Making New Zealand:

Early New Zealand: A Brief History from New Zealand is aptly named as new, as its history is very recent and only dates back a few hundred years. The Maori people were the first to…

23 Apr 19 · 12 mins read

Early New Zealand: A Brief History from

New Zealand is aptly named as new, as its history is very recent and only dates back a few hundred years. The Maori people were the first to arrive from Polynesia in approximately 1200s AD (New Zealand Now); however some historians believe that they arrived much earlier, in the 900s AD. The first Europeans to arrive were the Dutch, led by Abel Tasman, in 1642, who gave the land the name Nieuw Zeeland. After a clash with the Maori people, the crew left a few weeks later, with four men fewer. It wasn’t until the British arrived in 1769 that the Maori were again disrupted. From the moment of Captain’s Cook’s first steps on New Zealand, trade and relations began to blossom, though the land wasn’t claimed as a British colony until the 1840s. But still, the earliest British Governor in New Zealand, entered into an agreement to protect the Maori under the law as equal New Zealand citizens, a precedent set for democracy to follow. These origins are very important to the foundations of New Zealand as a democratic nation.

This purpose of this article will be to look at the history of New Zealand from its first peoples to 1945. It will introduce the foundations within Maori society, and later British colonial society, as well as their collaboration with each other, which culminated to advance New Zealand’s democratic values and social welfare policies and social welfare values. We will end with New Zealand’s involvement in the first and second world wars, which solidified its international image as a democratic and just nation.

The Maori

The Maori say that Polynesian explorer Kupe followed the stars and ocean currents to Aotearoa, now-New Zealand, about a thousand years ago. The beautiful and fertile lands attracted more Polynesian settlers to follow Kupe, who then established tribal societies focused on fishing, hunting native birds, and harvesting local and Polynesian vegetables (New Zealand Tourism). The Maori were prideful and courageous warriors who often warred with neighbouring tribes. Generally speaking, most Maori had, three core beliefs and practices: mana (hierarchical status), tapu (controls on behaviour or implied prohibitions), and utu (revenge to maintain societal balance). Disrespecting these practices would be cause for battle, which is a primary reason that the Maori conflicted with European settlers, who did not abide by the same conventions.

Biculturalism and The Treaty of Waitangi

In 1840, the first governor of New Zealand, William Hobson, sat with Maori chiefs to create a partnership between the Maori and the British Crown. The Treaty was subsequently signed by approximately 500 Maori Chiefs. What the treaty accomplished was, as quoted from New Zealand Now:

- accepting that Maori have the right to organise themselves, protect their way of life and to control the resources they own

- requiring the Government to act reasonably and in good faith toward the Maori

- making the government responsible for helping to address grievances

- establishing equality and the principle that all New Zealanders are equal under the law

This was essential for maintaining peace and creating a unified New Zealand as the population at the time was split nearly 50/50 between Maori and non-Maori populations. However, from the 1860s to the 1890s, the imbalance of the two groups, continued to escalate. According to John Chambers in his book, A Traveller’s History of New Zealand and the South Pacific Islands, depopulation of the Maori people was rampant as a result of a number diseases outbreaks such as measles and tuberculosis (2018, p. 195). Moreover, in the the 1860s to 1880s civil war broke out as a result of land scarcity, as European settlers demanded the Maori sell their land for settlement. This sparked the ‘King Movement‘ in which the Maori tribes elected kings who created judiciary and police organisations to protect their land. Eventually, there was movement toward the establishment of the Young Maori Party, who upheld the Treaty while also entering government positions and advocating for the welfare of Maori communities.

The Young Maori Party

The Young Maori Party was a group of three young men influenced by Sir James Carroll, the first high-ranking Maori political actor. The Party had four main tenets: to improve education and healthcare, promote communal farming, stop Maori land sales, and support chief hierarchy (Chambers 2018, p. 196).

Born 3 July 1874, Apirana Ngata was born to a Maori father and a mother of Scottish descent. He was proud of his heritage and sought to bridge the gap between the Maori and ‘Pakeha’ (Europeans). Ngata trained as a lawyer, but had a passion for social and economic reform for Maori communities. He aligned himself with James Carroll, Liberal minister, for whom he drafted policy that advocated for Maori land rights. His career portfolio included contributions to the Maori Lands Administration Act of 1900, the Maori Councils Act 1900, and the Native Land Act 1909. In addition to being a champion for Maori rights, Ngata remained loyal to the British Crown, and when World War 1 erupted, he assembled a Maori battalion.

Te Rangi Hiroa, also referred to as Peter Buck

Similarly to Ngata, Peter Buck was born in 1877 with both Maori and Pakeha ancestry; however, it is said that his upbringing heavily favoured his Pakeha side, with the exception of some language and legends lessons from relatives. Buck was exceptional at school and studied to become a doctor. In 1905, he was inspired to dedicate his career to providing health services and sanitation to Maori communities. He liaised between primarily Pakeha medial professionals and Maori leaders to take precautions against the spread of infectious disease. His time in parliament was dedicated to Health legislation, particularly in Maori tribes.

In 1875, Maui Pomare was born to a family of strong Maori leaders. For example, his grandmother was one of a handful of women to sign the Treaty of Waitangi. On his father’s deathbed, he recommended Pomare go to Pakeha school and relay important lessons to their tribe. One such lesson was that of hygiene to prevent the spread of disease. Pomare went on to study medicine in America, for which he raised the funds himself. He returned to New Zealand and lobbied for health reform, which was readily adopted due to scares over the bubonic plague, which had already hit Australia. In the 1920s, he was elected to parliament, where he proposed a number of developments and reforms, not only to health and sanitation, but also to land ownership and Maori representation.

Some claimed that the Party members were ‘westernised’ and were criticised for their alliance with Prime Minister John Seddon (Chambers 2018, p. 196). However, it is because of this alliance that each Party member later became members of parliament and worked to benefit the Maori communities. Despite their alliance with Seddon’s Liberals, who were keen on selling Maori land, the members of the Young Maori Party lobbied for its protection. Their presence in parliament was also crucial as a symbol for equality between Maori and non-Maori peoples as citizens of a modern New Zealand (Chambers 2018, p. 196). Their representation in parliament was an important step for the advancement of attitudes and culture in New Zealand society.

Today, the Maori people make up just 14% of the population (New Zealand Tourism). Yet, the preservation of the Maori culture remains. The Treaty’s framework has been incorporated into many of New Zealand’s subsequent acts and laws that have followed and are maintained accordingly. There are designated seats for Maori representatives in government and many also are elected to general seats, and the Maori language of Te Reo is one of the country’s official language.

Social Changes

New Zealand has long been progressive and inclusive when it comes to representation and social welfare. The Liberal party under Richard Seddon, provided the foundation for democratic progress. It was voted into power after a long time of union strikes and class struggles. Its economic and social reforms were welcomed by the vast majority of the population, both in urban and rural areas and laid the foundation for government that listens to its people. It was first John Ballance who was elected in 1891, but he was quickly succeeded by Richard Seddon, nicknamed ‘King Dick’, in 1893. Despite his five consecutive successful elections, his critics argued he ‘meddled’ in all areas of government (McLean 2017). His parliament’s established important improvements to citizens’ quality of life in all areas to strive for total well-being. Seddon was also exceptionally nationalistic as he opposed joining the Australian Federation forming in 1900. Many Australians at the time were under the assumption that the New Zealand would be easily persuaded to join the the federation, there were plenty of cultural differences and economic independence that distinguished New Zealand. In fact, the national sentiment was that New Zealanders were as much British as Scots or Welsh (Chambers 2018, p. 197), as opposed to being more closely tied to Australians. Additionally, Seddon had ambitions for creating his own South Pacific Empire and appealed to the Colonial Office to allow New Zealand leadership over the Cook islands, Niue, Fiji, and Tonga, the first two of which were granted in 1901.

Suffragette movements had been occurring for several decades and they had won the right to go to university (from the time institutions were built), own property (1884), and vote in local elections in 1875 (Chambers 2018, p. 193). And within the first year of Seddon’s election, women in New Zealand were the first in the world to get full voting rights (New Zealand Now). In fact, the women’s movements in New Zealand were so successful that many suffragettes travelled to Britain and America to assist movements over there. A few decades thereafter, New Zealand elected its first female MP, Elizabeth McCombs, in 1933; and, of course, this tradition of women in power has continued to present day with current Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. Among these egalitarian foundations, the Liberal Party also implemented a vast number of revolutionary welfare programs. For example, it was the first country to provide state pensions and housing to workers (New Zealand Now), in 1898.

Seddon’s death in 1906 marked a shift for the Liberal Party. Despite claiming independent dominion status in 1907, it was only a symbolic name change, and the people and government had growing tensions. The Liberals that took up leadership after Seddon’s death no longer supported working-class farmers, which provoked an unprecedented number of union formations and strikes. John Chambers indicates the number of trade unions increased from 1 in 1896 to approximately 122 in 1908 (2018, p. 207). The Liberals’ response to unions was to extend greater penalties for striking and their voter support rapidly declined until they were replaced with the Reform Party in 1912. The Reform Party, led by William Massey, set about improving land ownership and public service appointment, among other reforms until the start of WW1, when priorities shifted.

New Zealand and War

From the time of British colonisation, New Zealand had enthusiastically supported Britain in its war efforts, beginning with the South African ‘Boer’ War in 1899. Several thousand volunteers and horses were sent to South Africa to aid both in fighting and also medical care and teaching. With a high success rate, New Zealand gained a considerable reputation for strong, voluntary troops.

WW1

New Zealand carried on their reputation when word of World War broke out in 1914 and more volunteers in their thousands enlisted. Of the 1.1 million total population of New Zealand, 100,000 troops were sent. It wasn’t until 1916 that conscription was required (Chambers 2018, p. 215). Contingencies of New Zealand troops were sent to Samoa, Gallipoli, and Passchendaele. They quickly found victory in Samoa, where they took down a German wireless station, marking the first allied victory of the War (Chambers 2018, p.210). It was also the first time that Australian and New Zealand Forces fought together as ANZACs. However, most people attribute the ANZAC name to their collaboration on the protection of the Suez Canal in Gallipoli, April 1915. They held back Turkish advances for the duration of their time on the peninsula, but lost a number of lives doing so. Some 8,141 Australians and approximately 2,700 New Zealanders lost their lives in this battle (Chambers 2018, p. 211). Of this 2,700 about 50 were Maori troops. In spite of mixed responses from both the Maori and ‘Pakeha’ people about Maori fighting in WW1, several Maori volunteered and it was at the battle of Gallipoli that the Maori were accepted and respected by Pakeha and British troops.

The troops sent to Passchendaele were most gravely affected. Recognised as one of the worst days in New Zealand history, there were nearly 3,500 casualties in a matter of a few hours, and it was the first and only time that a NZ division were completely unsuccessful in fulfilling their assignment (Chambers 2018, p. 215). Even still, New Zealand is remembered for their valiant war time efforts. Over the course of WW1, New Zealand suffered with 41, 262 wounded and 16,317 deaths. This represented one third of the eligible male population of the time (Chambers 2018, p. 209). With the end of WW1 came security for New Zealand’s borders, further independence from Britain, and a mounting nationalism.

Inter-war Period

The ‘roaring’ twenties were just a soft purr in New Zealand. While the country enjoyed the new delights of music and innovation, it also suffered from a rapid economic decline as the British were no longer buying their sheep produce in bulk for the Army (Chambers 2018, p. 217). Its economy was strong during the war and farmers, which made up much of the population, were selling their produce at a very good price. In the 1930s, the great depression catapulted unemployment in New Zealand, which was exacerbated by the Hawkes Bay earthquake and fires in 1931. By 1933, unemployment reached 15% (Chambers 2018, p. 222). To curb the economic recession and high unemployment rates, the government invested in public works and hired workers to improve roads and parks. One such example was to dig the Homer Tunnel, one of New Zealand’s top tourist sites. Initially, five men were sent with pickaxes to carve out the 1.2 km tunnel in 1935.

The New Zealand government turned toward a welfare state from this point forward as, in addition to the investment in public works, it nationalised the bank, protected dairy farmers’ income, introduced a 40-hour working week, and implemented a number of hydro-electric projects (Chambers 2018, p. 225). These were consolidated in the Social Security Act of 1938, which would “protect New Zealanders from the cradle to the grave” (NZ Ministry for Culture and Heritage 2017). This has been the basis for welfare legislation since policy has continued to work toward the betterment of New Zealand society.

WW2

Despite a growing sense of pacifism as a result of the human loses of WW1, again New Zealanders were called to arms. This time, they declared war on Germany themselves, instead of just representing an extension of the British Empire (NZ Ministry of Culture and Heritage 2012). A major factor in doing so was New Zealand’s strong belief in upholding democracy around the world, when totalitarianism seemed to be ceaselessly increasing (Chambers 2018, p. 227). Nationalism and democratic values were very strong in New Zealanders at the time. New Zealand had very close involvement with diplomatic relations and the creation of an international security scheme, a purpose served by the establishment of the United Nations Organisation in 1945 (NZ Ministry for Culture and Heritage 2017). Approximately 140,000 New Zealanders, including 16,000 Maori, enlisted and fought bravely. A moderate proportion of them, 10,950, made incredible efforts in air brigades. New Zealand became a defacto American base after the attacks on Pearl Harbour, in a measure of protection against the pressures of the Japanese control throughout South East Asia and the Pacific. Additionally, New Zealand assisted with Japan’s occupation after the end of the war. In post-war analysis, it was estimated that New Zealand lost the greatest proportion of citizens in the Commonwealth at a rate of 6,684 per 1,000,000 people (NZ Ministry for Culture and Heritage 2017). Still, the victory of WW2 meant that widespread democracy was upheld and further unified New Zealand.

It is because of these foundations that New Zealand is widely regarded as one of the most democratic nations in the world. Thanks to the values introduced by the Maori peoples and the partnership established with the British colonisers in 1840, creating an equal and just society has been relatively straight forward. Their passion fight for democracy was brought to the world stage during their involvement in both world war one and two, and continues to this day.

If you want to know more about touring New Zealand, please explore our New Zealand country page which contains important tips and information about touring the country.

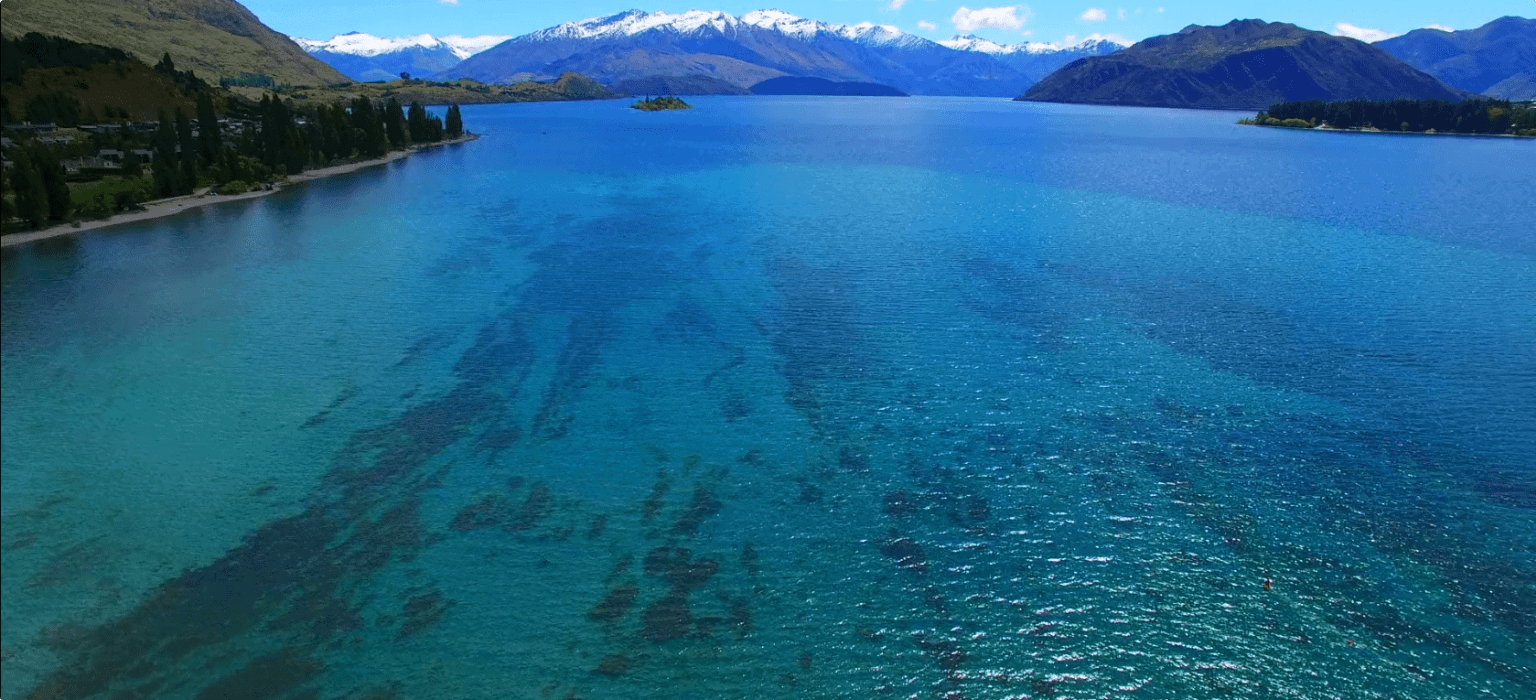

Odyssey Traveller also has an 11-day New Zealand Tour. This tour is a small group educational program tracking the history of the Maori people pre- and post-European settlement. It will also provide first had experience with the geologic gems that New Zealand has to offer. Take in the stunning vistas and interesting stories with other mature travellers. Our small-group approach promises focused attention and camaraderie. Click through the link to see the itinerary and sign up!

About Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. We specialise in educational small group tours for seniors, typically groups between six to 15 people from Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada and Britain. Odyssey Traveller has been offering this style of adventure and educational programs since 1983.

We are also pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey Traveller has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey Traveller achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, do visit and explore our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

Articles about New Zealand published by Odyssey Traveller:

- Creating New Zealand: Transformations in the Early Years of the Colony

- Questions about New Zealand

- Foundations for democracy in New Zealand: 900s – 1945

- Definitive Guide to Auckland, New Zealand

- Wellington

- Auckland

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.