Roman Roads in Britain: The Definitive Guide

Roman Roads in Britain Roads were crucial in the Roman Empire: they facilitated the speedy deployment of troops and the free movement of supplies. Later, when Roman towns began growing into urban centres, the roads…

16 Aug 19 · 7 mins read

Roman Roads in Britain

Roads were crucial in the Roman Empire: they facilitated the speedy deployment of troops and the free movement of supplies. Later, when Roman towns began growing into urban centres, the roads helped in trade and in the daily commute of civilians. The roads also helped unify the vast empire, covering nations of different languages and cultures, into a single institution. In this article, we will look at the roads the Romans built in Britain beginning in 43 AD, and what happened to this network after they left more than 350 years later.

Roman Britain

According to Hugh Davies in Roman Roads in Britain (Shire Archaeology, 2008), the Romans began building a network of roads in Britain “almost as soon as they arrived” (p. 6).

What we know about Roman roads are based on modern archaeological evidence and investigation, as there are few surviving documents about the Romans’ engineering feats.

The Romans invaded Britain–then referred to as Britannia–in 43 AD, and would rule the island as a province of the empire for nearly four centuries.

In Britain, the roads were built the same way they were built in other areas of the empire: in the form of an embankment, and as straight as they could manage it.

Building the Roads

Just two years before the invasion, Caligula, who had drained Rome’s coffers on expensive projects and planned to appoint his beloved horse as consul, was assassinated by the Praetorian Guards.

Britain was an exotic and mysterious place in the Roman imagination, according to the BBC’s Dr Neil Faulkner, and Caligula’s successor, the unpopular Claudius, turned to this mysterious place to prove his military might and get the Senators on his side.

The Roman army sent to Britain was composed of 40,000 professional soldiers and began the invasion with a landing at Richborough in Kent. (Archaeologists still debate whether they also landed in Chichester in Sussex, or if they landed in Chichester first.)

The Catuvellauni was the dominant tribe in Britain at the time, controlling what is now Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and southern Cambridgeshire, and probably Buckinghamshire and parts of Oxfordshire as well. They may have been the same tribe that faced Julius Caesar in 54 BC, before he was called away from Britain to Gaul to deal with the Gallic Wars.

In 43 AD, the Roman army anticipated opposition from the tribe, who were based in their capital, Colchester. The Romans called the tribe’s capital Camulodunum, the “Fortress of the War God Camulos”. Camulos was a Celtic god that the Romans equated with their war god, Mars.

To get to Colchester from where they were beached at Richborough, the Roman troops had to move up the Thames, establish a crossing, and turn north-east (Davies, 2008, p. 11).

Watling Street

This meant they had to build roads, and the road they built to reach the Thames is today known as Watling Street.

It was one of the greatest roads in Britain in Roman and post-Roman times, running from Dover to London, and northwest via St. Albans (Verulamium) to Wroxeter. Watling Street would later have a monument, large enough to be visible to those approaching from the sea, and a fort (p. 11) .

The tribes had settled and lived in Britain for centuries, but the existing paths they used did not suit the Roman army’s needs. The Romans needed roads that were still passable in bad weather and strong enough to withstand wagon wheels even when it rained. Roman surveyors and engineers built roads higher than surrounding land, inclined slightly from the centre to allow rainwater to flow into drainage ditches on either side.

The raised mound was called the agger and was covered with metalling, a hardy layer to protect the ground underneath. This technique is still used in road-making today. While nowadays we would be using concrete, the Roman engineers made use of available material and layered loose stones or gravel over the agger. The roads were regularly maintained by replacing the metalling to guard against wear and tear.

To fit two-wheeled vehicles, the roads were built to be at least 3 metres (9 1/2 feet) wide; often, they were wider than 10 metres (33 feet). The average width of Watling Street, for example, is 10.1 metres (Davies, 2008, p. 42).

The Romans also set up milestones, inscribed with the name of the emperor (p. 30). Unfortunately in Britain, only a small number remain in their original positions, as others have disappeared or were simply discarded.

Designing a Straight Road

To design a straight road, long distances had to be surveyed. Roman surveyors, without the aid of sophisticated equipment such as magnetic compasses, travelled the area on foot, recording every landscape feature–or obstacle–such as rivers, mountains, and forests. They bypassed the obstacles when needed, and figured out the best place to indicate a crossing over a river.

The Romans located their Thames crossing very near where the London Bridge is now located. From here to Colchester or Camulodunum, they built what was named the Great Road, allowing the Roman troops to storm and capture the tribal capital.

Camulodunum became the first capital of Roman Britain and in 49 AD was given the status of colonia. In modern terms, this could be likened to city status. In the Roman Empire, a colonia was a planned settlement where retired soldiers could live as citizens after their discharge from military duty. Camulodunum was the first town in Britain to be elevated to such a status.

The Roman legions and their roads soon fanned out from the capital.

(Almost) All Roads Lead to Londinium

The strategic location of the Thames and the bridge the Romans built there contributed to the establishment and growth of a settlement called Londinium, in present-day London. Rome moved the Britannian capital here from Colchester after the anti-Roman revolt led by Queen Boudica (Battle of Watling Street) in 60 AD.

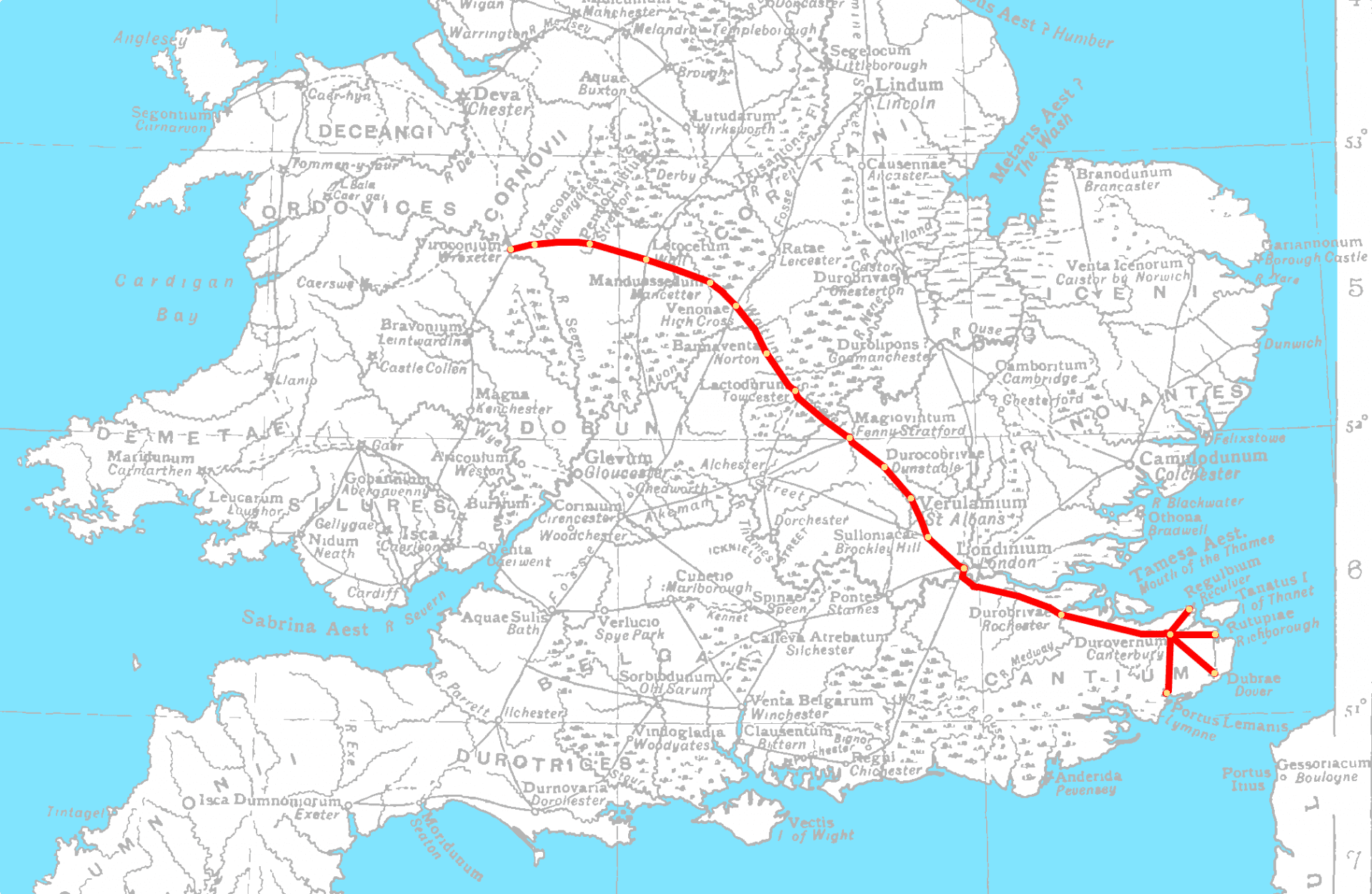

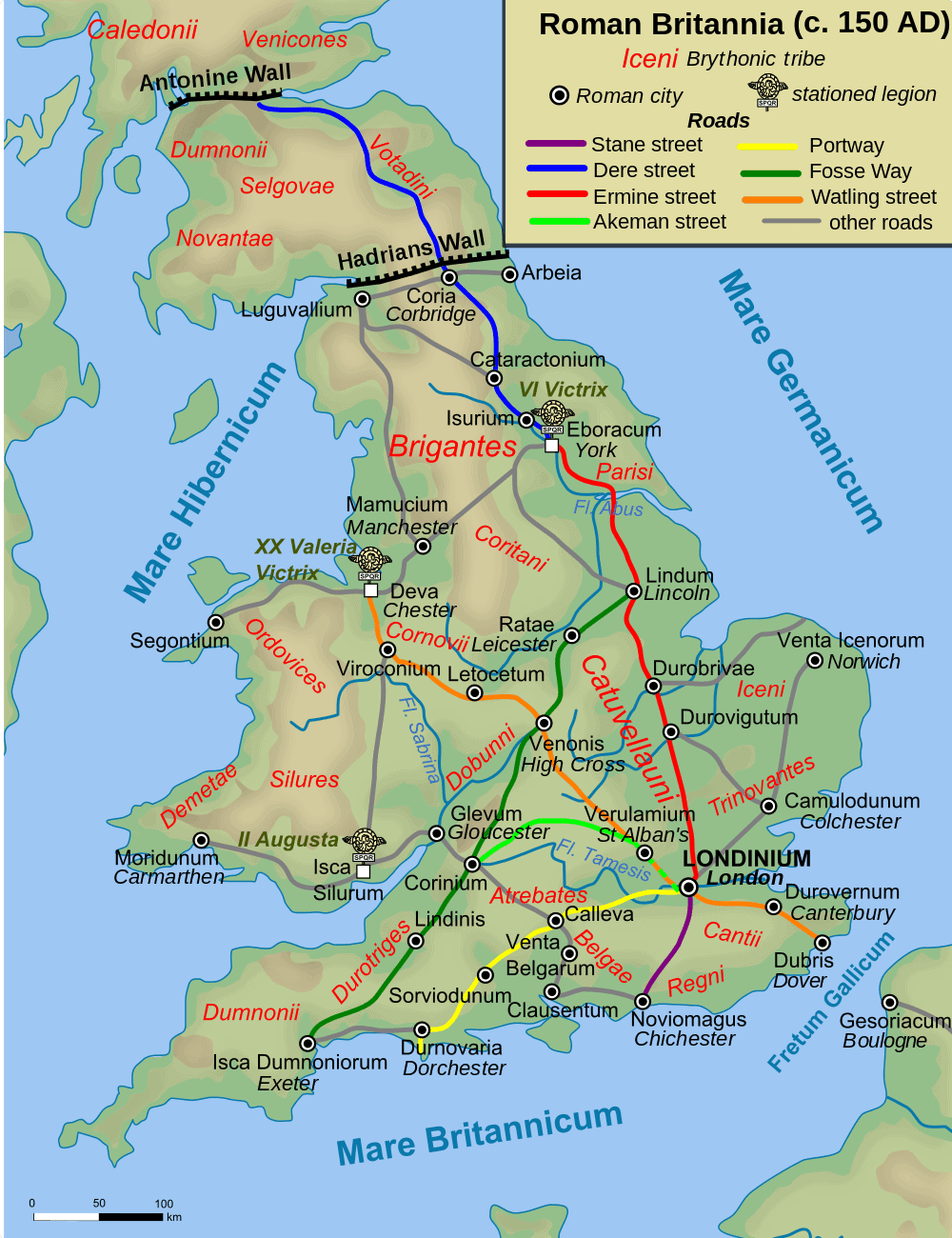

On the map below you can see the roads moving into and out of Londinium, connecting it to other ports and legionary bases. For example, Stane Street connected the southern end of the Thames with Chichester, which had a military port and supply base nearby (Davies, 2008, p. 15); and Ermine Street left the north gate of Londinium onwards to Lincoln, which later became a colonia, and on to York (p. 16).

Davies (2008) says Foss Way (or Fosse Way) is fascinating in that it emanates from neither Londinium nor Colchester, but links the legionary bases in Exeter and Lincoln.

Dere Street and the Roman Walls

Dere Street carried the Roman legions to two important defensive walls in Roman Britain. Hadrian’s Wall was a defensive fortification built around 122 AD, marking the northern limit of Roman Britain. It runs a total of 117.5 kilometres (73 miles) in northern England and was built on the orders of Emperor Hadrian.

North of this wall were the lands of the Picts, a confederation of tribes who unfortunately did not leave written record behind, save for the symbols carved on standing stones which can still be found throughout Scotland. (The tribes have been referred to as Caledonians or Celtic Britons as well.) What we know of them we know from Roman and other historical records, where they were mentioned from around the year 300 to the year 900, after which they might have merged with other cultures.

In 140 AD, Hadrian’s successor, Emperor Antoninus Pius, ordered the building of the Antonine Wall to move the Roman frontier northwards. However, after his death, his successor Marcus Aurelius moved the frontier back to Hadrian’s Wall as it was easier to defend.

The Roads After the Romans Left

Before the Romans abandoned Britannia around 410 AD, they had managed to replace the muddy tracks all over the island with more than 16,000 kilometres of their road network, leaving an incredible mark on Britain’s landscape and its culture.

But resistance persisted throughout Roman rule, with some even instigated by the Romans born in Britannia.

Rome itself was not doing well; in 400 AD, Alaric the Goth invaded the imperial capital, and Roman troops had to be called away to Italy from Britain, leaving the province virtually defenceless against the tribes and other invading forces.

The garrison in Britain responded with a rebellion and proclaimed their own emperor, the general Constantine III. Constantine III would be defeated, but Rome continued pulling away troops stationed in Britain to put out fires in Italy and all corners of the failing empire.

In 410 AD, Emperor Honorius wrote letters to the cities in Britain telling them to “look to their own defences“. The Romans in Britain were effectively on their own.

Before long, the island was resettled by the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, who did not have a stone-building tradition and who reverted Britain to an agrarian way of life. When the Anglo-Saxons did start using stone, they simply reused the bricks left behind by the Romans. One of the earliest stone churches built in England was St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury (597 AD) and was constructed in this manner. (Read more in our previous article about British churches.)

The roads the Romans built were not maintained, and they decayed following the withdrawal of Roman troops.

All is not lost–the original Roman paths survive in long stretches of the following roads (Davies, 2008, p. 54):

- A68 – Dere Street

- A5 – Watling Street

- “old line” of A417 and A419 – Ermin Street

If you want to learn more, we recommend reading Hugh Davies’s Roman Roads in Britain (Shire Archaeology, 2008), and the many resources we’ve linked throughout this piece.

You may also want to join the Romans in Britain tour, organised by Odyssey Traveller. Explore the world of Roman Britain as we trace the visible remains of the Roman occupation. The Romans occupied Britain for more than three centuries and left behind a lasting legacy. Many of their buildings were pulled down and reused but there is still a lot left for us to discover. Join us as we travel in the footsteps of the legions through England and Wales, exploring what remains of their cities, fortresses, villas, bath houses and roads.

All of our tours to the British Isles can be found here. Odyssey Traveller’s tours are all designed for the mature-aged or senior traveller, whether travelling alone or with a partner.