Terracotta Warriors: History and Latest Discoveries

Travellers flock to Xi’an to walk around Emperor’s Qin’s tomb complex, one of the most famous archaeological finds in the world, the Terracotta Warriors

13 Nov 19 · 9 mins read

Terracotta Warriors: History and Latest Discoveries

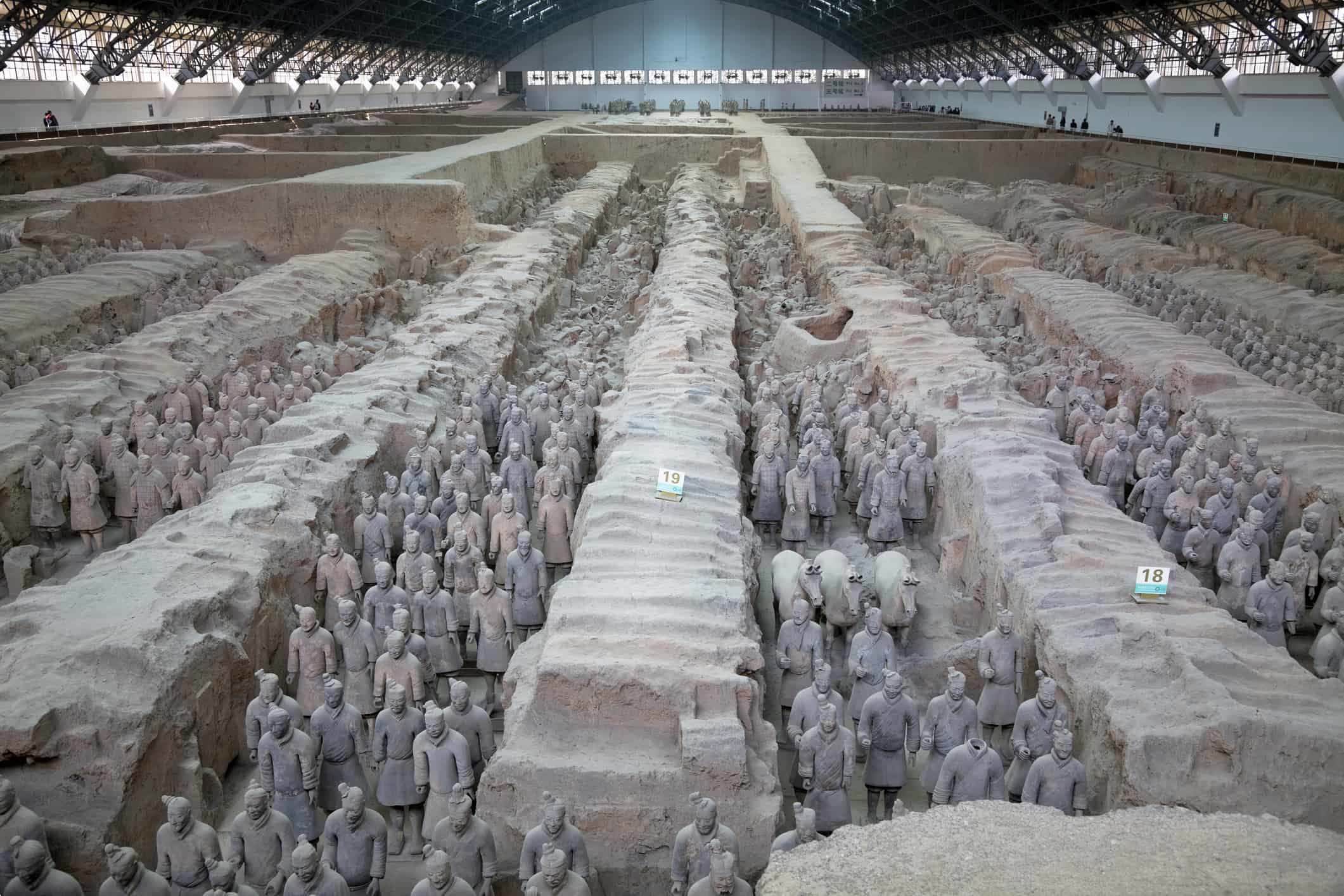

Emperor Qin Shi Huang was the first emperor to rule over a truly unified China. Though his reign was short-lived, lasting only 15 years, his name might just be the most recognisable among China’s emperors for his army of Terracotta Warriors, which guard his tomb. To this day, travellers flock to Xi’an to walk around Emperor’s Qin’s tomb complex, one of the most famous archaeological finds in the world. The underground vault containing the warriors, bronze chariots, and horses was discovered fortuitously in 1974 by workers drilling a well.

In this article, we will look at the history and latest discoveries regarding the mysterious terracotta warriors, including the latest theory that their design might have been influenced by Alexander the Great.

Travel on the Silk Road with Odyssey

This is written as a backgrounder for our small group tours. Odyssey Traveller’s 29-day Silk Road tour begins in Xi’an and takes you on a journey across the Eurasian steppe, tracing the ancient trade routes. The ancient Silk Road facilitated a two-way exchange of goods and ideas and led to the prosperity of cities supplying the routes’ ports and markets of trade. UNESCO has a full list of the Silk Road cities, which includes Guangzhou and Xi’an (China), Isfahan (Iran), Bukhara and Samarkand (Uzbekistan), Jeddah (Saudi Arabia), Baku (Azerbaijan), Almaty (Kazakhstan), and Venice (Italy).

This guided tour will take you to the Silk Road cities and important stops in China, Kyrgyzstan (to reach the Silk Road border post of Naryn), and Uzbekistan and give deeper knowledge of the Silk Road’s incredible legacy. In China, we start in Xi’an, the eastern terminus of the Silk Road and China’s oldest ancient capital, the perfect place from which to commence our tour. It possesses the longest history of any of China’s cities. (You can read more in our article on Xi’an here.) Our tour then takes us to Lanzhou, the capital and largest city of Gansu Province in Northwest China. We venture further west, into the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China. Just click through to see the full itinerary.

The rest of our tours to Asia can be found here, while all of our Asia-related articles can be found here.

Our articles on China include:

- Xi’an the Beginning of the Silk Road

- Silk Road Explorers

- History and Legacy of the Silk Road

- Dinosaurs and Dinosaur Fossils

- The Bund

For more information about the terracotta warriors, we recommend Edward Burman’s Terracotta Warriors: History, Mystery and the Latest Discoveries (Weidenfield & Nicolson, 2019), and the resources we’ve linked in this article.

Before the Qin Dynasty: Shang and Zhou

Before Qin Shi Huang became emperor and unified the empire, China already had a long history.

Shang Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty, which ruled from about 1600 to 1046 BC, was the first Chinese dynasty to leave historical records as Chinese logographic writing and an intricate calendar system were developed during its reign. The dynasty’s territory during this period was concentrated in the North China Plain.

The Shang and Zhou eras were generally called the Bronze Age of China, as bronze (an alloy of copper and tin) played an important role in the state’s material culture.

While Shang architects also worked with other materials such as jade and clay, bronze casting of weapons and ritual objects gained so much prominence and prestige that these treasured objects were often buried with their owners. For example, Fuhao, a consort of a Shang ruler, had a relatively small grave but contained 468 bronze objects, 775 jades, and more than 6,880 cowries. One can just imagine what the bigger graves contained.

We will keep this in mind as we consider that the famed Terracotta Warriors were buried with Emperor Qin.

Zhou Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty was followed by the Zhou Dynasty, whose reign covered eight centuries of Chinese history (1046 BC to 256 BC). The Zhou lived just west of the Shang territory, coexisting with the Shang until the Zhou conquered their rulers in a rebellion. Archaeological findings during this long period showed sculptures of chariots and horsemen. Bronzework, a legacy from the Shang reign, continued and prospered, as was working with jade. Bronze lost its religious qualities but continued to be a symbol of personal status. The Chinese writing system also continued to be refined.

During the Shang dynasty, rulers made animal and human sacrifices, and when powerful nobles died, their wives, servants, bodyguards, and horses were killed and buried alongside them. The Zhou slowly turned away from this custom, and instead substituted clay figures to serve as the companions of the deceased.

The Zhou dynasty began with two centuries of stability, but the dynasty began to fracture. In 771 BC the Zhou nobles split apart into two courts (the Xi or Western, and Dong or Eastern Courts), headed by two princes. Only one survived, and from 770 BC, the dynasty became known as the Dong (Eastern) Zhou Dynasty. Dong Zhou would be further split as its small states continued to fight each other.

Around 221 BC, one of these small kingdoms, the Qin in the mountainous west, conquered the rest of the states and inaugurated a new Chinese dynasty.

Rise and Fall of Emperor Qin

One theory regarding the origin of the country name “China” is that it came from Qin, the first dynasty to unify the empire. Zhao Zheng became leader of the Qin kingdom only at the age of 13 in 246 BC. He and his forces ruthlessly cowed the six remaining kingdoms using “espionage, extensive bribery, and…gifted generals” (Müller, 2019) until he became emperor in 221 BC. As leader of a unified China, he took the name Qin Shi Huang (“First Sovereign Emperor”).

What we know of Emperor Qin we only know from the historical documents of the dynasty that succeeded him, the Han. According to the Han’s court historian, Sima Qian, writing more than a century after Qin’s death, Qin’s short reign was defined by centralisation and control. He standardised coins, weights, and measures, and abolished the old feudal order by forcing aristocrats to uproot themselves from their territories and live close to him in the capital, jade- and gold-rich Xianyang (north of present-day Xi’an). In short, power and definition emanated from the emperor–an administrative structure that would be emulated by succeeding dynasties. The Great Wall, still an enduring monument to power, was also constructed and completed during his reign.

The emperor was painted as a superstitious leader obsessed with finding the elixir of immortality, but Sima Qian also noted that Qin ordered the construction of his mausoleum shortly after taking the throne, preparing for the afterlife while still alive. More than 700,000 labourers worked on the enormous 98-square-kilometre funerary compound. Qin died in 210 BC during a royal inspection tour and was laid to rest in his tomb, at the time still unfinished. His dynasty collapsed shortly after, in 206 BC.

Unearthing the Terracotta Warriors

China as an empire would go through several more centuries of upheaval. Fast-forward to the modern age: in 1974, two farmers digging a well near Xianyang uncovered a life-sized terracotta warrior. Authorities were notified, and before long archaeologists were digging the site, finding one terracotta warrior after another. Each warrior was designed with exquisite detail, showing different facial shapes and expressions, hair styles, uniforms, and ranks.

They were in a uniform grey colour when excavated, but more than 2,000 years ago, according to experts, they would have been painted in colour. The more recent 2009-2011 excavations in Pit 1 have unearthed figures with good colour preservation (see photo inserts in Burman, 2019). The photo below shows recreated terracotta warriors in colour:

Four pits have been excavated to date, with archaeologists estimating that the compound contains 8,000 figures.

- Pit 1: the largest pit, containing the infantry and chariots. Here you’ll find a vanguard of standing archers standing in front of armoured warriors equipped with weapons. Each war chariot is pulled by four terracotta horses

- Pit 2: more warriors and chariots, now accompanied by the cavalry, men riding horses

- Pit 3: the command post, at the centre of which is a grand command chariot

- Pit 4: found empty, probably the unfinished portion of the compound

Qin’s tomb itself is still sealed, though archaeologists have discovered other non-military terracotta figures, such as acrobats and dancers–even civil servants equipped with bamboo tablets.

Edward Burman (2019) in his book Terracotta Warriors: History, Mystery and the Latest Discoveries, asks: Where did the knowledge to create these life-sized warriors come from, since there was no sculptural tradition in China beyond some miniature statues? (p. 152). How could artisans jump from baking small clay objects only a few centimetres in height to firing life-sized figures? Burman shares that, unfortunately, we know next to nothing about the actual planning and production of Qin’s tomb, as Sima Qian, the only historian who presented a detailed account of the emperor, did not even mention the terracotta army (p. 105).

To glean insight into the production of the life-sized figures, experts tried various methods. They looked at the ears, finding that no two ears in their sample size of warriors were the same and which meant the terracotta warriors guarding Qin’s tomb could have been modelled on actual warriors.

Through measurements of the weapons and analysis of the metals’ chemical composition, scientists were able to theorise that the artisans did not work in an assembly line–a la Henry Ford’s car factory where one object could be built by several specialist workers–but in small workshops where artisans worked on weapons from start to finish.

One theory, also outlined by Burman (2019, pp. 153-160), was that the size and design of the warriors could have been influenced by the Greeks, specifically Alexander the Great. Burman quotes Lucas Nickel of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London:

The emphasis on the realistic appearance of the warriors as well as the sheer scale to which the medium was used place the terracotta warriors outside the local tradition and require us to consider an outside stimulus[.]

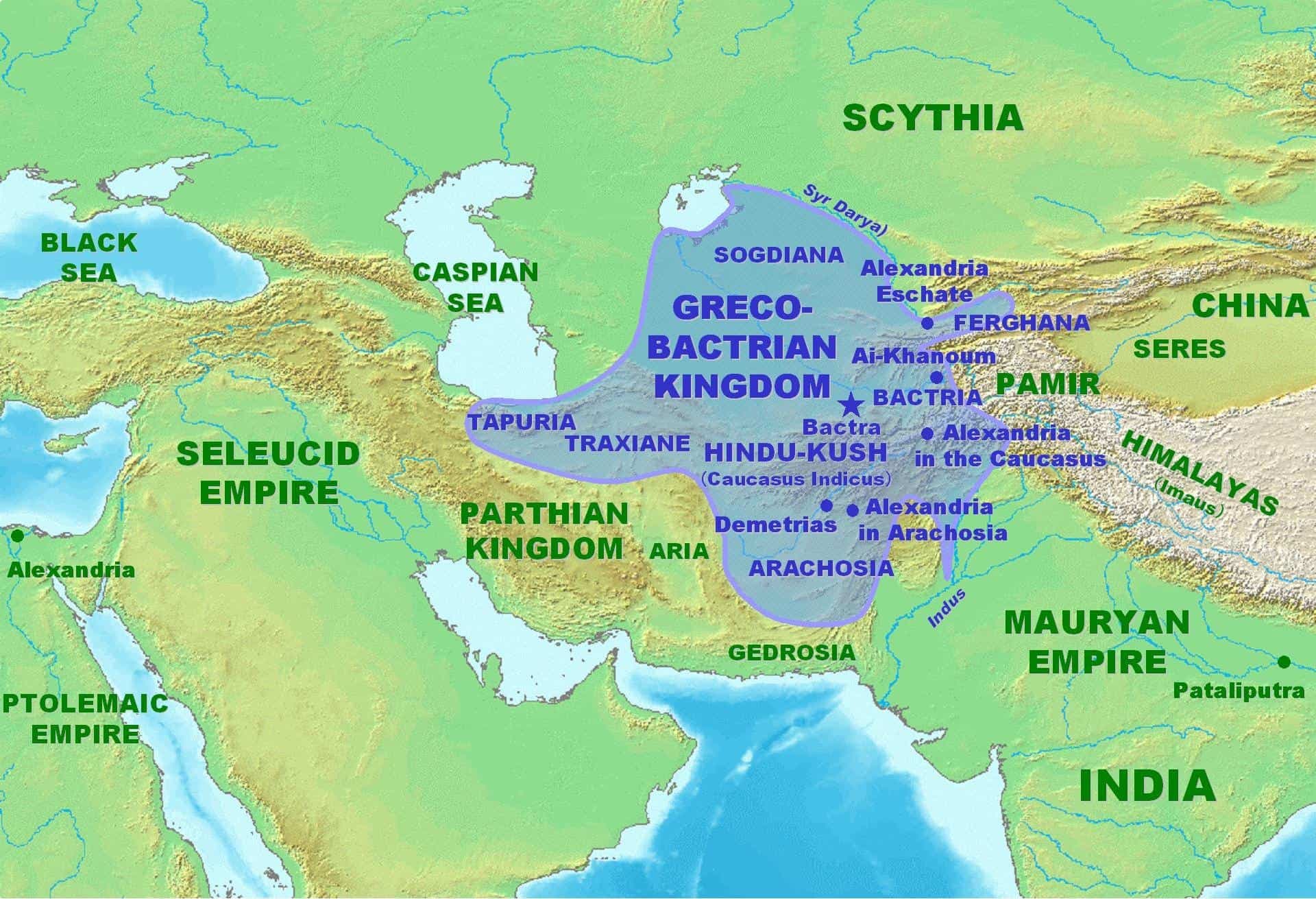

More than a century before Qin unified China, Alexander the Great had conquered his own empire. After his father Philip II was assassinated, 20-year-old Alexander III ascended the throne in 336 BC and immediately planned his conquest of the Persian Empire. Alexander conquered one city after another and faced the Persian emperor Darius III in 333 BC near the town of Issus in what is now Turkey, but that didn’t go well for Darius. The Persian leader fled in haste, even leaving his family behind.

Darius and Alexander would face each other again in 331 BC, but once again Darius would flee, this time to Bactria (which covered present-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan). He wouldn’t be as lucky as the last time. In Bactria, he was believed to have been assassinated by the satrap Bessus. Alexander then got rid of Bessus and conquered the city of Samarkand (Maracanda to the Greeks) in 329 BC and married the Bactrian Roxana in 327 BC.

According to Burman, it is likely that the first real contact between the Chinese and Hellenic cultures began around 250 BC via this Greco-Bactrian kingdom (Burman, 2019, p. 153), an exchange that pre-dated the Silk Road. Previously, we’ve written about the history of the Silk Road, the explorers who dug up treasures from the Silk Road cities, and the history of the Silk Road terminus, Xi’an. Just click through the links to read.

This exchange of knowledge and artefacts would have happened along Xianjiang and Gansu, the latter being the region of the Qin state (p. 156). Gansu was “truly a cultural melting-pot” (p. 157), dominated by the Yuezhi tribe which were pushed west by the Xiongnu, the nomadic tribe that led Qin to erect the Great Wall. The Yuezhi settled in Bactria and themselves became Hellenized. The Yuezhi and other nomadic tribes must have carried to the east reports about Alexander the Great and “Hellenistic statuary” (p. 166), which influenced Chinese sculpture.

Nickel quotes a Sicilian-Greek historian who said “Alexander the Great marked the eastern limits of his empire [with] twelve giant altars representing the twelve major deities of the Greeks” (p. 160). This might have inspired Emperor Qin, as Sima Qian described “twelve metal men” (p. 158) set up in his palace courtyard. These imposing bronze statues were said to have stood 10 to 16 metres in height and were placed at the entrance of the imperial palace (p. 158). The bronze statues were later melted, but they might have led to the creation of the terracotta warriors, which unlike the giant bronze statues survive to this day.

The Qin Dynasty collapsed shortly after Emperor Qin’s death, and Liu Bang, a minor official in the Qin court, swooped in to take the throne. After defeating his rivals, Liu Bang became Emperor Gaozu, marking the beginning of the Han Dynasty’s long rule. Strangely enough, the Han Dynasty stopped commissioning life-sized figures. In a 2018 discovery, ceramic soldiers were found in a Han tomb. They were definitely not life-sized, standing only between 9 and 12 inches (22 and 31 cm) tall. So from life-sized statues, the royals returned to miniatures. One theory suggests that the new rulers did not like the foreign influence introduced by Emperor Qin with his terracotta warriors, and yearned to return to local traditions.

There’s more to learn about Emperor Qin Shi Huang and his terracotta warriors. Once again, we recommend Edward Burman’s Terracotta Warriors: History, Mystery and the Latest Discoveries (Weidenfield & Nicolson, 2019) and the resources we’ve linked in this article. Don’t forget to sign up to Odyssey Traveller’s 29-day Silk Road tour!

Related Tours

29 days

Aug, May, SepTravel on the Silk Road with Odyssey Traveller | Small Group Tour for Seniors

Visiting China, Kyrgyzstan

The Silk Road is an ancient trade route linking China and Imperial Rome through Central Asia. Few areas in the world remain as unexplored or offer such richness in terms of ancient and modern history, culture, and scenic diversity as Central Asia. Our Small group Silk road tours itinerary explores the Road through remote deserts and mountainous environments as we visit key sites between Xi'an and Bukhara.

From A$18,750 AUD

View Tour

12 days

Oct, AprChina Dinosaurs small group escorted palaeontology tours

Visiting China

During our small group Dinosaur Odyssey study program for couples and solo travellers, we will visit two of the most exciting dinosaur sites in China - Zigong Dinosaur Museum. Your program leader will take us to behind-the-scenes places, field studies in the Sichuan Province and Dinosaur Valley, and in the Yunnan Province. Go behind-the-scenes places, field studies at the dig sites, with first-hand experience at palaeontological dinosaur digs.

From A$9,750 AUD

View Tour