accumulating the original furniture that had been sold off from the time of the French Revolution (Jones 2018, p. 174). Similarly to his predecessor, Van der Kemp was skilled at developing a network of benefactors around the world to contribute to the restoration. He scoured art auctions and petitioned for all works that belonged to Versailles to be returned. He was largely successful, except of course in the case of the Mona Lisa that remains at the Louvre. Van der Kemp was also responsible for improving visitor experience as it was becoming one of the most visited tourist sites in the world. He installed modern toilets and restaurants, as well as allowed for visitors to roam the grounds freely, in contrast to the strict tour rules that had been at the palace previously.

Gerald Van der Kemp is one of the most remembered curators in the world for his work on Versailles. He was also responsible for restoring Monet’s Giverny garden at the request of the Institut de France in 1977. Once again, he reached out to his networks of benefactors to help finance the $2.5 million project (Woo 2002). Overall, his career led to two of the greatest conservation successes of French historical sites. (You can see these both of these sites in person by joining Odyssey Traveller’s escorted trip to the Gardens of Italy and France.)

Versailles has played host to a number of events that shaped our world. For this reason, in addition to its artistic value, it was inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage Listings in 1979. Visitors can fully immerse themselves in a piece of French history, thanks to the curatorial work of Pierre de Nolhac and Gerald Van der Kemp, in addition to the many others who supported their visions. It has now become one of the world’s biggest tourist locations and welcomes approximately 10 million visitors each year. As a result, there are some concerns over what overtourism will mean for the Palace’s conservation. But for now, it remains a beautiful French time capsule.

This article will be published last in a series on Versailles: its construction, its heyday, and its conservation. Check out our previous articles on Versailles: Constructing Versailles, to find out how the palace was established, as well as what life was like Living at Versailles.

About Odyssey Traveller

If you want more first-hand learning about Versailles and its magnificent gardens, join Odyssey Traveller’s escorted trip to the Gardens of Italy and France. On this tour, you will take a day trip form Paris to see the grounds of Versailles and will be able to compare it with some of the best gardens that Italy and France have to offer. Odyssey Traveller’s tours are all designed for the mature or senior traveller, whether travelling alone or with a partner.

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. We specialise in educational small group tours for seniors, typically groups between six to fifteen people from Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada and Britain. Odyssey Traveller has been offering this style of adventure and educational programs since 1983.

We are also pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey Traveller has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey Traveller achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, do visit and explore our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

Related Tours

24 days

Sep, AprLa Belle France small group escorted history tours for seniors

Visiting France

Travelling with like minded people on this small group we visit several culturally significant and picturesque regions of France, including Provence, Champagne, Burgundy, and Bordeaux regions, where we sample wine and learn more about the tradition of wine-making. We also visit the Loire Valley to see its many castles. Finally, we travel to Bayeux, from where we we visit Mont St Michel and spend time up on the Normandy landing beaches with local guides.

From A$19,965 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Mar, SepExplore Paris | 21-day Small Group Tour Exploring Parisian Life

Visiting France

On this small group tour of Paris, travellers take the time to join local guides to learn about the destinations within this city. Authentic experiences with like minded people and an Odyssey tour leader. Staying in apartments this European tour immerses itself in Paris' history, art, and culture in the city of light.

From A$15,325 AUD

View Tour