John Eyre Colonial explorer of South Australia

An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 provides articles to support small group escorted tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers of Australia. Eyre explored in the 19th century the Australian bight of South Australia through to Albany as well as NSW. Eyre finished his Administrator career in Jamaica after also being in New Zealand.

Edward John Eyre’s Overlanding Adventures

By Marco Stojanovik

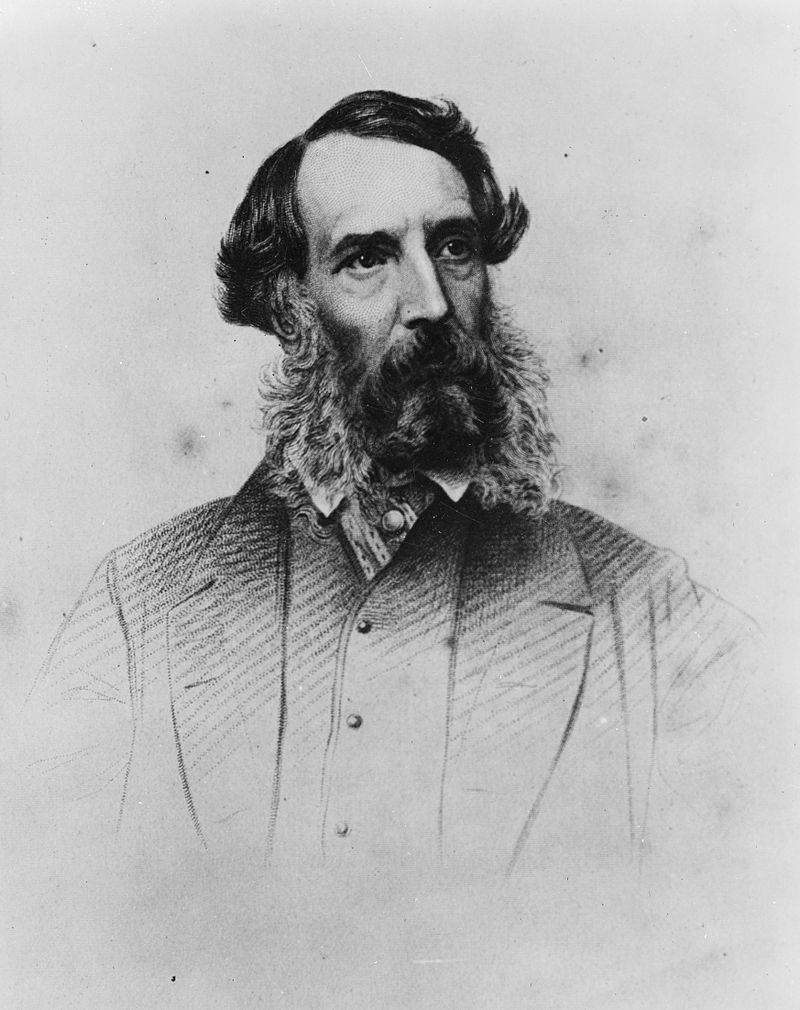

Edward John Eyre, one of Australia’s youngest and most fearless explorers, is immortalized in the names of the South Australian landscape, most notably Lake Eyre and the Eyre Peninsula.

Born in Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, England, on 5 August 1815, he was always a fearless and adventurous child, even then preferring the outdoors to social gatherings. At school he could not sit still, forever yearning for lessons to be over so he could go back outside and explore. Observers considered him an alert youth but fired by impatience and explosive energy. Accordingly, after his schooling he turned down the opportunity for university in search for a more exciting life. Thus, it was at the age of 17, in August 1832, that young Eyre boarded the 352-ton barque Ellen in London and set sail for Sydney town and adventure.

The rest, as they say, is history. Today, the English explorer is considered one of the most accomplished explorers of Australia. He is most famous for his exploration of the interior of central Australia in search of an inland sea, as well as being the first man to cross southern Australia from east to west, travelling along the coast around the Great Australian Bight from Port Lincoln to Albany, via Streaky Bay and the Nullarbor Plain.

However, he first made his name overlanding stock considerable distances across the continent. This article explores three of his most daring and dangerous trips: Sydney to Melbourne; Queanbeyan to Adelaide; and Albany to Perth. It is the first of a two-part series on the life of Edward John Eyre. The second part on Eyre’s expeditions in 1840-41 north to the Flinders Range and then along the Great Australian Bight is available here.

Much of the information presented in this article is drawn from Ivan Rudolph’s Eyre: The Forgotten Explorer.

Overlanding to Melbourne

Eyre arrived in Sydney, in the young British colony of New South Wales, on 28 March 1832 after a voyage of four and a half months and a short stay at Hobart, Tasmania. He spent several months in Sydney but was unable to find work and so moved to the Hunter River district for better prospects. Here, he found employment, gaining experience in sheep and cattle management, and within a month he had bought a flock of 400 sheep.

In 1834, he established his own property in the rugged country of the Molonglo Plains, near Queanbeyan, which he named Woodlands. The following year, he overlanded 3000 sheep from Liverpool Plains to Molonglo, in partnership with wealthy businessmen Robert Campbell. However, he struggled with sheep farming, with many diseased sheep bringing him considerable difficulties.

As such, he disposed of Woodlands in January 1837 and went back to Sydney to try more overlanding. After a successful trip from Sydney to Port Phillip, he set his eyes on Melbourne. With the opportunity to make good profits not likely to last for long – once the track had developed and overlanding became easier, the price for stock in Melbourne would fall – he convinced Charles Campbell (Robert Campbell’s son) to partner with him.

With £500 invested by Robert Campbell and £350 gained from selling most of his possessions, Eyre purchased equipment, 78 cattle, 414 sheep, oxen, and horses. He also hired a dozen men, who would operate in two groups – one to move the sheep and the other to drive the cattle.

Eyre set out for Melbourne on 1 April 1837. The first day was impeded, however, as all the men had gotten roaring drunk the night before and they only managed to travel just three miles in chaotic fashion. The incapacitated men then failed to attend the oxen that night; the oxen strayed with their yokes and boxes on, and these were subsequently stolen.

Eyre had to wait ten days for new ones to be made so the party could set out again. The delay was expensive for Eyre, as he had to maintain provisions and wages for the men while waiting. The potential for profit was slipping away.

Eventually on the way again, Eyre’s first major natural challenge was the wide Murrumbidgee River. After studying it carefully, he decided he could swim the sheep across safely. To his great relief, he was able to do so without losing any. He swiftly crossed back to await the cattle, but they did not arrive when expected.

After four anxious days of waiting, Eyre backtracked until he found the cattle drovers. As the countryside was scrubby, the animals had roamed greater distances than usual at night trying to feed and sixteen had gone missing. Twelve were recovered over the next five days, but the final four were lost forever. Then, as the party moved on a further five went missing.

By chance, Eyre met a neighbouring setter, from whom he was able to purchase five replacement oxen. The following day, he also sighted the last five that had wandered. After two further exhausting days, he finally ran them down and drove them back to the main cattle party, which was by then attempting to cross the Murrumbidgee without him.

Finally, all the cattle were swum across safely. Unfortunately though, that night two oxen wandered back into the river and drowned, and another two became sick and died. Bit by bit, Eyre’s profits were slipping away.

The next target was the Murray River, about 120 miles ahead through unsettled area. Eyre reached it following the tracks the explorer Major Thomas Mitchell had made during his pioneering travels the previous year. The river was wide, expansive, and daunting, but Eyre personally bravely supervised the swimming over of the stock.

Unfortunately, the local oxen Eyre had purchased were wild and hard to control: one broke its neck, another drowned, while others took off. The unruly oxen in turn slowed progress and the men were caught unprepared by the weather. It was so cold that ice an inch thick would form on the water left in buckets and the occasional sleet amounted almost to snow. Most men, however, only wore blue shirts, cabbage-tree hates and long trousers, few even bringing along a coat. A couple of men could not take it and deserted, while two others were seriously insubordinate and had to be handcuffed to be brought back into line.

The party then faced their next major obstacle at the Goulburn River. Here, an overlanding party led by John Coppock was in a dilemma not knowing how to cross such a wide, deep, fast-flowing current. Eyre showed him the way: sheep and cattle were swum over, bags and baggage boated over, and the drays dragged through the river using ropes. After crossing, he leant his boat to the otherwise stranded party and guided them across.

On 2 August, after crossing the Mount Macedon ranges, Eyre finally led his party into the streets of Melbourne. The settlement’s residents excitingly flocked to see the arrival of the valuable stock. The first offers he received, however, were shattering low. Only after a month in Melbourne, did he sell his sheep for the price he was asking.

His cattle, however, would not sell, so he began to devise a daring plan to overland them to the new settlement of Adelaide in Soutfh Australia. News had travelled that beef was so scarce there that the colonists were surviving on kangaroo as their main source of protein. The journey would be dangerous and over mostly untraveled land; nevertheless, Eyre was eager and began preparing for the journey. Just in time, however, he received a suitable offer and so sold his herd in Melbourne.

“Nevertheless, a seed had been sown in Eyre’s mind,” concludes Ivan Rudolph (p. 72). “Overlanding to Adelaide might provide excellent rewards… If he could persuade the Campbells to fund an overlanding drive from Sydney to Adelaide, who could guess what profits might accrue? The market was ripe. The prospect excited him, especially because no one had overlanded stock there previously.”

Overlanding to Adelaide

Robert Campbell shared Eyre’s enthusiasm for an overlanding venture to Adelaide and arranged for Eyre to collect a herd of cattle from his own property, Pialligo Station, near Woodlands. With a herd of 250 head, as well as 65 calves, and a small flock of sheep for meat on the journey, Eyre and his party set out from the station on 20 December 1837.

Eyre was not the only one with the idea of overlanding to Adelaide. Just weeks earlier, Jospeh Hawdon and his deputy leader, Charles Bonney, had set out on their own venture. Aware of this, and desperate to be the first to arrive at Adelaide, Eyre toyed with a dangerous plan: rather than follow the Murray, as he knew Hawdon intended to do, he might cut across more directly to South Australia, starting near Melbourne. Reports of this region was that it was dry and scrubby, but if a way through were possible it would shorten the distance for his stock drive considerably.

Eyre’s party made quick progress on their venture, crossing the Murray successfully and making their way to the Goulburn River. Here, Eyre learnt that Hawdon was following the Goulburn to where it joined the Murray rather than trying to cut across country and shorten the distance. He considered following Hawdon and trying to overtake him, but after reflection decided to execute his earlier plan. Guided by Mitchell’s maps from his exploration of the region in 1836, he would travel westwards of Hawdon until he found a sizeable river, which with luck would provide him a highway to the Murray.

Guiding the cattle and drays safely across the Mount Alexander ranges, Eyre’s party came across vegetation and waterways freshened by the summer rains. This gave Eyre hope that they might proceed westward to the Murray without having to find a river to travel beside. However, upon further reconnaissance, Eyre found insufficient food or water for an overland route directly across the scrublands to the Murray.

Instead, he decided to head for the Yarrrayne River. Eyre was encouraged by Mitchell’s account of the river as a “deep but narrow stream flowing to the westward with a mean depth of nine feet”. The Yarrayne headed more northerly than Eyre expected though and took some days to find, during which there was a lack of water and the faltering cattle threatened to die from dehydration.

Having eventually reached the Yarrayne, Eyre was surprised to find cattle tracks along the riverbank that must have belonged to Hawdon’s herd. He correctly deduced that his competitor had left the Goulburn and had followed the Yarrayne to the Murray instead. There was no point in using this same track now with Hawdon so far ahead of him.

For any chance of arriving in Adelaide first, Eyre would now have to travel south-west to the Wimmera, taking the ultimate risk that the river would in turn lead him to the Murray. To do so he utilised Major Mitchell’s day tracks, which wound towards the Grampians.

Eyre was disappointed upon arrival at the Wimmera: its bed held only intermittent pools and its surrounds were devoid of consistent feed. Conditions were better further along though as eventually the river emptied into a lake. Eyre, the first colonial to see it, named it ‘Lake Hindmarsh’ after the Governor of South Australia, Sir John Hindmarsh.

The water at the lake was ideal for Eyre’s stock, so the droving party rested there while he continued to scout ahead for a route to the Murray. To his alarm, he found only a dry outlet heading towards the river surrounded by scrubby flats stretching away in every direction.

A gruelling journey followed to find the Murray Eyre hoped might intersect the Lindesay River, a tributary the explorer John McDouall Stuart had noticed and named, which entered from the south-west. However, Stuart’s charts were incomplete and after travelling 100 miles Eyre could not find it. With only the same unbroken, almost impenetrable scrub ahead of him, and running out of water, he was forced to turn back.

There was now the dilemma about what to do, as recorded in Eyre‘s journals: “The Wimmera had terminated in Lake Hindmarsh; the Lindesay was not to be found; and although within 200 miles of Adelaide, we had no prospect of reaching it.”

He was to be ruined if his overlanding mission did not succeed. But, back tracking all the way back to the Murray to follow it would take too long. And using Hawdon’s tracks along the Yarrayne to the Murray would be humiliating and still take several months. However, after wrestling with the problem he accepted that this was the only viable option left. So, he turned back to Yarrayne, finally reaching Adelaide on 12 July, more than two months after Hawdon.

Overlanding from Albany to Perth

Following his overlanding venture to Adelaide, Eyre’s attention shifted to exploring the interior of South Australia. But, being away from any commercial enterprise during these explorations, his financial situation slowly deteriorated. A prerequisite for a more ambitious exploration would be to re-establish his financial base. For this, Eyre was determined for his next overlanding venture to be more successful than his last.

His next opportunity came towards the end of 1839 after befriending Lieutenant Alfred Miller Mundy. The two discussed the need to find a fresh market for the bourgeoning stock in South Australia thanks to successful overlandings and new stations being established north of Adelaide. West Australia was the only likely candidate because it still needed sheep and cattle.

Conditions westwards would make overlanding to Perth too risky and shipping all the way there would be too expensive. However, if they could charter a ship at reasonable cost to Albany, on the southern coast of Western Australia, the stock could then be driven overland approximately 230 miles to Perth. A hefty profit could potentially be made given the high prices livestock was fetching in Western Australia.

Governor Gawler of South Australia was pleased with the proposed venture and opportunity to establish a new line of export trade for his struggling colony. He gave Eyre letters of introduction to the Governor of Swan River, and to George Grey (the Government Resident at King George Sound). Grey, in particular, should be able to provide useful information regarding the countryside between Albany and Perth.

Eyre and Mundy accumulated 100 cattle, 1700 sheep and six horses and charted to ships. On 20 January 1840, Eyre loaded 698 of the sheep and two horses aboard the schooner Minerva at Port Adelaide without loss and set sail. Mundy followed aboard the Cleveland with the rest of the stock.

Rudolph (p. 164) describes the journey: “As the voyage progressed, Eyre was astounded by the sight of white waves crushing at the base of the massive cliffs of the Great Australian Bight. The Minerva did not sail close to the coast, but even at a distance Eyre could tell he was seeing one of the wonders of the world… The cliffs erupted almost vertically out of the pounding, restless ocean.”

Lucky the seas and winds were gentle, ideal conditions for the comfort of his sheep and horses. This meant slow sailing, however, with the Minerva arriving at Albany only at the end of February 1840. All the stock were unloaded without any losses, and the success was repeated soon after with the unloading of the Cleveland.

Albany was established as the first settlement in Western Australia in 1827, more than two years before Perth. It was done so to cement Britain’s claims to Western Australia and stave off French interest. In an isolated position and surrounded by indifferent soil, the settlement had remained small.

Eyre and Mundy called upon Captain George Grey upon their arrival to discuss how best to overland the stock from Albany to Perth. Grey’s opinion was that there should be no major obstacle, as small stocks had been brought in by sea and driven from Albany to nearby properties by individuals. However, having only been in Albany a few months, he admitted his knowledge of all the risks was not great and he would make further enquires.

Upon doing so, he learnt of a poisonous plant that grew near the Williams River, around 150 miles from Albany. Before Eyre and Mundy set out, he advised that they be particularly careful to monitor what the sheep were feeding on when approaching that district.

Taking this new information onboard, the overlanders, along with the help of a local Aboriginal companion Wylie, left Albany in early March 1840. The venture started well, easily following the tracks of previous stock and that of the mailman who operated between Albany and Kojonup.

While approaching Kojonup, however, disaster struck. Some sheep suddenly began to behave bizarrely, running erratically some distance away and then back to the flock. They were then generally seized with a violent trembling, dropped down enduring extremely suffering, and died in violent contortions.

Eyre suspecting poisoning to be the cause, decided to open up several of the dead sheep and inspect their intestines to find the answer. He incorrectly deduced, however, that the problem was the cumulative effect of dehydrated plant material clogging up the animals’ digestive systems, rather than poisoning.

Having suffered the loss of 58 sheep in one afternoon, and fearing economically crippling losses if the deaths continued, the men decided to stop for a longer period when they came to water that night to help lubricate the sheep’s food. Still the approach was only partially effective, as the next day within a mile and half of setting out, more than 70 had died or were dying.

They decided to leave the dying and hurry along with the rest as quickly as possible to Kojonup. Here bountiful water slowed the fatalities amongst the sheep. The water treatment had fortuitously been appropriate. Although the deaths were actually the result of a naturally occurring toxin in the plants of the Gastrolobium (poison pea) family, the extra water had diluted the toxins and the dose of salts had moved it through the animals’ systems more rapidly.

Eventually, the men reached York, around 60 miles easy of Perth, where they intended to set up a temporary station where prospective buyers could inspect the remaining stock: 60 cows, two Durham bulls, 700 young ewes, 100 fat heathers, and five horses. Property owners around York bought the lot, and although the numbers had been greatly reduced, high prices enabled Eyre and Mundy to make a small profit.

Meanwhile, Eyre had heard of the HMS Beagle’s surveying of Australia’s northern coastline and the discovery of the great northern rivers from 1837, and he began to wonder what rich lands lay behind the South Australian desert that he had seen. Rudolph (p. 164) writes, “Eyre’s fascination was about to lead him in new and dangerous directions.”

Indeed, with the available funds gained from overlanding, Eyre set out in 1841 on his most famous expedition and one of the great treks across the Australian continent, passing from Port Lincoln, South Australia, to Albany, Western Australia through the arid expanses of the Nullarbor Plain. Read about his adventure here in part two of Odyssey Traveller’s series on Edward John Eyre.

Edward John Eyre Inspired Tours in Australia

Odyssey Traveller follows Eyre’s overlanding paths in a number of our Australian tours.

In particular you may be interested in our tours to the Murray River, the path followed by Eyre in his overlanding from Melbourne to Adelaide. During our Tour of Australian Southern States we round the southern edges of the Murray Darling basin and up to the upper southern part of this complex river basin north of Mildura. We start and end in Adelaide, stopping in Broken Hill, Mungo National Park and other significant locations.

Meanwhile, during our Small Group tour of Victoria, we take a circular route north from Melbourne through Ballarat and Castlemaine as far north as the Murray River, before turning east to Beechworth and then back south again through Benalla and the Yarra Valley, and then, back to Melbourne.

Eyre’s path through Western Australia is also visited on our Wildflower Walking Tour of Western Australia, devoted to south-west Australia‘s extraordinary biodiversity, as we travel from Albany to Perth.

You may also be interested in our Adelaide city and surrounds tour, which takes in many of South Australia‘s premier attractions. We make a day trip to the remarkable rocks of Kangaroo Island and enjoy gourmet food and a wine tour among the rolling hills of the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale wine regions. We also make a day tour cruise down the Murray River, and explore Arts and Crafts mansions in the Adelaide Hills.

Articles about Australia published by Odyssey Traveller:

- The Kimberley: A Definitive Guide

- Uncovering the Ancient History of Aboriginal Australia

- Aboriginal Land Use in the Mallee

- Understanding Aboriginal Aquaculture

- Mallee and Mulga: Two Iconic and Typically Inland Australian Plant Communities (By Dr. Sandy Scott).

- The Australian Outback: A Definitive Guide

- The Eyre Peninsula: Australia’s Ocean Frontier

- Archaeological mysteries of Australia: How did a 12th century African coin reach Arnhem Land?

- Ancient Aboriginal trade routes of Australia

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to Australia:

- Australian Dictionary of Biography: Edward John Eyre and Wylie

- SA History Hub: Edward John Eyre

- Nullabor Net: Edward John Eyre

- Solo trekker Steve Woore follows runaway teen whalers’ 500km pioneering trek across Eyre Peninsula